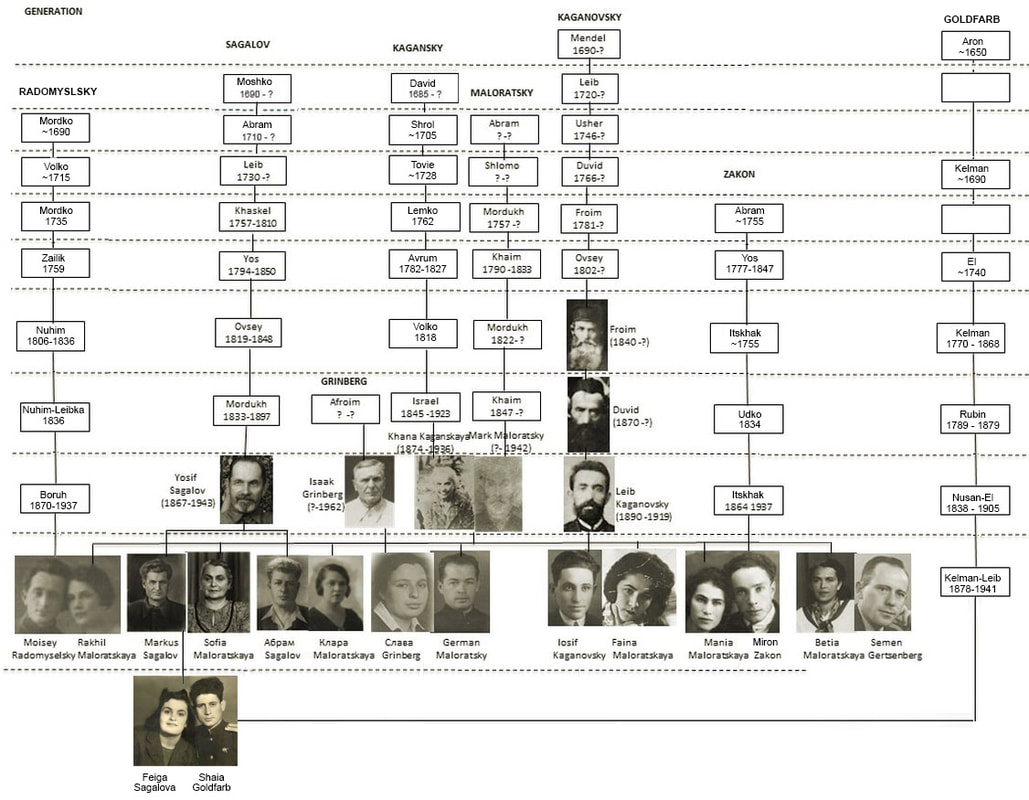

On this website you will discover history of four families - Maloratsky, Kagansky, Sagalov and Goldfarb. It is divided into four chapters.

The first chapter tells the history of the Maloratsky family from 1665.

The second chapter is devoted to the history of the Kagansky family from 1685.

The third chapter is devoted to the history of the Sagalov family since 1620.

The fourth chapter tells the story of the Goldfarb family from 1650.

This work is the continuation of the efforts of our dear relatives Elena and Lev Maloratsky and a fruit of the joint efforts of many dear relatives and friends.

Materials for the Sagalov and Goldfarb families are the main focus of this site, they were collected and summarized by Ilia Goldfarb and his wife Irina. Chapter one - the history of the Maloratsky family was borrowed (copied) from Lev Maloratsky's website http://maloratsky-vinitsky.weebly.com/. Chapter two - the history of the Kagansky family is partially borrowed (copied) from Lev Maloratsky's website http://maloratsky-vinitsky.weebly.com/, and partially supplemented with the help of Arnold Kholodenko with materials from his family archives. Chapter three - the history of the Sagalov family has significantly benefited from the tireless search by Oleg Sagalov in the Kiev Oblastnoy and Historical Archives. We are very grateful to everyone for their help and support.

Thousands of archival documents, photographs and explanations are collected on our website on the basis of which we reconstructed in detail the family trees of the Goldfarb, Sagalov, Maloratsky, Kagansky and Kaganovsky.

Our main sources:

If someone finds any omissions/inaccuracies or would like to make any additions to the history of the families, we will be very grateful and will incorporate this input into our family tree. We hope that stories on this website will be of interest to our descendants and in time they will be able to continue this work.

News, Events & Tips:

This work on our genealogy has inspired Ilia Goldfarb to create a new series of works called "The Jewish Zodiac."

(Learn more)

The first chapter tells the history of the Maloratsky family from 1665.

The second chapter is devoted to the history of the Kagansky family from 1685.

The third chapter is devoted to the history of the Sagalov family since 1620.

The fourth chapter tells the story of the Goldfarb family from 1650.

This work is the continuation of the efforts of our dear relatives Elena and Lev Maloratsky and a fruit of the joint efforts of many dear relatives and friends.

Materials for the Sagalov and Goldfarb families are the main focus of this site, they were collected and summarized by Ilia Goldfarb and his wife Irina. Chapter one - the history of the Maloratsky family was borrowed (copied) from Lev Maloratsky's website http://maloratsky-vinitsky.weebly.com/. Chapter two - the history of the Kagansky family is partially borrowed (copied) from Lev Maloratsky's website http://maloratsky-vinitsky.weebly.com/, and partially supplemented with the help of Arnold Kholodenko with materials from his family archives. Chapter three - the history of the Sagalov family has significantly benefited from the tireless search by Oleg Sagalov in the Kiev Oblastnoy and Historical Archives. We are very grateful to everyone for their help and support.

Thousands of archival documents, photographs and explanations are collected on our website on the basis of which we reconstructed in detail the family trees of the Goldfarb, Sagalov, Maloratsky, Kagansky and Kaganovsky.

Our main sources:

- Funds of the State Archives of Ukraine

- Funds of the State Archives of Poland

https://szukajwarchiwach.pl/ - “Jewish Records Indexing - Poland“

https://jri-poland.org/ - Website Jewish place (Єврейське містечко) of the genealogist Alex Krakowski.

- https://uk.wikisource.org/wiki/%D0%90%D1%80%D1%85%D1%96%D0%B2%D0%B8/%D1%94%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B9%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B5_%D0%BC%D1%96%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%87%D0%BA%D0%BE?fbclid=IwAR1jJD42K7rXYrleD6x7KBy3BvbpisMFU50WasxQMU7Wq7-jpM_hTk8fa2Y

- Jewish genealogy in Ukraine by genealogist Nadia Lipes.

http://jewua.info/ - The All Galitcia Database

https://search.geshergalicia.org/

If someone finds any omissions/inaccuracies or would like to make any additions to the history of the families, we will be very grateful and will incorporate this input into our family tree. We hope that stories on this website will be of interest to our descendants and in time they will be able to continue this work.

News, Events & Tips:

- How to find a Family nest for Jews with surnames from Austrian Galicia?

- Was it possible to assign unique surnames to all the Jews of Galicia in 1787?

This work on our genealogy has inspired Ilia Goldfarb to create a new series of works called "The Jewish Zodiac."

(Learn more)

Ilia Goldfarb's studio wall.

- Lev Maloratsky and Ilia Goldfarb summarized our tree.

News, Events & Tips:

A list of descriptions of cities and towns (shtetl) where our relatives lived.

When we were working on a description of the Polish city of Lublin, I came across an amazing website of the Center "Grodzinskie Vorota - NN Theatre" - a cultural institution of local government based in Lublin. It works to preserve cultural heritage and education.

They created a walk through virtual model of the Lublin Jewish quarter. At the same time, the Polish Archives of Lublin contain detailed birth, death and marriage records from Lublin synagogues with street numbers of houses where our relatives lived. By combining these two sources, one can imagine how his relatives lived.

I thought of the ways that it would be possible to repeat this experience for other cities and towns where my relatives lived, and came up with the following presentation model. We think it may help better imagine the life of our relatives in this city or town.

- Provide a history of the Jews in this city or town.

- Provide a detailed map of the 19th or early 20th century for this city or town, attach photographs of that time and, if possible, indicate the places on the map where these photographs were taken.

- Provide as many old photos as possible to visualize the life at that time.

- Provide photographs of the synagogues of this city or town, with a detailed description of them.

- Provide photographs of the Jewish cemetery in this city or town, with a detailed description.

- Attach photographs related to the Holocaust for this city or town, with a detailed description.

Akkerman (Bessarabia)

Alexandreni (Bessarabia)

Annopol (Ukraine),

Bendery (Bessarabia)

Brusilov (Ukraine),

Bohuslav (Ukraine),

Belogorodka (Ukraine),

Chernyakhov (Ukraine),

Dubienka (Poland),

Fastov (Ukraine),

Korostyshev (Ukraine),

Katerinovka (Ukraine),

Khabno (Ukraine),

Kremenets (Ukraine),

Klimontow (Poland),

Kock (Poland),

Jonava (Lithuania),

Lemberg (Ukraine),

Lublin (Poland),

Lomazy (Poland),

Malin (Ukraine),

Mordy (Poland),

Opatow (Poland),

Piaski (Poland),

Pochaev (Ukraine),

Przemysl (Poland),

Radomysl (Ukraine),

Rzhishchev (Ukraine),

Radivilov (Ukraine),

Slutsk (Belarus),

Shumsk (Ukraine),

Staszow (Poland),

Tarnow (Poland),

Vishgorodok (Ukraine),

Vyshnivets (Ukraine),

Warsaw (Poland),

Yampol (Ukraine),

Zhytomyr (Ukraine),

Zwolen (Poland).

Alexandreni (Bessarabia)

Annopol (Ukraine),

Bendery (Bessarabia)

Brusilov (Ukraine),

Bohuslav (Ukraine),

Belogorodka (Ukraine),

Chernyakhov (Ukraine),

Dubienka (Poland),

Fastov (Ukraine),

Korostyshev (Ukraine),

Katerinovka (Ukraine),

Khabno (Ukraine),

Kremenets (Ukraine),

Klimontow (Poland),

Kock (Poland),

Jonava (Lithuania),

Lemberg (Ukraine),

Lublin (Poland),

Lomazy (Poland),

Malin (Ukraine),

Mordy (Poland),

Opatow (Poland),

Piaski (Poland),

Pochaev (Ukraine),

Przemysl (Poland),

Radomysl (Ukraine),

Rzhishchev (Ukraine),

Radivilov (Ukraine),

Slutsk (Belarus),

Shumsk (Ukraine),

Staszow (Poland),

Tarnow (Poland),

Vishgorodok (Ukraine),

Vyshnivets (Ukraine),

Warsaw (Poland),

Yampol (Ukraine),

Zhytomyr (Ukraine),

Zwolen (Poland).

How to continue the search for ancestors of Jews born before 1795.

Let's start with the history of the Revision tales.

"Tales" in Russia in the XVII - early XIX centuries called official records of explanations or testimonies of various persons. In order to place the burden of maintaining the regular army on taxable estates, Peter the Great, by a decree on November 26, 1718, demanded “Take fairy tales from everyone (give a one-year term), so that the truthful would bring how many people have a man who has sex in his village, announcing to them what he who hides will be given to the one who announces. ”

The audit carried out under Peter became the first. Subsequent audits were held in the following terms: 2nd in 1744-1746; 3rd in 1762–1763; 4th in 1782; 5th in 1794-1795; 6th in 1811; 7th in 1815–1816; 8th in 1833–1834; 9th in 1850; 10th in 1857-1858.

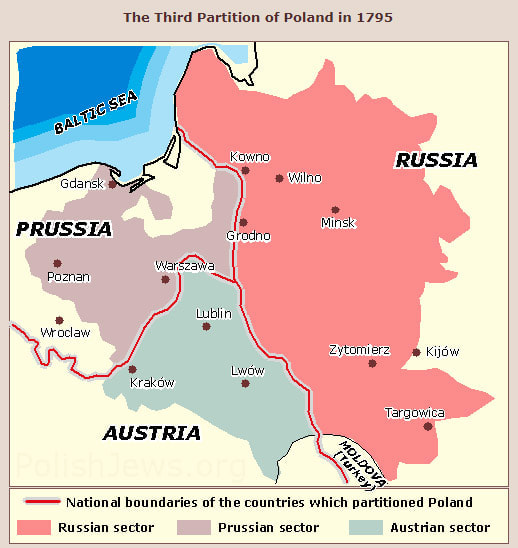

Before the partition of Poland in 1795, there were practically no Jews in Russia. Therefore, in revisions until 1795, Jews did not appear. At that time, Jews lived in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but there were not very many of them there either - Bogdan Khmelnytsky and Koliivshchyna destroyed most of them in the territory that later became Ukraine. That is, by 1795, when this territory was transferred to Russia, Jews lived on it.

Nominal censuses of the Jewish population were made by the Russian authorities with the aim of levying taxes on Jewish kagals, starting in 1795, after the third division of the Commonwealth. Moreover, the common people in Russia at that time did not have surnames, surnames appeared later, after the decree of 1804 *). Therefore, most Jewish family tree in Ukraine begin with the ancestors indicated in this census (1795).

The question is how to continue the search for their ancestors born before 1795?

The following considerations should help answer this question.

Surprisingly, we found a hint in the work of the Ukrainian genealogist Viktor Doletsky, who is the author of an interesting project on creating a genealogical tree of a whole separate village. He came to an interesting generalisation - most of the inhabitants of this village turned out to be second cousins and fourth cousins. At the same time, we know that Christians and Catholics lived where they were born in villages and towns. But the Jews, until 1808, lived on a different principle - they lived in the places of business that they conducted, being, as a rule, shinkars (tavern-keepers) in the villages . At the same time, one small family rented the shinok (tavern). Shinkar, the head of this family, belonged to a certain kagal, usually in a larger town, where the synagogue and the Jewish community functioned. Where can we find relatives of this shinkar? Most likely they belonged to the same community and the same kagal, only lived in neighboring villages, renting other shinoks and wineries.

Common sense dictates that, after 1804, if people living in the same village had the same surnames, then they were probably relatives. This common sense helps in building a family tree for Christians and Catholics. But for the Jews it was more confusing.

In the Russian Empire, the obligation of hereditary surnames was introduced by the corresponding article of the special “Regulation on Jews”, approved by the imperial Decree of December 9, 1804, Article 32 of this Regulation read: “In this census, every Jew must have, or accept his famous hereditary name, or a nickname, which should already be preserved in all acts and records without any change, with the addition to that name given by faith or at birth, this measure is necessary for the better arrangement of their Civil status, for the most convenient protection of their property and for the analysis of litigations between them " In 1808, the Senate re-ordered "all Jews to accept ... certainly a known last name or nickname, if that has not been done yet."

Consider how Jewish surnames were formed. (for more details see the site of Leva Maloratsky https://improbablefamilystories.weebly.com/)

- “Religious” surnames from the words “cohen” and “levy”

Example: KAGANSKIY, SAGALOV

The Coens — the descendants of Aaron’s high priest on the male line — served in the Temple of Jerusalem; the Levites helped them during the services.

Levites (from Hebrew לֵוִי, Levi) - part of the Jews, representatives of the tribe of Levi. In a broad sense, all descendants of Levi are called. - The combination of two German roots

Example: GOLDFARB, HERZENBERG

Vienna officials at the end of the 18th century realized that by combining two German roots, you can get a large number of surnames that had to be assigned for administrative purposes. As the first part, beautifully sounding German words were chosen, meaning precious metals, colors, flowers, sky, sun, etc. As the second part, topographic terms, words from the plant or art world were taken. The result is surnames that sound like typically German. - Occupation

Example: ZALTSMAN, SPIVAK

ZALTSMAN: Translated from Yiddish, this surname means - "a person who deals with salt." As a rule, this meant either production or trade thereof.

SPIVAK: This surname comes from the Polish word "spiewak", which means "singer". It is possible that the ancestor of the bearer of this surname was a cantor in the synagogue. - Connection with the place of residence ("toponymic" surnames)

Example: MALORATSKY, RADOMYSLSKY

Compared with the surnames of other nations, the Jews have an inflated percentage of surnames from the name of the settlements. Almost all cities, towns, villages, towns and villages of the former Pale of Settlement turned out to be the basis of Jewish families.

For example, if you take the name of the Sagalov until 1804 (in 1795), they all lived in different villages and villages located near Fastov. In 1804, the "Regulation on the device of the Jews." From January 1, 1808, "no Jew in any village or village can maintain any rent, shreds, taverns and inns ... and even live in them." And when in 1808 they were relocated to Fastov, they all had the surname Sagalov, since they were all cousins and second cousins and chose the surname according to the religious principle (Levites). But, for example, we did not find such cousins and second cousins at the Maloratsky after moving to Radomysl. This is explained by the simple fact that they lived there, and they had other surnames, such as Radomyslsky or Potievsky.

In this case, the relationship can be confirmed by the following circumstances:

- these villages and villages should be located in the area of the city where these Jews were resettled after 1808.

- it is also possible to confirm the relationship between families with different surnames by the proximity of their entries in the revision tales, they should be recorded nearby.

- an additional argument of family ties of families is that their descendants, according to the Revizki tales of 1795, 1816, 1818, 1834, 1850, have a high percentage of coincidence with the names of the descendants of other surnames.

As a result, when we know the names and patronymics of cousins and second cousins, we can continue the search for the reconstruction of the family tree for several generations of the 18th century.

*) On July 23, 1787, the Austrian Emperor Joseph II passed a law according to which all Jews within the borders of the Habsburg empire were required to have permanent names. In accordance with the law, "surname" was to be completed before January 1, 1788.

Therefore, in 1795, Jews should already have surnames, but surnames in Russia were not used for Jews then. And then, when the decree was issued on assigning surnames to Jews in Russia, the majority chose new surnames, but some retained old surnames, perhaps because they paid bribes to Austrian officials for pleasantly sounding surnames (Goldfarb, Herzenberg).

Why we decided to start searching for the earliest ancestors of the Levites in Belarus and Lithuania.

Most historians believe that the bulk of the Jews, most likely, moved to Belarus in the 12th century from Poland and Lithuania.

Thus, the Jews, once in Belarus, moved further to Ukraine.

After the uprising of B. Khmelnitsky in 1648-1649, the invasion of the Swedes in the late 1650s, the war of 1654-1667. Russia with the Commonwealth, the total extermination of Jews took place in the east of Poland, and 1648–60. were a terrible time for all Polish Jewry. Only those Jews who managed to escape to places not affected by these events survived.

An indirect confirmation of this hypothesis may be the facts of finding identical genealogical lines with surnames originating from the same root in Lithuania and Ukraine.

More recently, while researching the Lithuanian database LitvakSID, I came across information that falls into this category:

In the revision tales of 1816 in the town of Kvedarno (not far from Klaipeda), the family of Segal Mark Yoselevich was recorded. 36 years old according to the revision of 1811 (born 1775), died in 1812. At the same time, the names of Haskel, Itsik, Leiser, Shlomo came across among his close relatives.

This line can be compared with the line of our relatives from Ukraine Mark Yosevich Sagalov (my grandfather), who has all these names along the line of his ancestors.

Checking the revisions on the territory of modern Belarus, according to the revision of 1818, in the town of Novy Dvor there is even a family with the surname Sagolov (Sagalov) Wolf Shmulevich, born in 1738.

In another shtetl Jonava, Kaunas district, I came across several Kagansky families where there are also branches with names similar to ones in Korostyshev. For example, Gershon (1817), Girsh, Israel (1817-1889), Yudko, Khaim, Meer etc.

And when the Jews, moving from Lithuania and Poland in the middle of the 17th century, began to repopulate the territories of Belarus, it happened slowly and carefully. And only after that they began to appear in Ukraine. Thus, we believe that a significant part of the Jews of Ukraine were descendants of Jews from Belarus and Lithuania.

This is a map of the Commonwealth in 1667 after the uprising led by Bogdan Khmelnitsky in 1648-1649.

Overlaid on it:

The red border (approximately, for illustration) is the territory of the uprisings led by Bogdan Khmelnitsky.

The pink border (approximately, for illustration) is the territories annexed by Russia after the third partition of Poland in 1795.

Green border (approximately, for illustration) - the territory of modern Ukraine.

Blue arrows indicate Jewish migration after 1680. It is difficult to say how many migrated from where, but based on the length of the border and the area of the territory (more Jews could live in a larger territory), we can assume that at least half.

Therefore, we decided to start our search for the very first Levites on the territory of Belarus. The earliest mention of a Jew with the name Aron Segal on the territory of Belarus, we found in the town of Gorki, in the Gorki pinkos for 1686.

Overlaid on it:

The red border (approximately, for illustration) is the territory of the uprisings led by Bogdan Khmelnitsky.

The pink border (approximately, for illustration) is the territories annexed by Russia after the third partition of Poland in 1795.

Green border (approximately, for illustration) - the territory of modern Ukraine.

Blue arrows indicate Jewish migration after 1680. It is difficult to say how many migrated from where, but based on the length of the border and the area of the territory (more Jews could live in a larger territory), we can assume that at least half.

Therefore, we decided to start our search for the very first Levites on the territory of Belarus. The earliest mention of a Jew with the name Aron Segal on the territory of Belarus, we found in the town of Gorki, in the Gorki pinkos for 1686.

How did the Jewish Austrian surnames appeared in Ukraine and Poland.

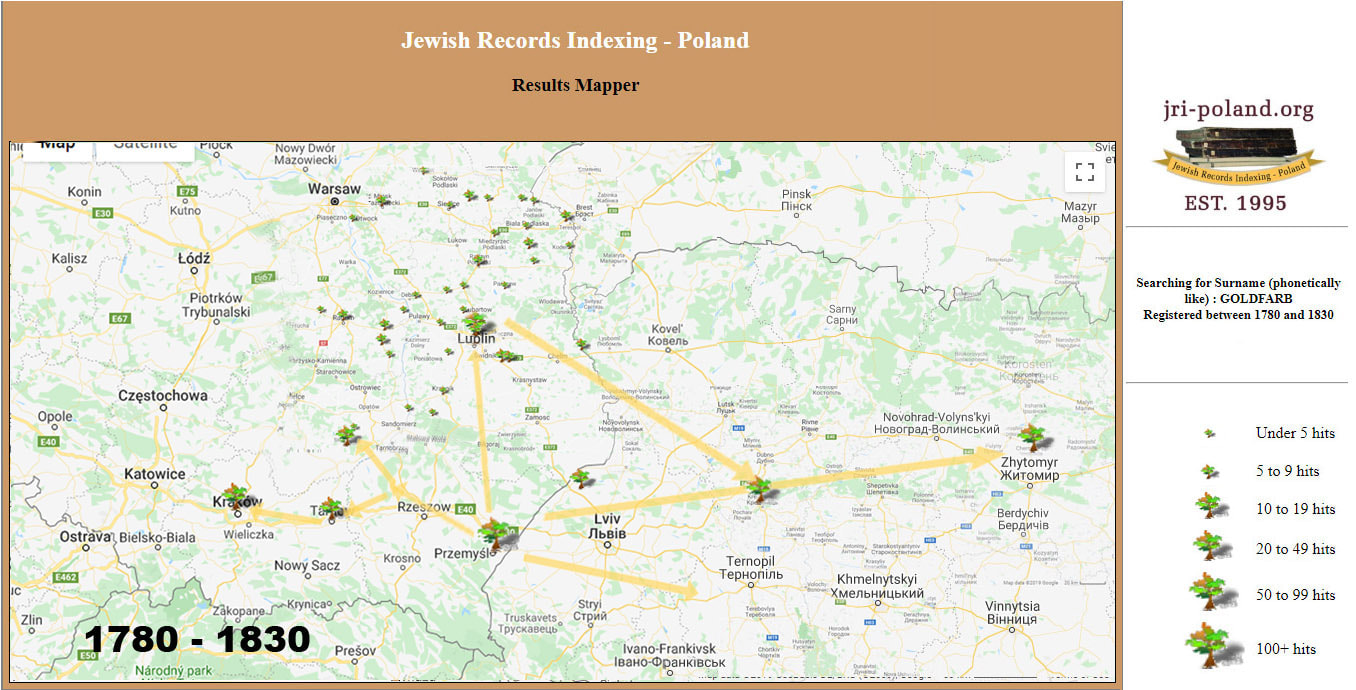

The history of the settlement of Goldfarb in Galicia, Poland and Ukraine.

After a thorough study of historical and archival documents of the late XVIII century, we came to the conclusion that two cities can claim the title of Goldfabs Clan Nest: Lublin and Przemysl. Although there is a high probability that the Goldfarb Tribal Nest was in Przemysl.

In total, until 1795 we found 10 records mentioning the last name Goldfarb in Przemysl and 2 records in Lublin (in the database “Jewish Records Indexing - Poland” (Jewish Records Indexing - Poland).

Until 1815, we found a total of 48 records mentioning the last name Goldfarb. Of these, 34 entries in Przemysl, 9 entries in Lublin, 3 entries near Krakow and 2 in Volyn - Kremenets. That is, we can assume that our ancestors came from Przemysl and Lublin.

In total, until 1795 we found 10 records mentioning the last name Goldfarb in Przemysl and 2 records in Lublin (in the database “Jewish Records Indexing - Poland” (Jewish Records Indexing - Poland).

Until 1815, we found a total of 48 records mentioning the last name Goldfarb. Of these, 34 entries in Przemysl, 9 entries in Lublin, 3 entries near Krakow and 2 in Volyn - Kremenets. That is, we can assume that our ancestors came from Przemysl and Lublin.

|

Map of the first partition of Poland in 1772.

|

After the first partition of Poland in 1772, part of Galicia went to Austria, where Przemysl and Lvov fell, and Lublin, Krakow and Zhytomyr remained Polish.

According to a law issued in 1787 by Emperor Joseph II [5], Jews were required to take a surname, which from that moment became hereditary. In eastern Galicia, where a large part of the Jews of Austria lived, and which was removed from the center and, accordingly, from the control of the capital’s authorities, officials began to abuse the right to appoint surnames at their own discretion: they extorted bribes from the Jews for the right to receive a harmonious surname, and those who refused to pay or did not have the means to do so were assigned surnames with offensive or comic meanings. Most of the newly assigned surnames were derived from the words of the German language, the official language of the empire. |

Some of the surnames taken indicated the occupation, others reflected the nature of the character or appearance of their carriers. However, most of the new surnames were arbitrarily derived from various words of the German language, while many of these surnames were of an “ornamental” nature.

Many new surnames were composed of two German roots - Goldfarb, Weinstein, Goldwasser, etc.

At this time, changes occurred in the organization of the Jewish community and its living conditions. The community was subject to Austrian laws, according to which restrictions were imposed on Jewish trade, as well as on Jewish marriages.

The tax burden during Austrian rule was heavy. The taxes on meat taxed by Jewish trade were as follows: for each kilogram of meat there were 3 cruisers, 2 cruisers for a pigeon, 14 cruisers for a geese, 6 cruisers for a chicken or duckling and 20 cruisers for a swan. Duties were assigned to the candles a piece. And every Jewish family lit two candles every Saturday and holiday.

And probably many Jews were looking for places with more liberal laws that still remained in Poland. This may explain how some Goldfarbs, who only got their surname, decided to move to Poland: to Lublin, Kolbushevo, Staszow, Tarnow, Kremenets and Chernyakhov.

After the second and third partition of Poland, the Goldfarb families from Kremenets and Chernyakhov came to Russia.

Many new surnames were composed of two German roots - Goldfarb, Weinstein, Goldwasser, etc.

At this time, changes occurred in the organization of the Jewish community and its living conditions. The community was subject to Austrian laws, according to which restrictions were imposed on Jewish trade, as well as on Jewish marriages.

The tax burden during Austrian rule was heavy. The taxes on meat taxed by Jewish trade were as follows: for each kilogram of meat there were 3 cruisers, 2 cruisers for a pigeon, 14 cruisers for a geese, 6 cruisers for a chicken or duckling and 20 cruisers for a swan. Duties were assigned to the candles a piece. And every Jewish family lit two candles every Saturday and holiday.

And probably many Jews were looking for places with more liberal laws that still remained in Poland. This may explain how some Goldfarbs, who only got their surname, decided to move to Poland: to Lublin, Kolbushevo, Staszow, Tarnow, Kremenets and Chernyakhov.

After the second and third partition of Poland, the Goldfarb families from Kremenets and Chernyakhov came to Russia.

Goldfarbs moved from Lublin to the territory of the Kremenets region - to Berezetsy

Goldfarbs moved from Przemysl to the territory of the Zhytomyr region - to Chernyakhov.

Goldfarbs moved from Przemysl to the territory of the Ternopil region and further to the territory of the Odessa region.

After the annexation of the new Polish territory, following what they did to the Galician Jews, the Austrian authorities, in the process of secularization, issued a series of decrees that allowed Jews to obtain civil rights. Thus, the Jews were forced to add Polish surnames to their Jewish names, but they were allowed to choose their own surnames, unlike Galicia, where the bureaucracy determined the surnames. Starting from this period, these surnames have been preserved to this day, such as: Tchaikovsky, Lubelsky, Rabinovich, Davidovich, etc. Therefore, it can be assumed that the Goldfarbs recorded in these cities moved there from Galicia (Przemysl).

Goldfarbs moved from Przemysl to the territory of the Zhytomyr region - to Chernyakhov.

Goldfarbs moved from Przemysl to the territory of the Ternopil region and further to the territory of the Odessa region.

After the annexation of the new Polish territory, following what they did to the Galician Jews, the Austrian authorities, in the process of secularization, issued a series of decrees that allowed Jews to obtain civil rights. Thus, the Jews were forced to add Polish surnames to their Jewish names, but they were allowed to choose their own surnames, unlike Galicia, where the bureaucracy determined the surnames. Starting from this period, these surnames have been preserved to this day, such as: Tchaikovsky, Lubelsky, Rabinovich, Davidovich, etc. Therefore, it can be assumed that the Goldfarbs recorded in these cities moved there from Galicia (Przemysl).

Goldfarb settlement map for Galicia, Poland and Ukraine. 1780-1830

How to find a Family nest for Jews with surnames from Austrian Galicia?

Data for statistical analysis are taken from the database "Jewish Records Indexing - Poland" https://jri-poland.org/

Goldberg - ~ 44000

Goldstein - ~ 28000

Greenberg - ~ 22000

Goldman - ~ 20,000

Goldfarb - ~ 10000

Weishtein - ~ 7000

Greenstein - ~ 6000

Goldschmit - ~ 4000

Goldfeld - ~ 1500

Goldblatt - ~ 1500

My assumptions taken as the basis for statistical analysis.

- Surnames in Austrian Galicia began to be assigned around the same time 1777-1778.

- Geneticists say that if a man has many brothers in the family, then he will have more sons, and if there are many sisters, then, accordingly, daughters. Only some men have the sperm that contains an approximately equal ratio of X- and Y-chromosomes, and both boys and girls are born with the same probability. ( rz.com.ua/ru/content/chto-rebenok-nasleduet-tolko-ot-otca-dannye-genetikov )

- One boy (with dominant Y- chromosomes) generated about ~ 10000 records in the Jewish Records Indexing - Poland database. One boy (with equal ratio of X- and Y-chromosomes) generated about ~ 5000 records in the Jewish Records Indexing - Poland database. One boy (with with dominant X- chromosomes) generated about ~ 1000 records in the Jewish Records Indexing - Poland database.

- Some surnames have only a part of the entries taken into account (not all documented or digitized).

- Austrian officials had strict rules for assigning surnames.

This is the picture.

If at the time of assignment of the surname the family had

Goldberg - 7-8 boys (~ 44000)

Goldstein - 5-6 boys (~ 28000)

Greenberg - 4-5 boys (~ 22000)

Goldman - 4 boys (~ 20,000)

Goldfarb - 2-3 boys (~ 10000)

Weishtein - 2 boys (~ 7000)

Greenstein - 1-2 boys (~ 6000)

Goldschmith - 1-2 boys (~ 4000)

Goldfeld - 1 boy, (~ 1500, part of records)

Goldblatt - 1 boy, (~ 1500, part of records)

All these constructions help to conclude that if most of the records in the database "Jewish Indexing Reports - Poland" by surname before 1815-1830 were concentrated in one place (city), then this place was probably the Family nest of this surname.

An Edict of Joseph II Requiring Jews to Adopt Fixed Surnames and German Given Names, Vienna: July 23, 1787.

An Edict of Joseph II Requiring Jews to Adopt Fixed Surnames and German Given Names, Vienna: July 23, 1787.

This raises a rather interesting question: Was it possible to assign unique surnames to all the Jews of Galicia in 1787?

My thoughts on the matter:

In 1772, the Austro-Hungarian Empire annexed the territory of Galicia to its empire.

Galician Jews or Galicians (Yiddish: גאַליציאַנער ) are members of a subgroup of Ashkenazi Jews originating and living in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

One should take into account that at that time Galicia was under the direct rule of Joseph II himself, the Holy Roman Emperor, who personally appointed the governor of this territory. In his imperial decree promulgated on July 23, 1787, he required all Jews to adopt clear surnames and German names, “in order to avoid the disturbances which usually affect certain classes of people in political and judicial proceedings, as well as in their private life, when families have no fixed surnames and individuals have no recognized names.” Although names had to be German, no such condition was made on surnames, unless they were Yiddish names or names of towns. Jews in the empire were required to submit signed applications to local authorities to register their newly chosen names by the end of November 1787 and were obligated to begin using these names by January 1, 1788, or face a fine (or expulsion if the fine could not be paid). Moreover, the district rabbis were obligated to keep all records of births, circumcisions, marriages and deaths in German and using new names. The decree applied to the entire empire, but the present document was aimed specifically at the Jews of Transylvania and Galicia and was signed by the local authorities.

One of the main purposes of this decree was to make Jews useful to the state and was a continuation of the integration of Jews into Lower Austrian society made possible by the 1782 decree, which undoubtedly contributed to economic success.

Giving Jews unique surnames was one of the criteria for achieving their usefulness to the state. Joseph II's social and religious reforms were not so much about creating a just society as about getting the most taxes and the most recruits from his people in the most efficient way possible. In his view, prosperity was only good because it meant more revenue for the state.

At the time Galicia was annexed by Austria (i.e. the Habsburg Monarchy), in 1772 there were between 140,000 and 150,000 Jews living there, which was 5% of the total population. In 1776, for example, there were 144,000 jews.

For our rough calculations we will take the figure of 150,000. Again, if we roughly assume that one family consisted of 6-7 people, we need a total of ~21,000-25000 unique surnames.

Prior to this period, Jewish names usually changed with each generation. For example, if Moses, son of Mendel (Moishe ben Mendel), married Sarah, daughter of Rebekah (Sarah bas Rifke), and had a boy and named him Samuel (Shmuel), that boy would be called Shmuel ben Moishe. If they had a girl and named her Feigele, she would be called Feigele bas Moishe.

Austrian officials, in carrying out the decree of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, to assign surnames to Jews, used the following procedure. Most of the newly assigned surnames were derived from words of German, the official language of the empire. Some of the surnames indicated occupation, others reflected the character or appearance traits of their bearers. However, most of the new surnames were arbitrarily formed from various words of the German language, and many such surnames had an “ornamental” character. Two German words were taken and written down as one surname (Goldberg, Goldfarb, Weishtein).

In this case, we need to figure out how many unique words are needed to create 20,000-25,000 combinations of two words? It's a simple math problem and the answer is approximately 201-225 words.

That is, it is theoretically possible to take about 201 words and form 20,000 surnames with two-word combinations. In practice, they probably could have used even more words (300, not much) to form more pleasant-sounding combinations. This was easily doable.

This number of 25,000 existing surnames is confirmed by the “Dictionary of Jewish surnames of Galicia” by Doctor of Sciences Alexander Beider. Dr. Beider as a leading authority on Eastern European Ashkenazic names. (https://www.avotaynu.com/books/DJSG.htm)

Further evidence that giving Jews unique surnames was one of the criteria was the very procedure of Austrian officials recording a surname made up of two different words in order to produce as many unique surnames as possible.

Everyday scenes of the life of Jews in the second half of the 18th century.

While working on the "Goldfarbs from Warsaw" section, I came across interesting information about Jews in Poland. I have never come across paintings depicting the life of Jews in the years 1760-1790. And in those days an interesting artist Bernardo Bellotto lived in Warsaw, who painted pictures of the streets of Warsaw of that time, where he captured everyday scenes of the life of the Jews of Warsaw. In those days, the Jews did not have artists and nothing of the kind could remain with them.

"The Żelazna Brama square", 1779, Bernardo Bellotto

ŻELAZNA BRAMA SQUARE

From the beginning, life in the neighbourhood revolved around trade. In 1650, when Jan Grzybowski set up the jurydyka (a settlement within the city's limits not subject to its laws but governed by their own rules), called Grzybów, a marketplace was established in the square in front of the city hall, where people traded with wheat and beer. In 1693, the Wielopolski family created Wielopole jurydyka in the same vicinity,which also became very popular with merchants. The market got its name, Żelazna Brama Sqaure, because it was next to the Saski Garden whose entrance was marked by a beautifully ornamented iron gate.

On the painting The Żelazna Brama Square, 1779, by Bernardo Bellotto Canaletto the residents of former Wielopole are portrayed: two Jews are talking, women are hanging the washing, and a goat is playing with a dog. On the left you can see the baroque palace of the Lubomirski family which was bought in 1834 by Abraham Simon Cohen, he turned it into small flats and retail space to rent out. In 1872 a well-known Warsaw cantor, Jakub Leopold Weiss, set up a synagogue in the palace and on the first-floor terrace beautiful wedding ceremonies were held. In the square, in front of the palace, a bazaar and rows of vendor stalls began to expand gradually.

"This square, of quite irregular shape, is limited by the following streets: Zimna, Przechodnia, Ptasia, Żabia, Graniczna, Gnojna and Skórzana. Its limits are built up with large tenement houses. The square is the place of the largest market in the city. It is an oracle which decides on the prices of commodities in all seasons."

Eryk Jachowicz, Ilustrowany przewodnik po Warszawie, 1893.

(Learn more)

From the beginning, life in the neighbourhood revolved around trade. In 1650, when Jan Grzybowski set up the jurydyka (a settlement within the city's limits not subject to its laws but governed by their own rules), called Grzybów, a marketplace was established in the square in front of the city hall, where people traded with wheat and beer. In 1693, the Wielopolski family created Wielopole jurydyka in the same vicinity,which also became very popular with merchants. The market got its name, Żelazna Brama Sqaure, because it was next to the Saski Garden whose entrance was marked by a beautifully ornamented iron gate.

On the painting The Żelazna Brama Square, 1779, by Bernardo Bellotto Canaletto the residents of former Wielopole are portrayed: two Jews are talking, women are hanging the washing, and a goat is playing with a dog. On the left you can see the baroque palace of the Lubomirski family which was bought in 1834 by Abraham Simon Cohen, he turned it into small flats and retail space to rent out. In 1872 a well-known Warsaw cantor, Jakub Leopold Weiss, set up a synagogue in the palace and on the first-floor terrace beautiful wedding ceremonies were held. In the square, in front of the palace, a bazaar and rows of vendor stalls began to expand gradually.

"This square, of quite irregular shape, is limited by the following streets: Zimna, Przechodnia, Ptasia, Żabia, Graniczna, Gnojna and Skórzana. Its limits are built up with large tenement houses. The square is the place of the largest market in the city. It is an oracle which decides on the prices of commodities in all seasons."

Eryk Jachowicz, Ilustrowany przewodnik po Warszawie, 1893.

(Learn more)

Look-alike human pairs

Scientists have found that look-alike are similar to us not only in appearance, but also in DNA.

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(22)01075-0

People with a strong external resemblance turned out to be genetically related. Because of this, they can have the same height, weight, behavior, and even bad habits.

When analyzing the DNA of look-alikes, it turned out that a strong external similarity is associated with genetic characteristics.

“People with very similar faces have common genotypes, although they differ at the level of the epigenome and microbiome,” explained one of the authors of the study, Manel Esteller.

In genealogy, this fact can help with the choice of the tribe of the family tree, which owns a branch of close relatives.

|

It's one of biology's biggest questions: is it nature or nurture that makes us who we are? Now, thanks to twin studies, scientists like Dr. Nancy Segal may just have some answers. By studying identical twins separated at birth scientists can gain unique insight into just how much our genes influence our behaviour, personality and traits. |

|

|

For a long time, scientists believed that it wasn’t possible to alter our genetic code. Now, epigenetics is changing the game.

Epigenetics, the study of the code that controls our DNA, tells us that our lifestyle choices can have a significant impact on our gene expression and our lives. |

|

Why do we need a family tree?

Humans are social animals. From a biological point of view, a social animal is one that cannot survive without the company of its own kind. The family is the smallest but most important primary unit of society, in which people are connected to each other by certain relationships.

Some connections in the family are determined by nature - by our genes, which are passed on from parents to children, and parents received them from their parents, etc. That is, it turns out that each of us has a piece (genes) of our ancestors. At the same time, it has now become known that genes are responsible for a significant part of our behavior, habits, hobbies, and even the choice of profession. When you have the opportunity to learn about the lives of your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc. it helps to better understand yourself and find the right path in life. Plus, you get a sense of belonging and participation in a life that lasts many hundreds of years.

Below are some practically useful examples of this approach.

A Family

Yulia Kravchenko, chapter from the book "Healing Loneliness"

Practice shows that 90% of people hardly remember the names of their great-grandparents, and, alas, they can say little about their life. But ideally, a person should know his ancestors up to the seventh generation! No wonder the word "family" in Russian consists of two components: "Seven" and "I".

The tradition of knowing and honoring one's ancestors was well known to previous generations and completely forgotten in our time. We have lost the understanding of why this is necessary and for what, and therefore we have completely ceased to be interested in our roots. After all, our lives depend on it!

It is not for nothing that the memory of the family is entered into the family tree. The trunk of the tree symbolizes ourselves, the leaves are our children, and the roots are our ancestors. Now imagine that you have grown large and healthy offspring and your tree looks strong and powerful. But you know almost nothing about ancestors and have never been interested. What are the roots of such a tree? Weak, small, lifeless. In the event of a hurricane, they will not be able to keep the tree in the ground, protect it from bad weather. This is exactly what happens in life. If a person is not interested in the past and does not even understand why he needs to know his ancestors, then he loses the help and support of the clan, the power that sometimes saves entire lives!

But just knowing is not enough. If a person in life has developed a bad relationship with his parents, grandparents, it is at this place that the flow of clan energy is blocked. Resentment, anger, hatred not only prevent the nourishment of the power of the family, but also transform this power into a negative and destructive one. Surely you have heard of birth curses? Therefore, it is so important to improve relations with loved ones if they are still alive or forgive them if they have died.

But this is not the only reason why you need to know your ancestors and maintain good relations with them (even if they died, thinking well of them, we establish a birth channel through which they feed us with energy). Seven generations of a person symbolize his seven energy centers - chakras. Each generation shapes certain aspects in our life:

- First generation(s).

- The second generation (parents - 2 people) - form the body, health, transmit family scenarios.

- The third generation (grandparents - 4 people) - are responsible for the intellect, abilities, talents.

- The fourth generation (great-grandparents - 8 people) - keepers of harmony, joy in life and material well-being.

- The fifth generation (parents of great-grandfathers - 16 people) - are responsible for safety in life.

- The sixth generation (grandfathers of great-grandfathers - 32 people) - provide a connection with traditions. The 32 people of the sixth generation symbolize 32 teeth, where each tooth is associated with each ancestor. If you have problem teeth, you should improve relations with your ancestors, pray for them.

- The seventh generation (great-grandfathers of great-grandfathers - 64 people) - are responsible for the country, city, house in which we live. If 64 people are sorted by numbers, then this is what happens: 6+4 = 10 -˃ 1+0 = 1 - First generation again. Thus, the circle of the family of seven generations is closed.

Yulia Kravchenko, chapter from the book "Healing Loneliness"

Source: twiy.ru

What are our children like?

I came across some interesting information about the mission of the clan and its karma (https://www.cluber.com.ua/lifestyle/interesno/2021/09/kto-vy-i-dlya-chego-v-vashem-rodu-missiya-i-karma/), which refers to clan's karma:

“…

The first child in the family is responsible for and closes the gestalts of the family line on the father's side, which gives protection and direction, where to move and what problems to solve.

The second child solves the tasks of the family through the mother's line. Everything unfinished, unfinished by his ancestors will have to be done by him/her. And yes, the help of the family through the mother's line is provided.

The third child "does not belong to anyone". He/she lives on his own, birth problems do not concern him/her, but they are not helped either. He, like an outsider, goes his own way, living in a way that is understandable only to him, he, as it were, creates a new branch of the family.

The fourth child is a repetition of the first.

The fifth is a repetition of the second and so on…”

Geneticists say that maternal genes provide 50% of the child's DNA, the remaining 50% children inherit from the father. But recent research suggests that things are not so simple, that much also depends on the dominance of certain genes. And here the picture can change - for example, 60/40, etc.

After many years of work with our family tree I noticed the following patterns, which seem to be repeated in our family more often than by a statistical accident.

The first child in the family has more similarity (dominant genes?) to the father's side.

The second child in the family has more similarity (dominant genes?) to the mother's side.

The third child is half paternal and half maternal.