CHAPTER 3 SAGALOV

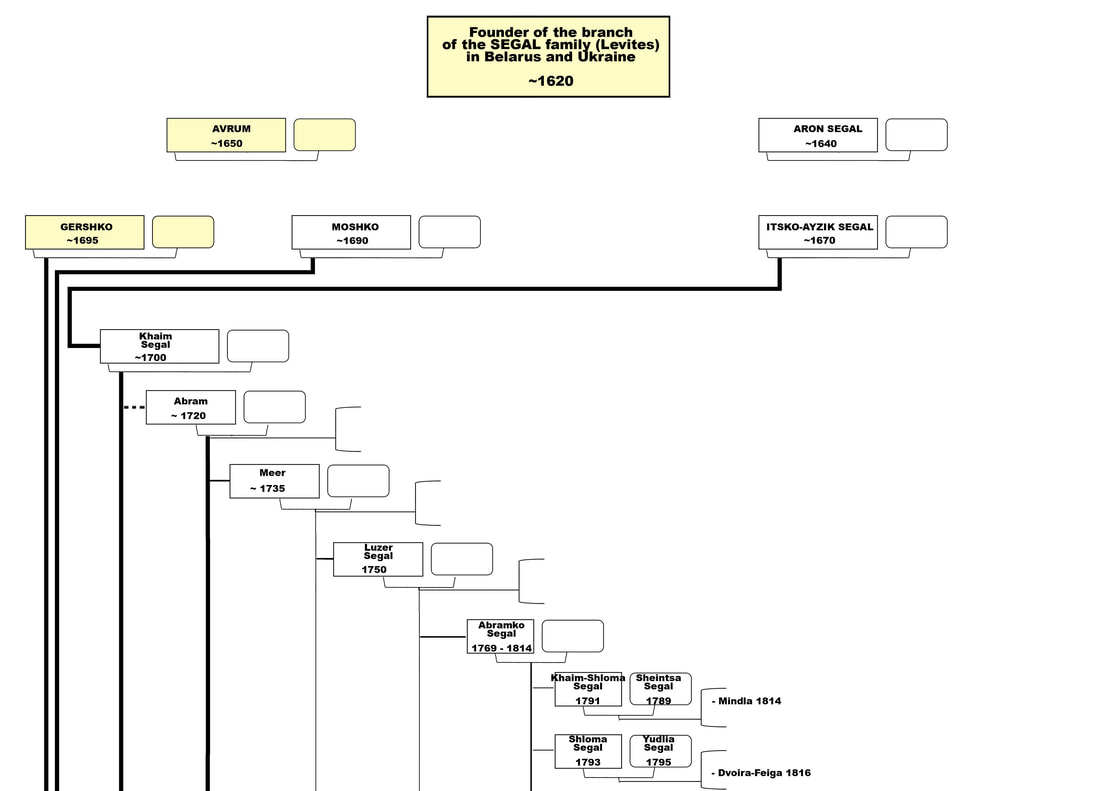

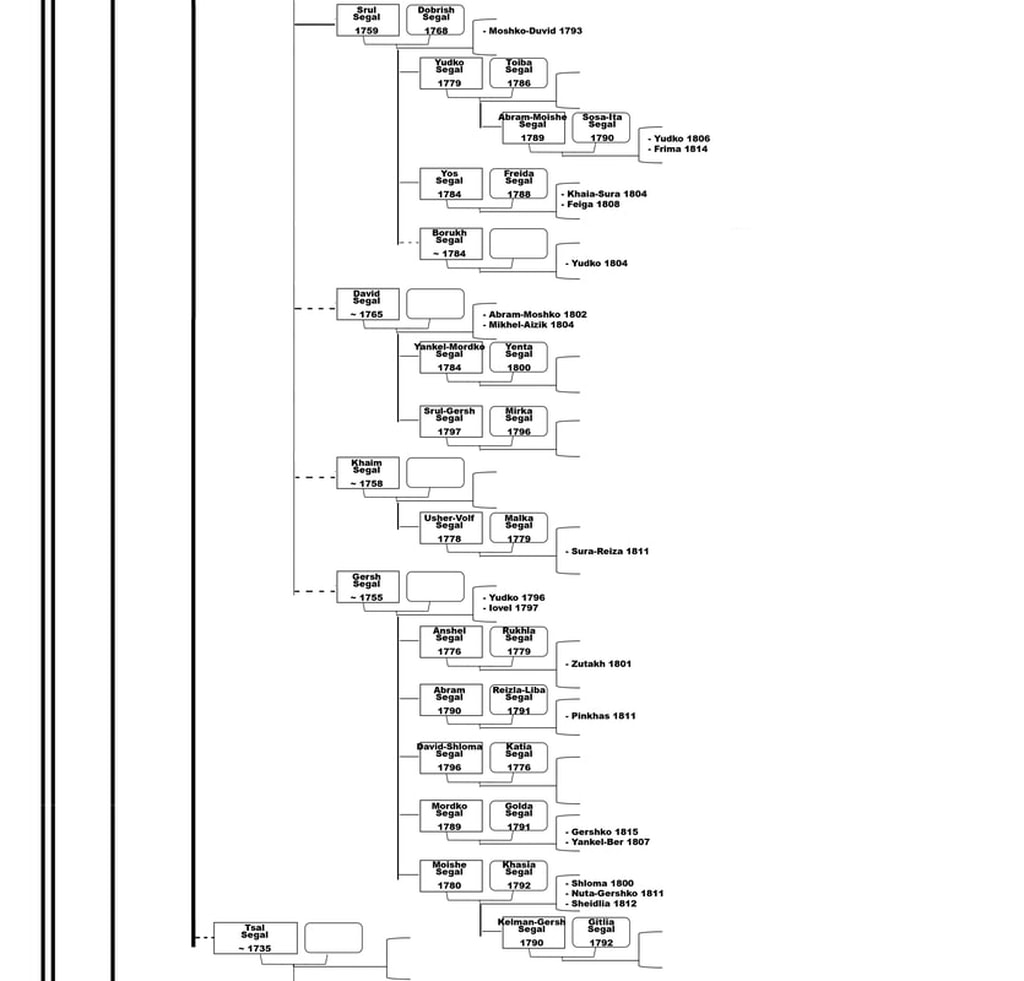

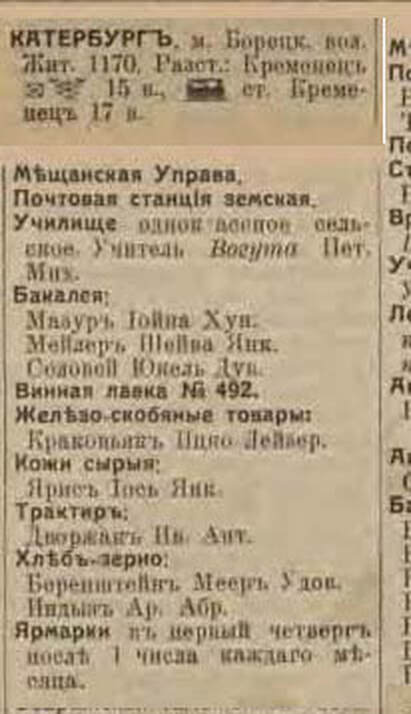

Sagalov family since 1620

Sagalov family since 1620

Content

INTRODUCTION

OUR ANCESTORS UP TO THE 18TH CENTURY

SAGALOV FAMILY IN UKRAINE

DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK SEGAL

KHAIM BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK)

AYZIK SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

ABRAM SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM KATERINOVKA

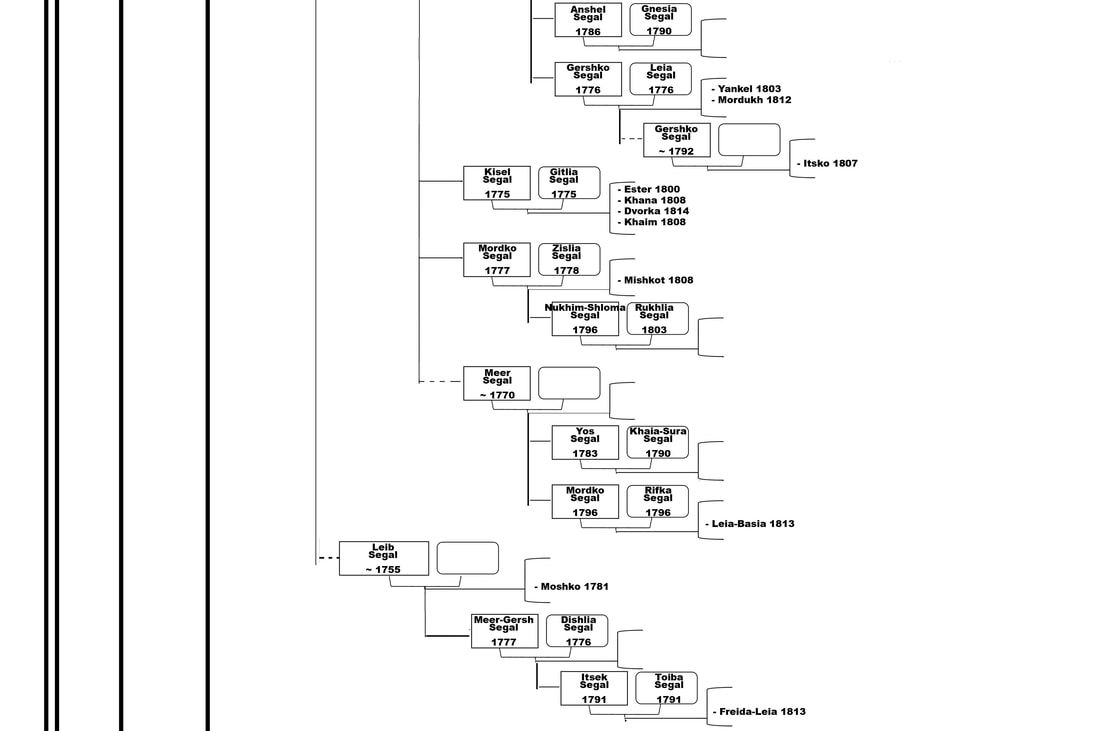

MEER SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

OVSHIA SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM ANNOPOL

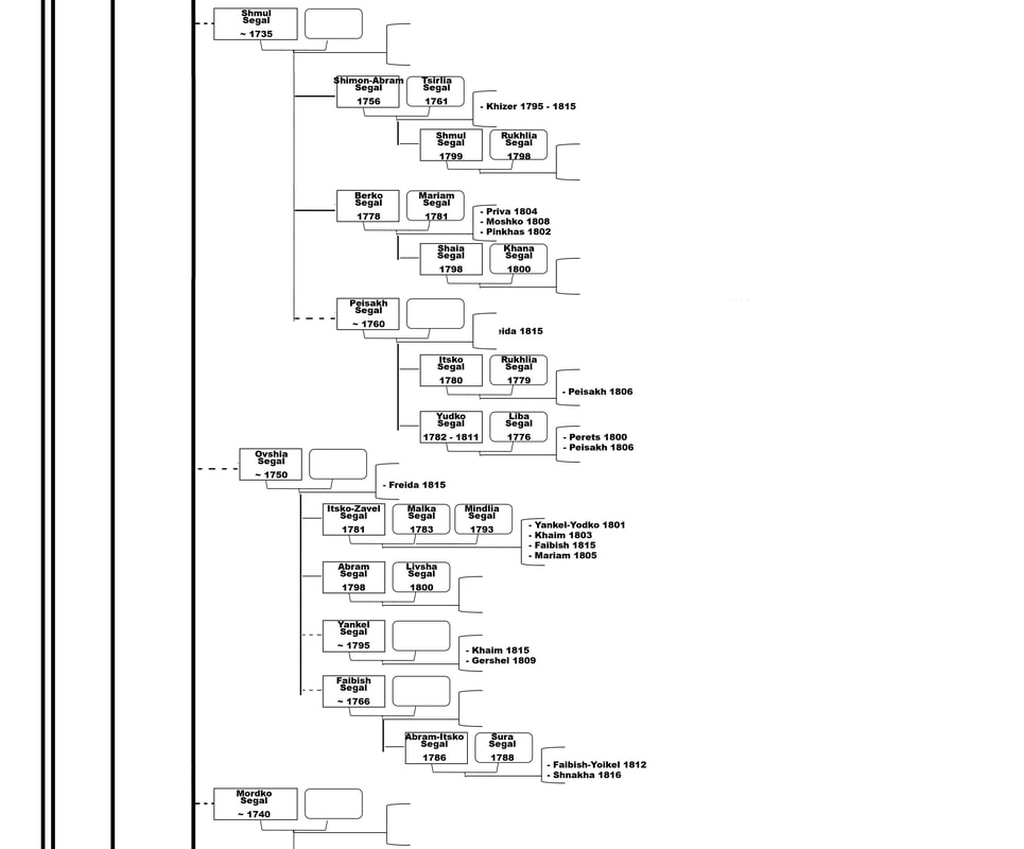

SHMUL SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

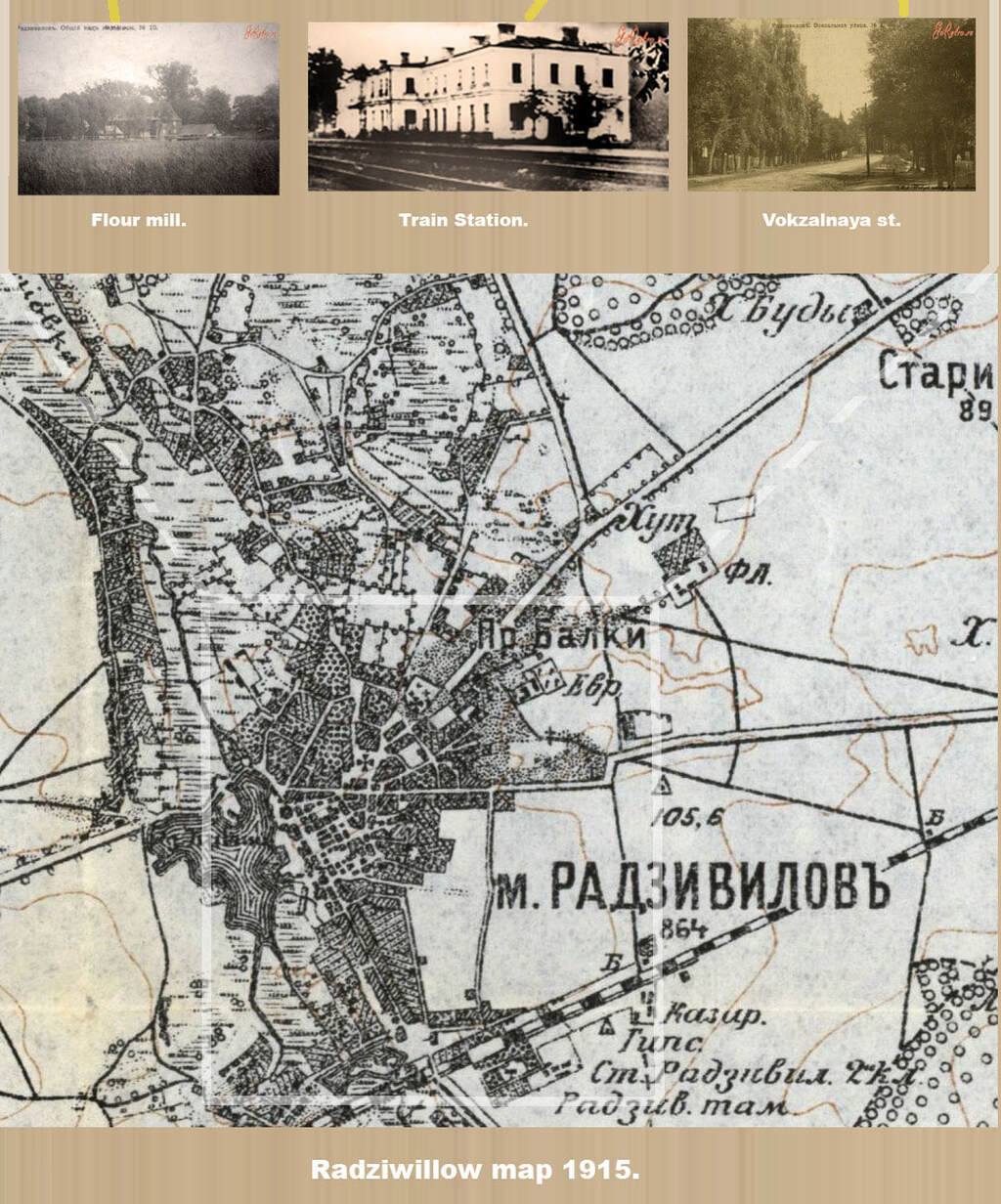

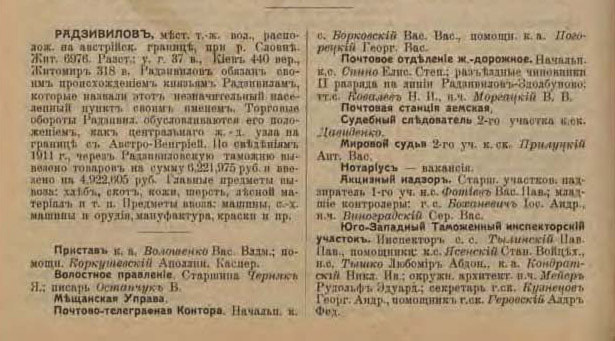

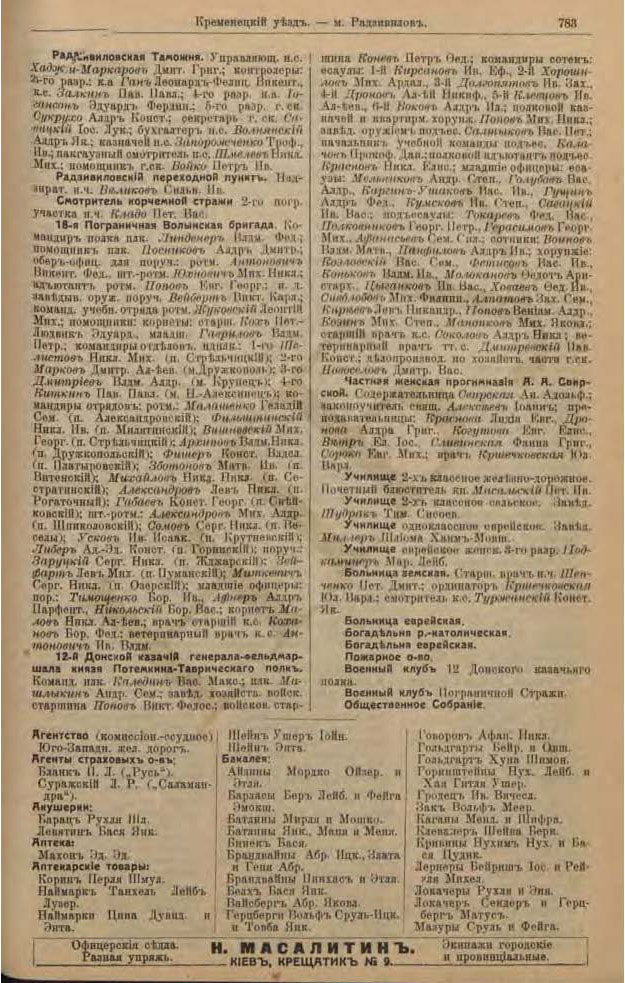

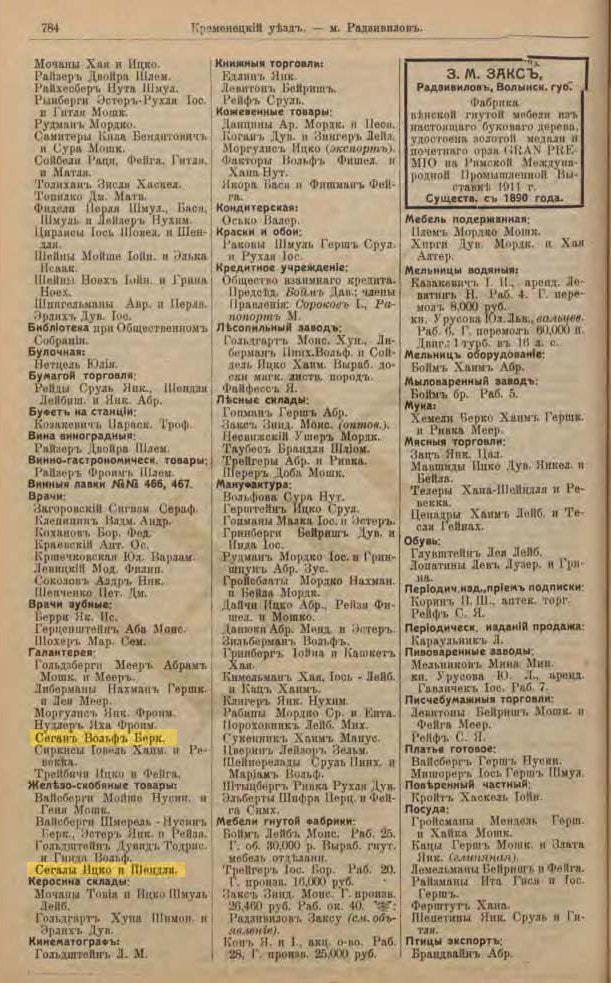

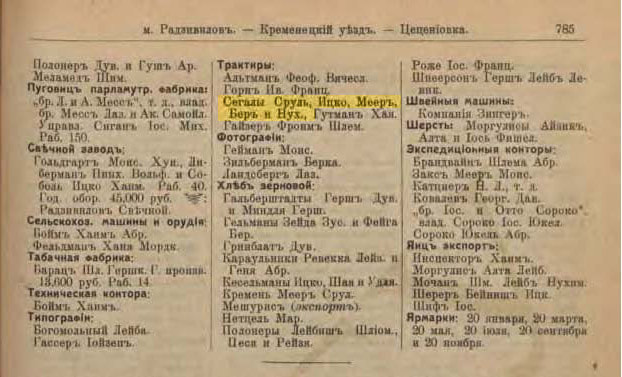

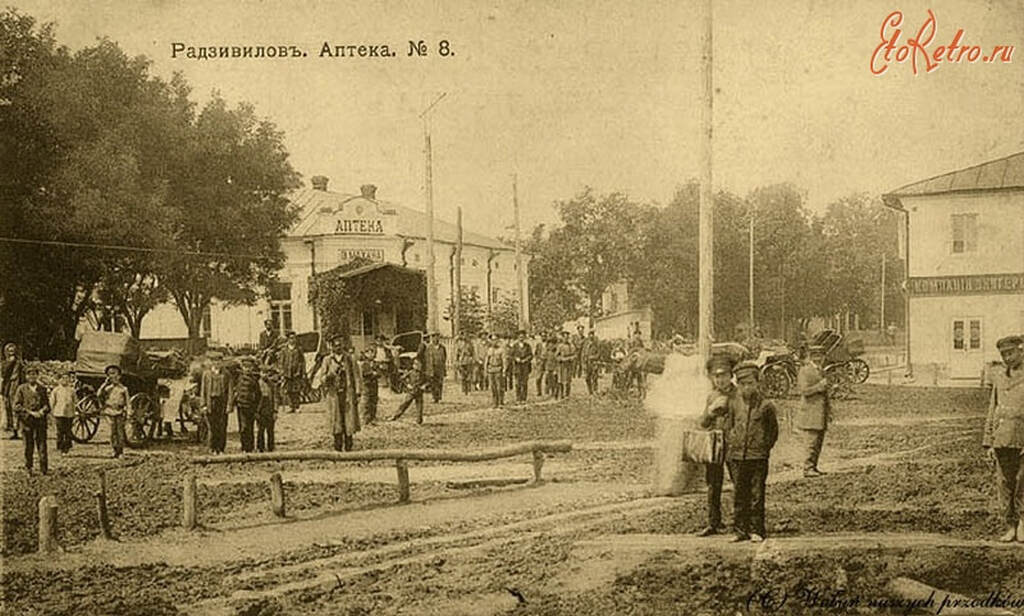

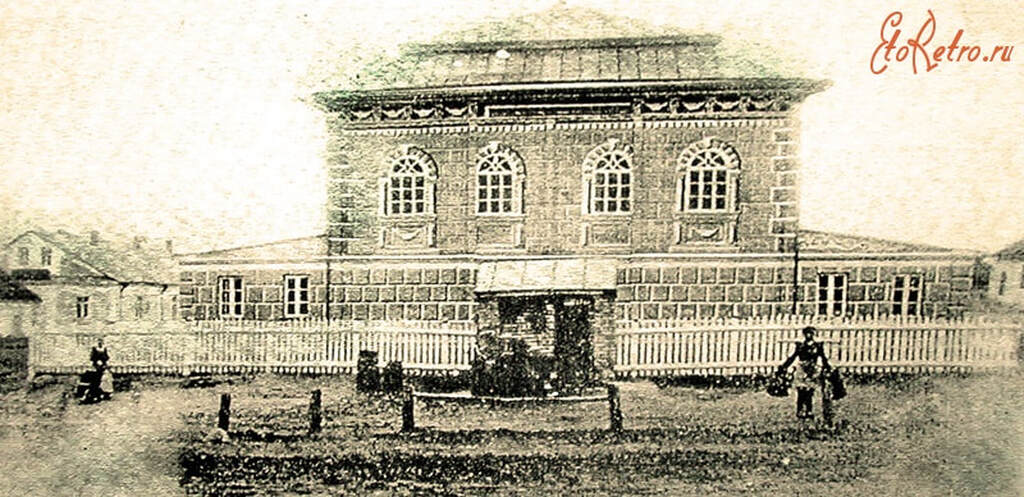

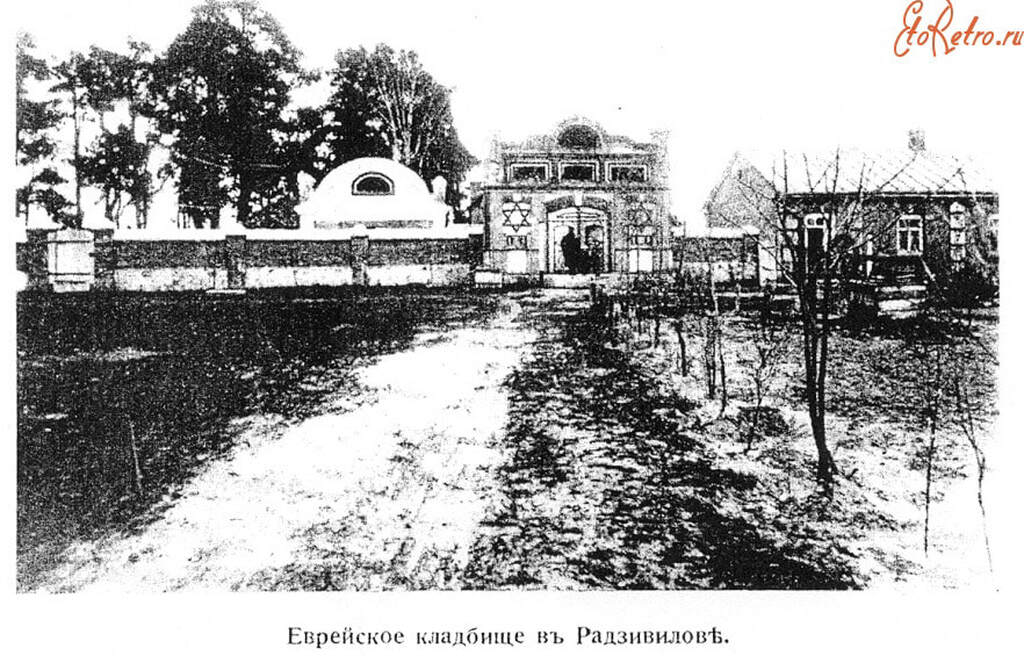

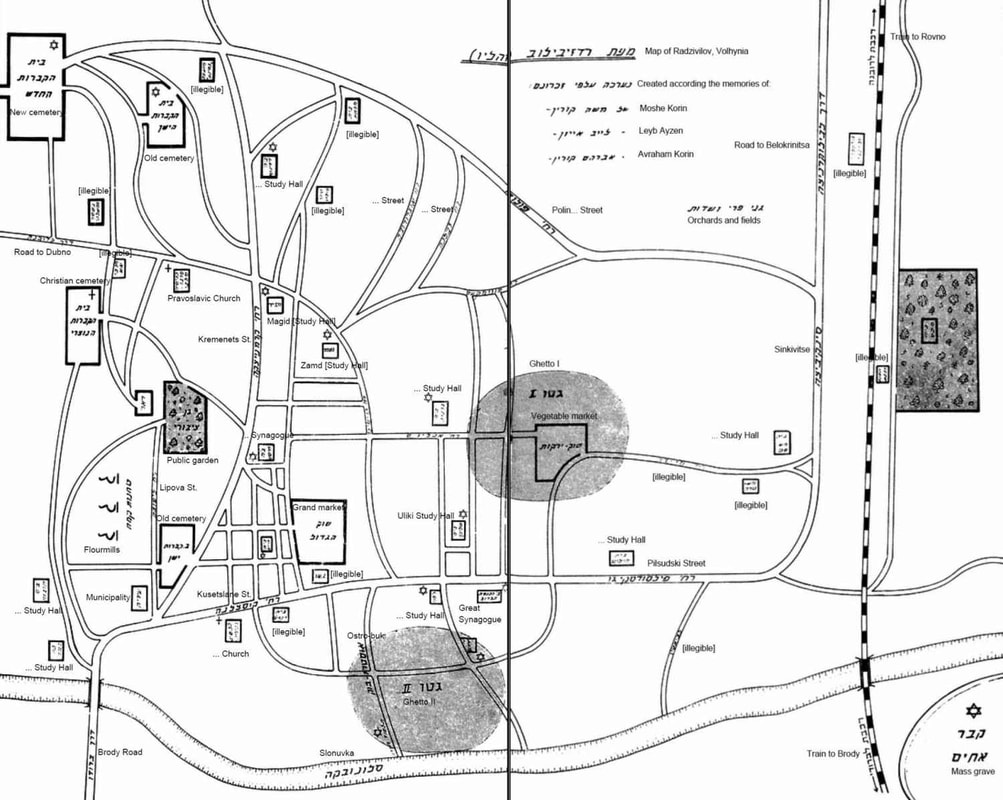

SEGALS FROM RADIVILOV

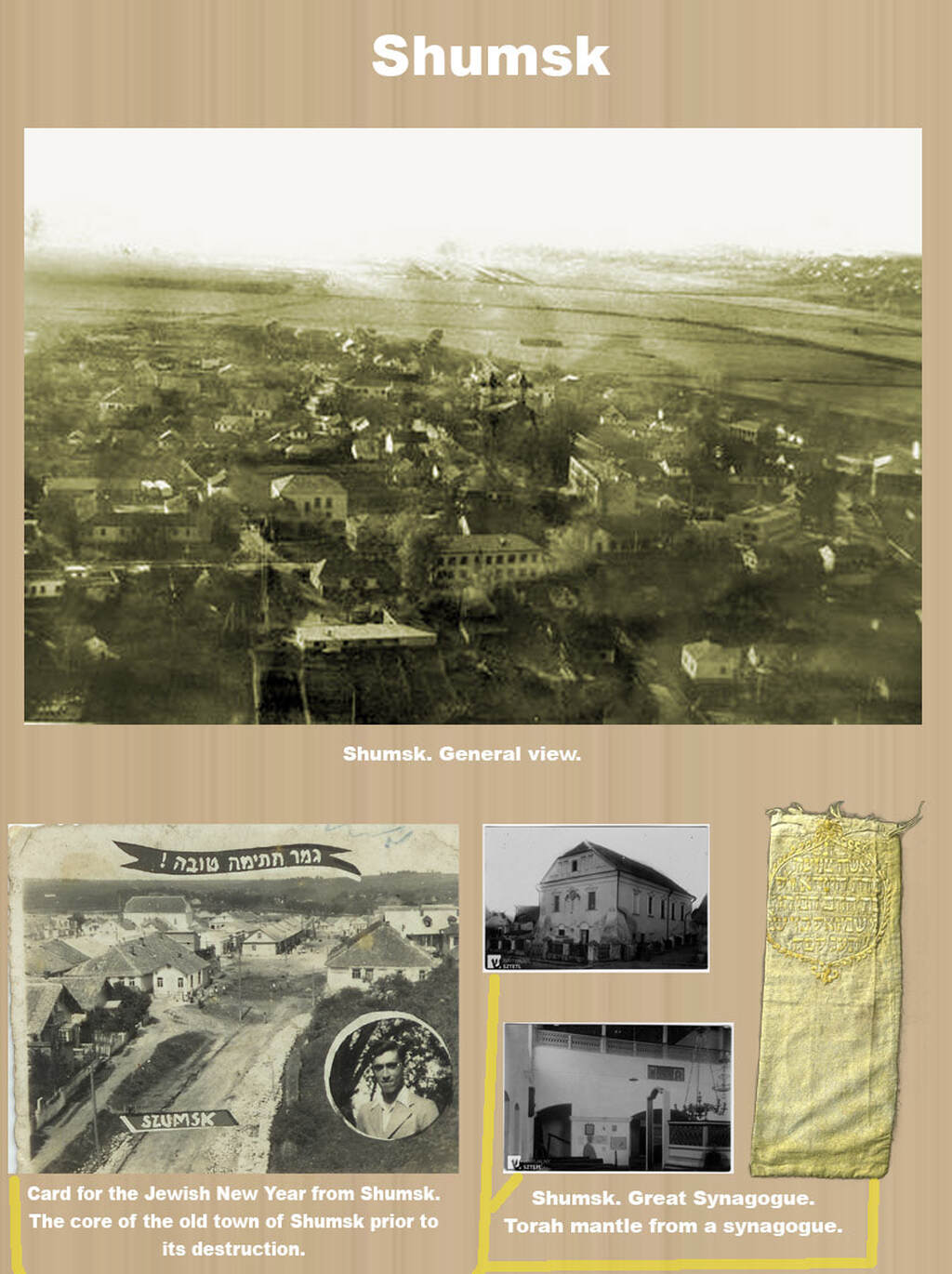

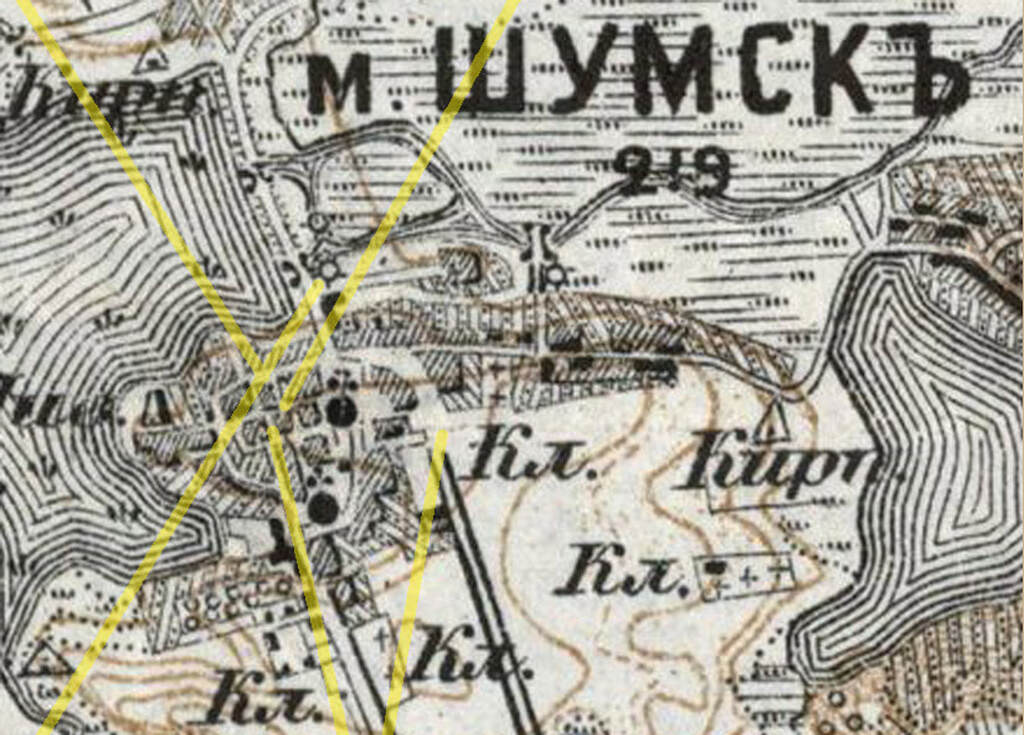

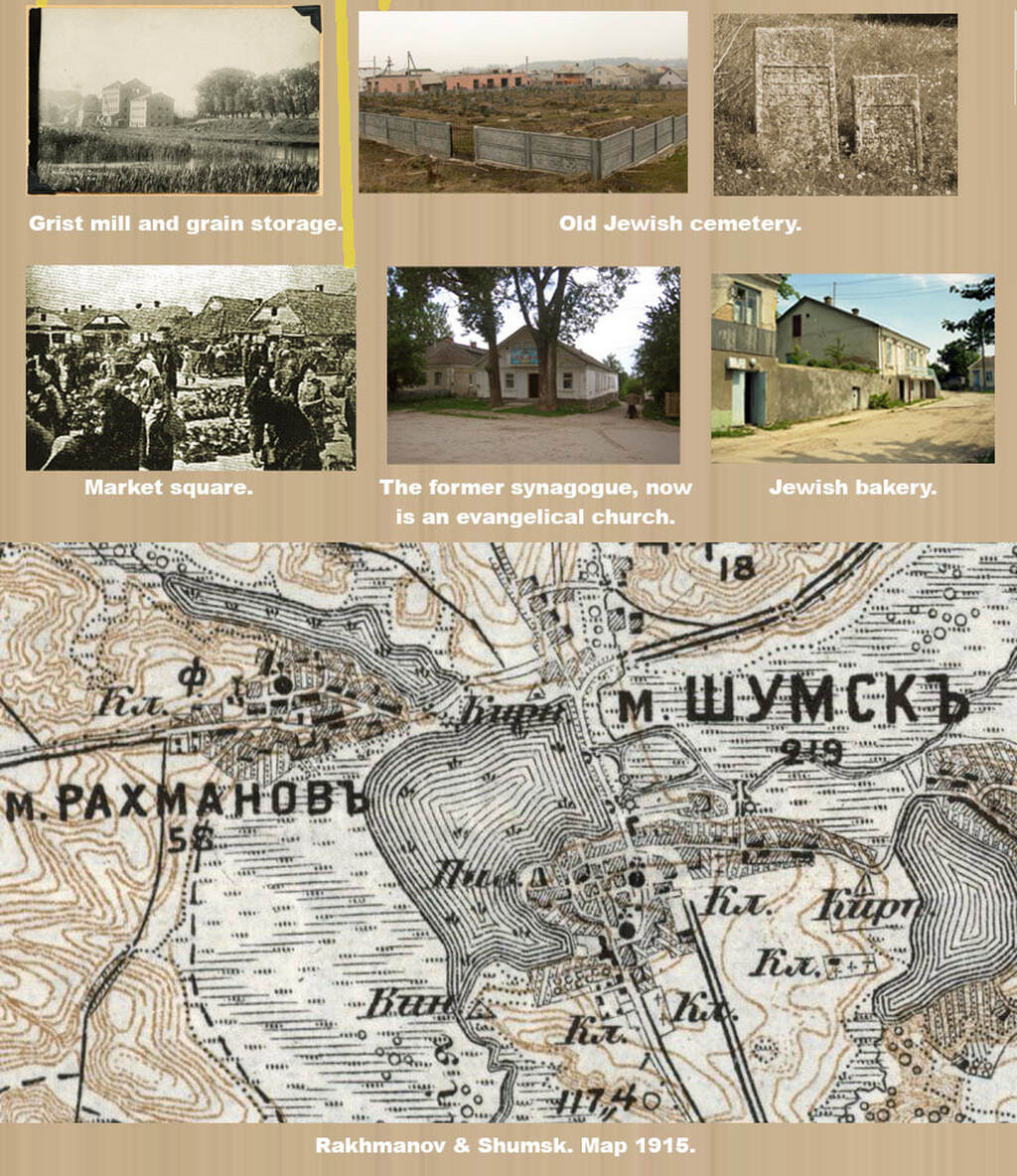

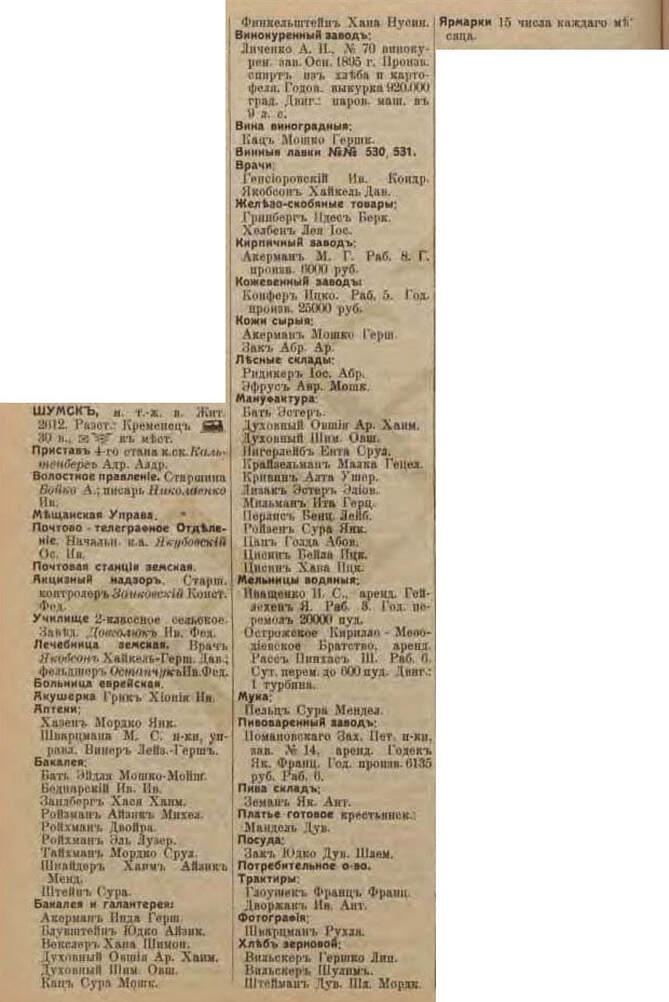

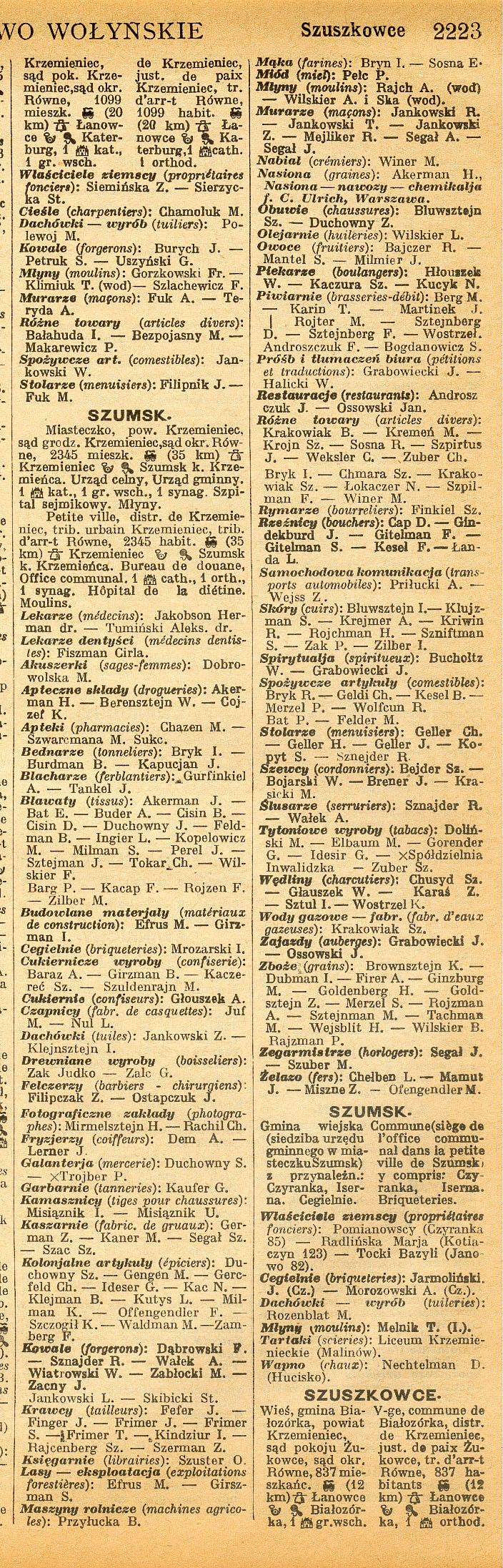

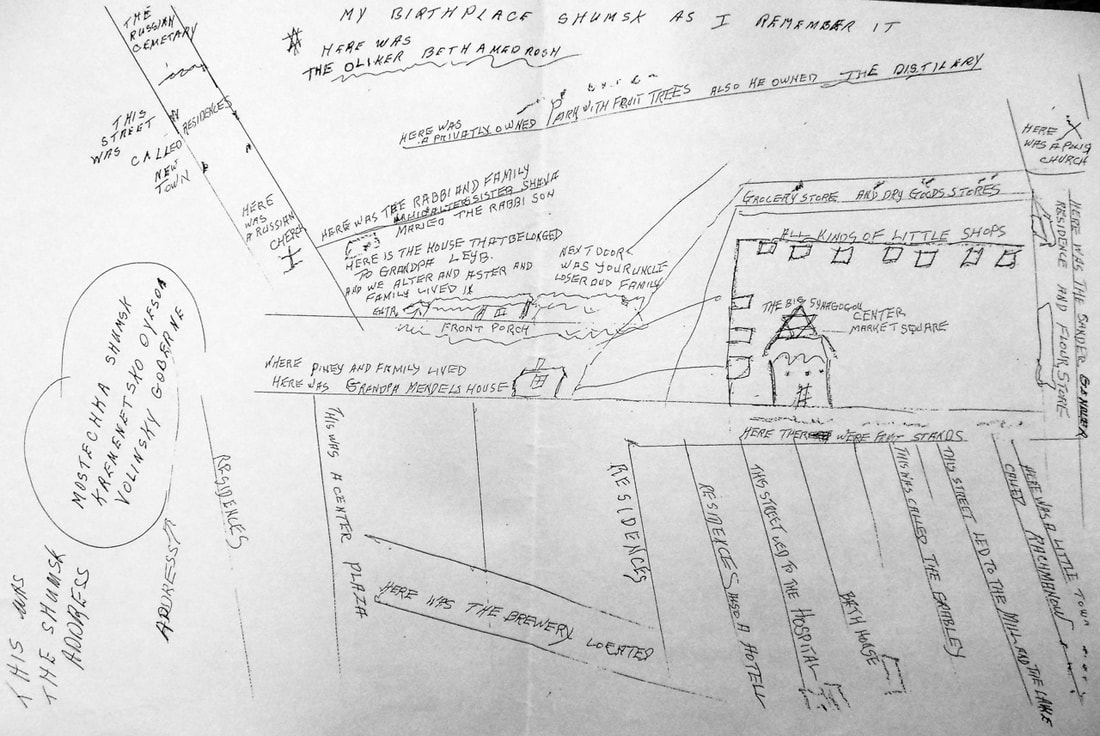

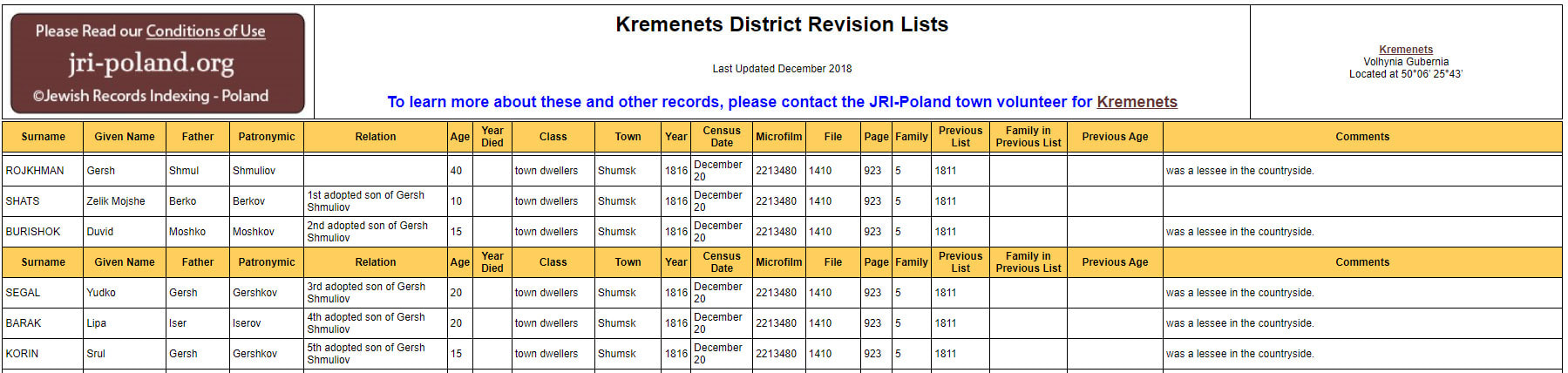

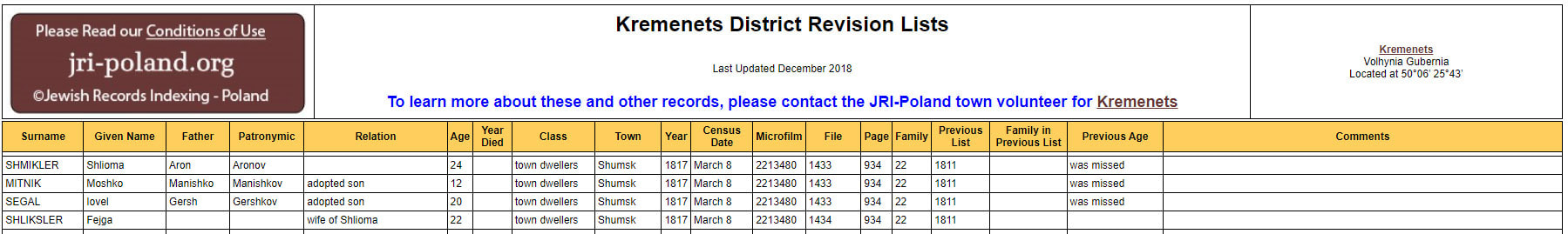

SEGALS FROM SHUMSK

MORDKO SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

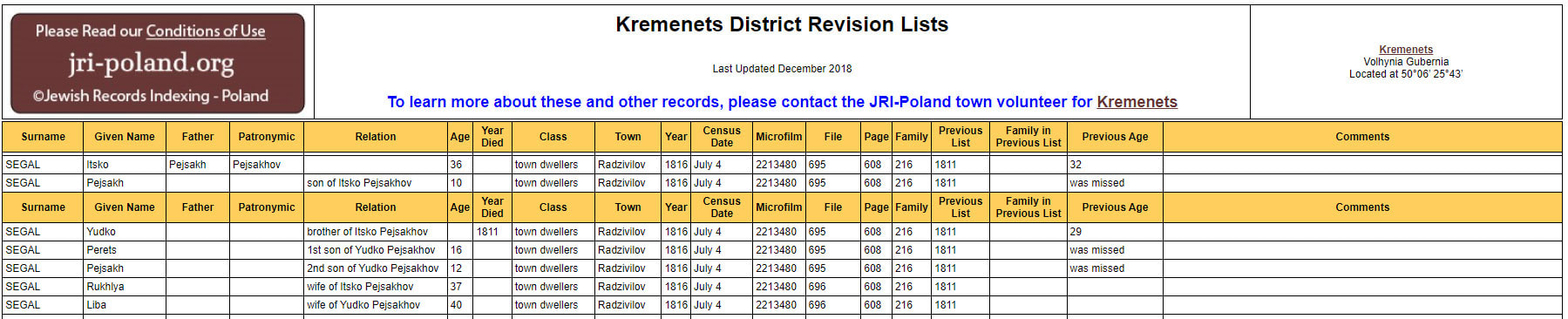

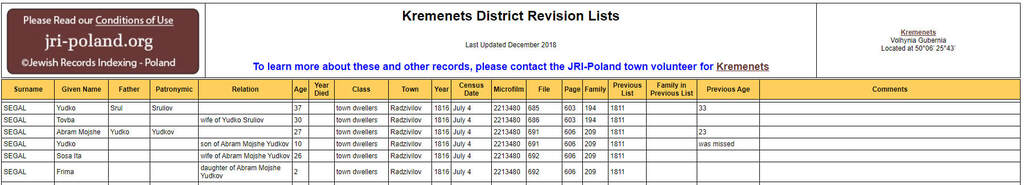

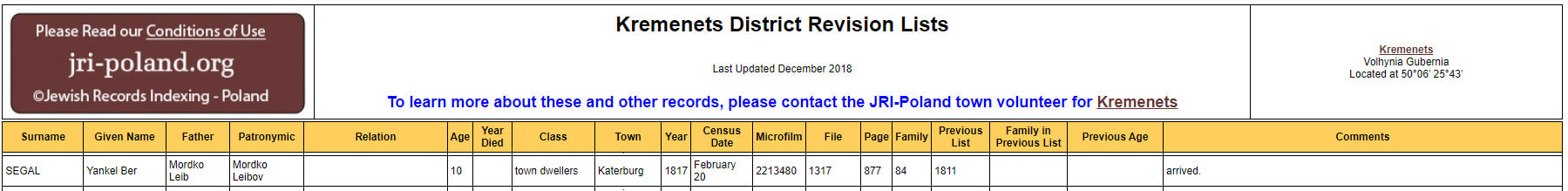

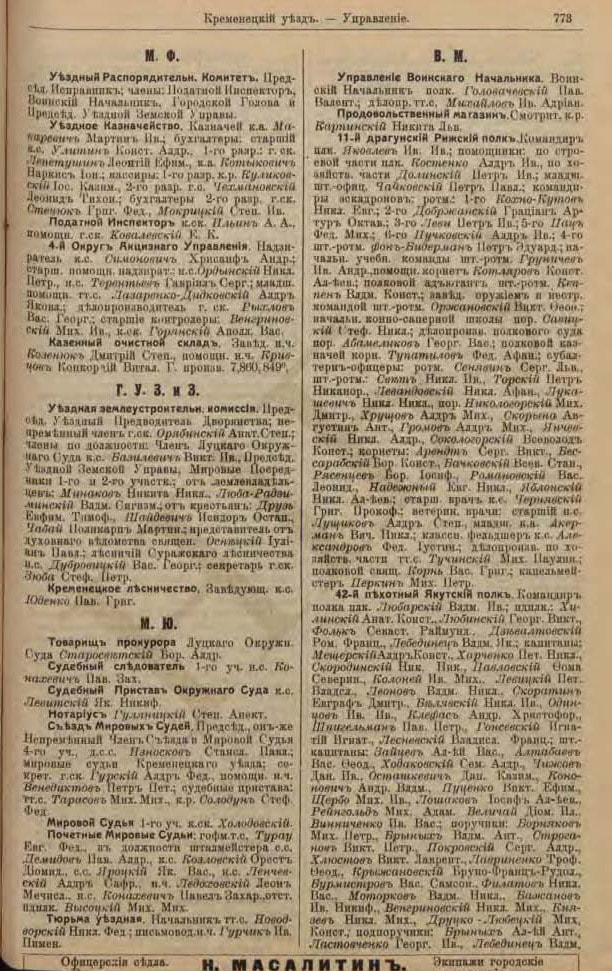

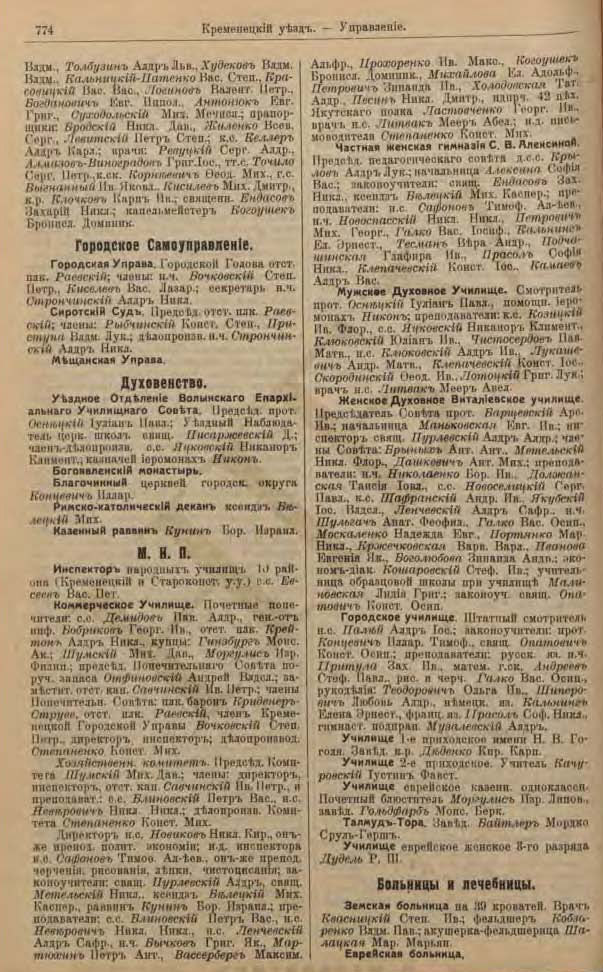

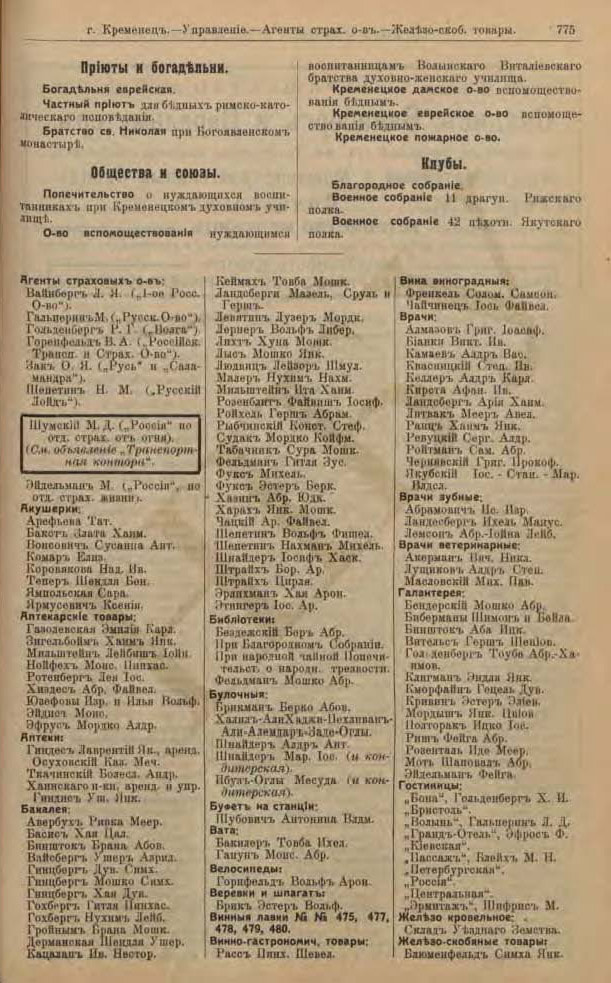

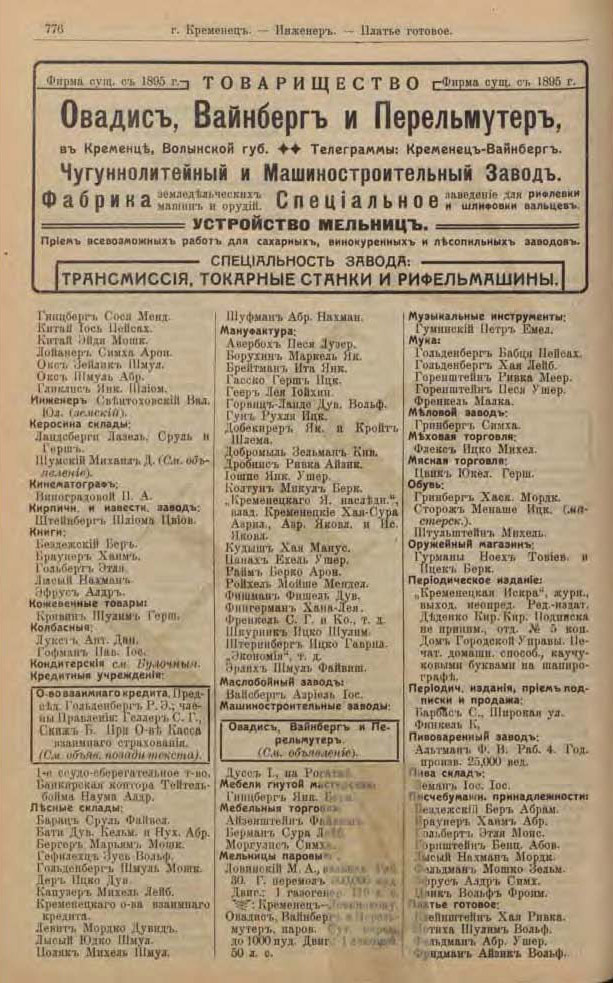

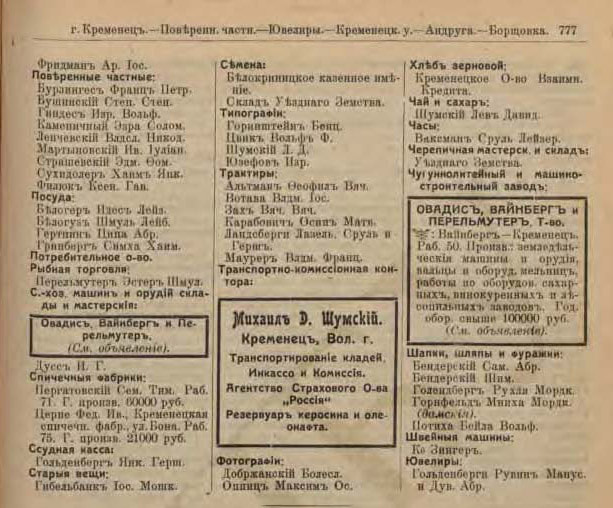

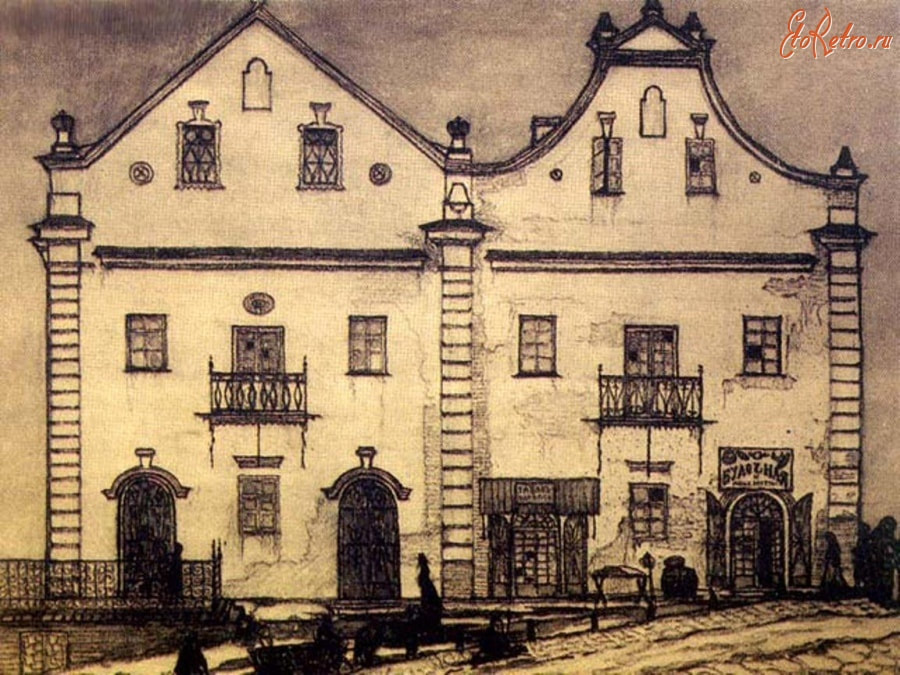

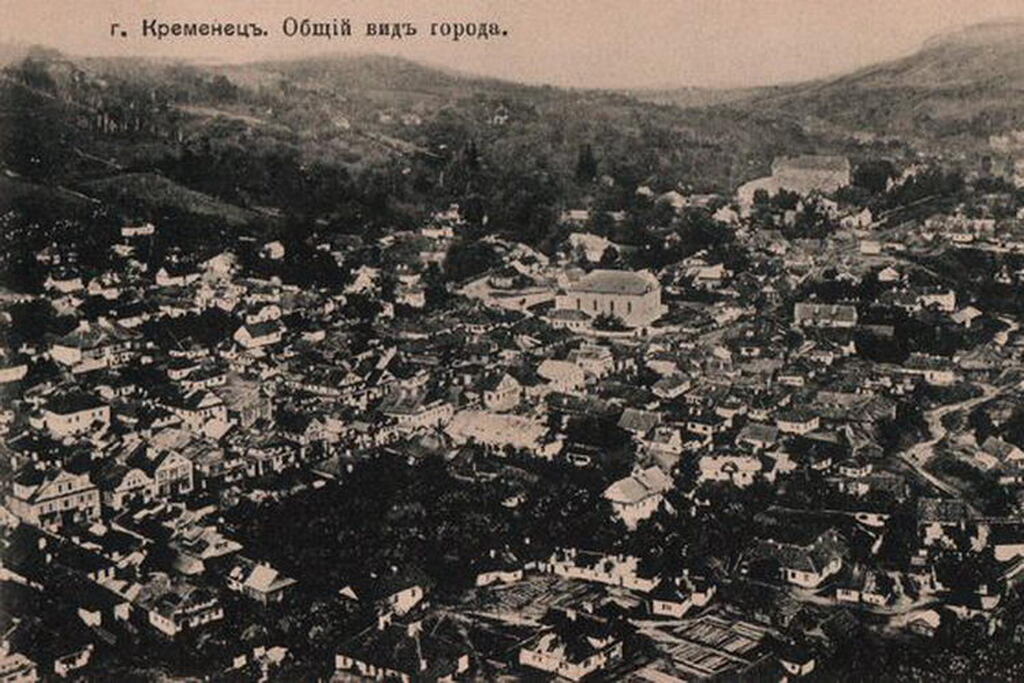

SEGALS FROM KREMENETS

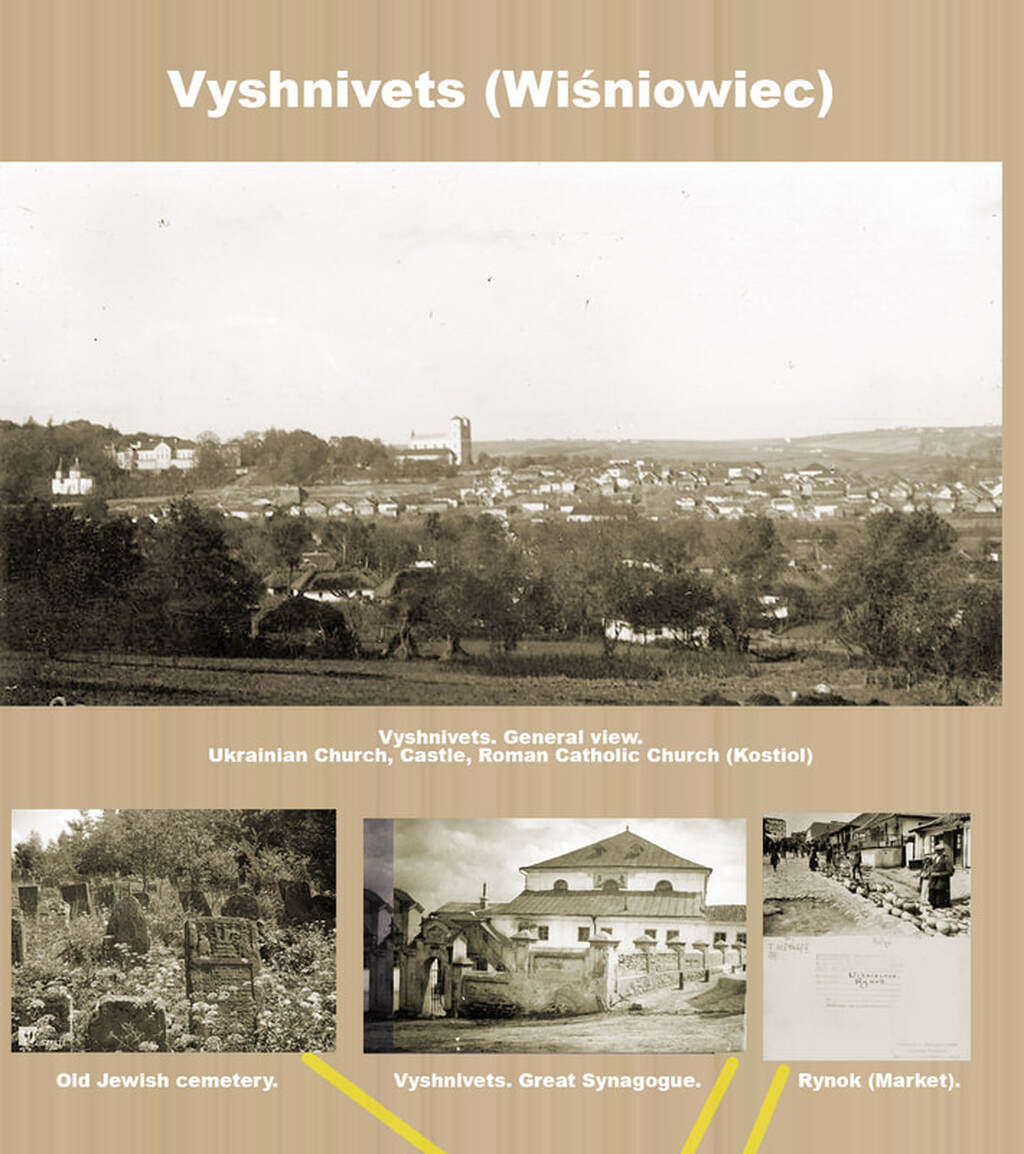

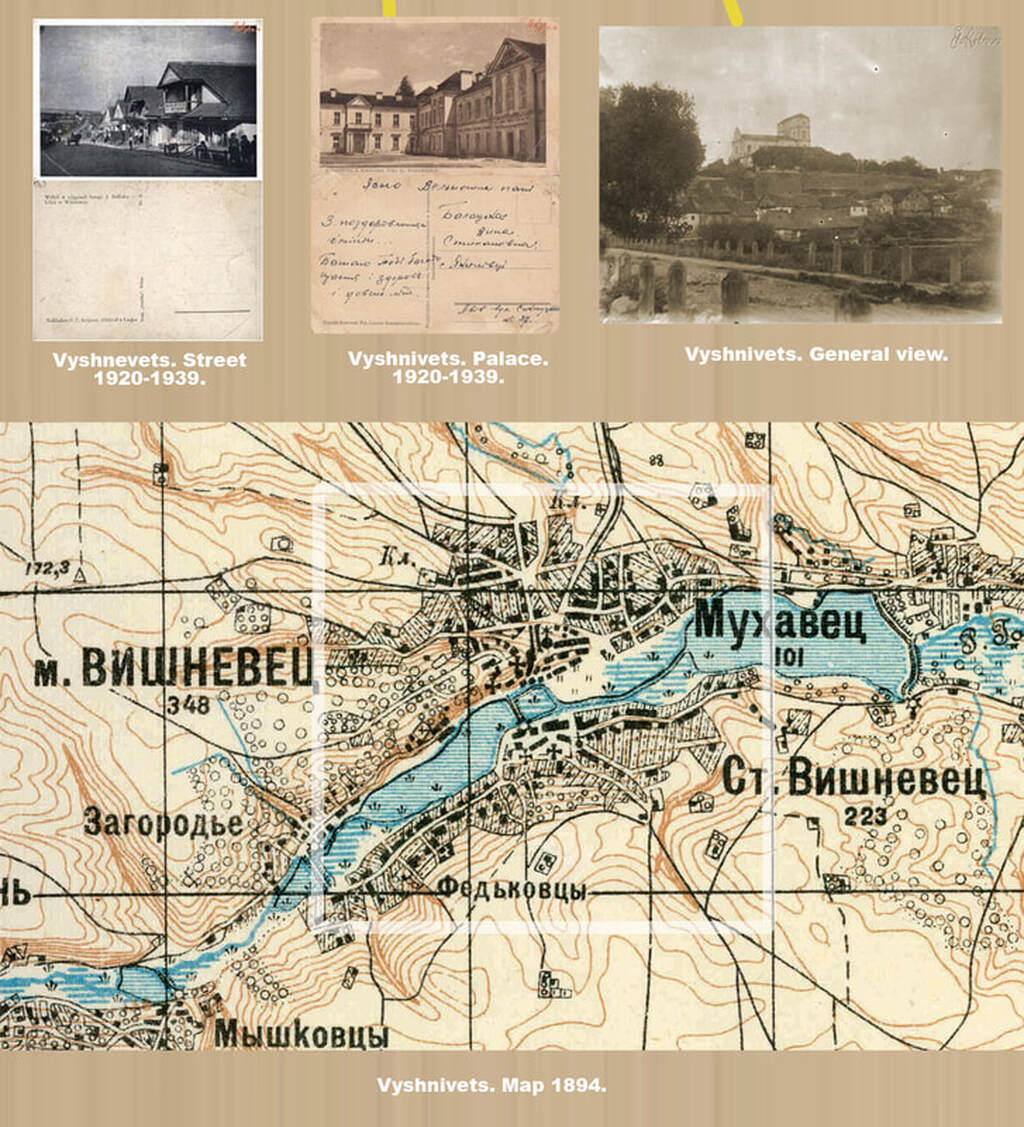

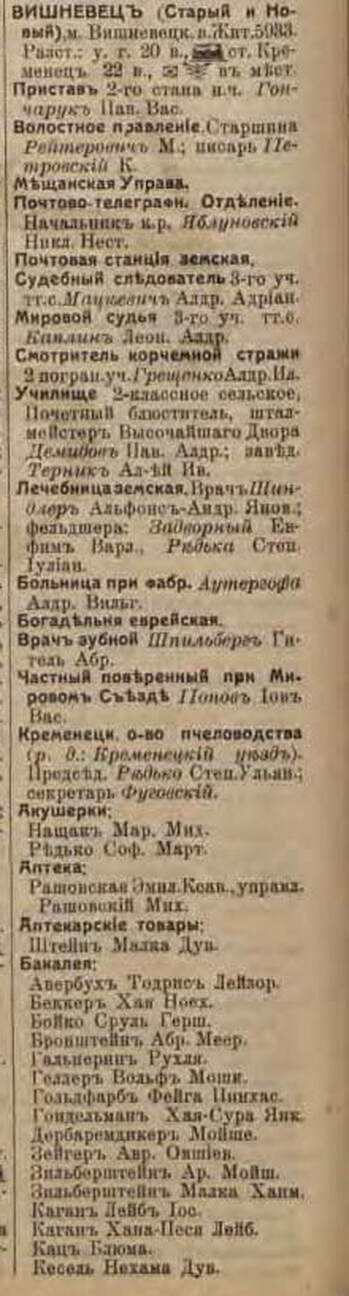

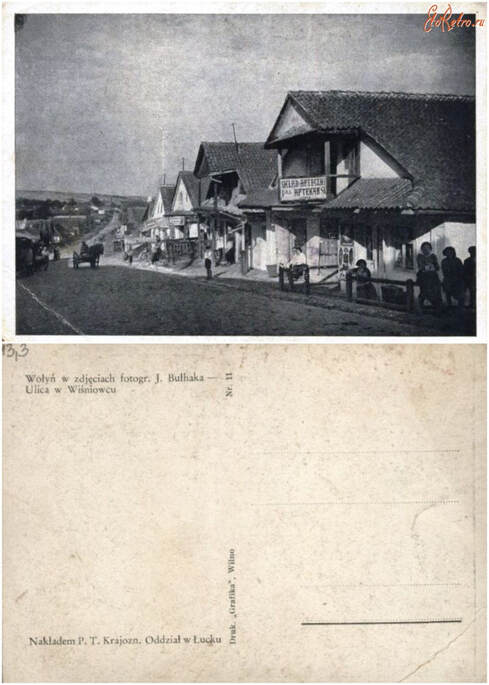

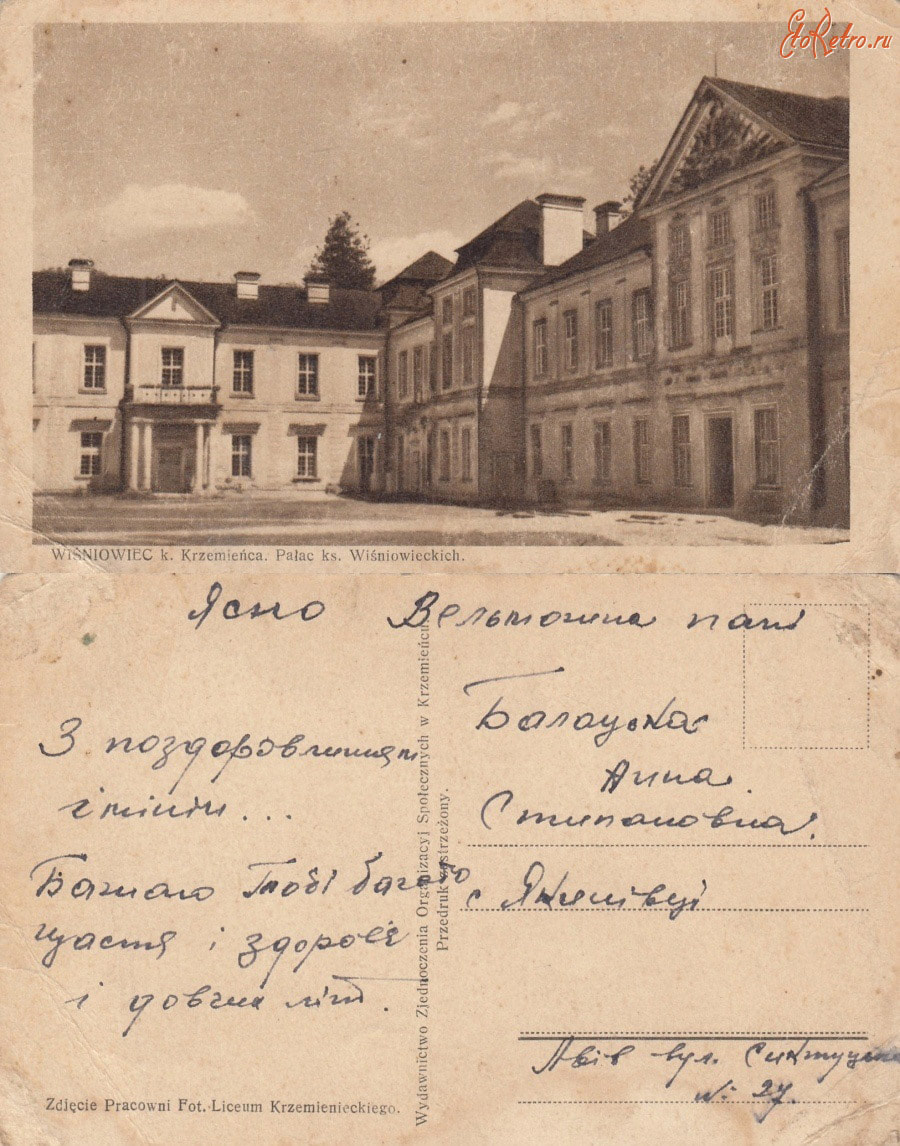

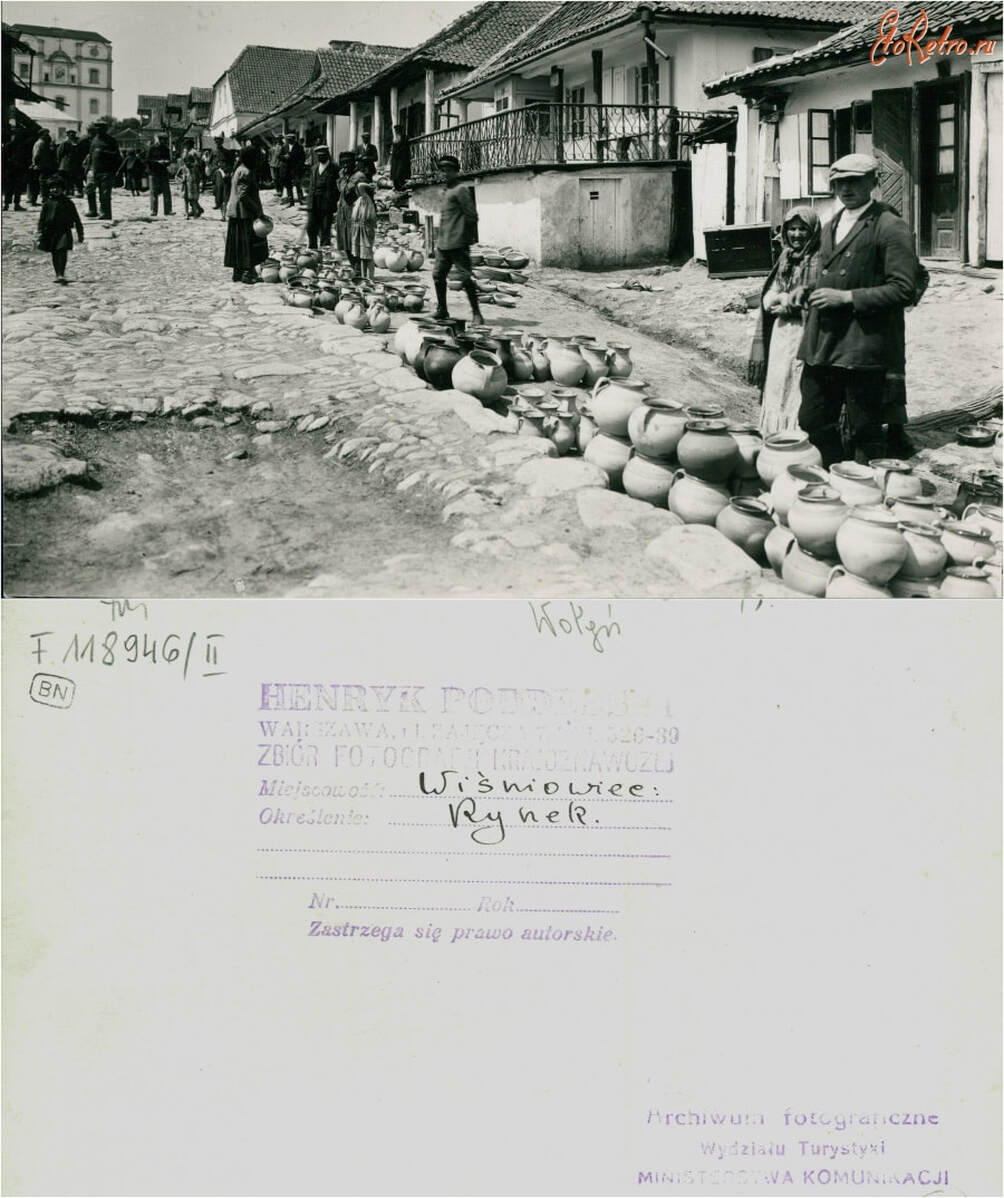

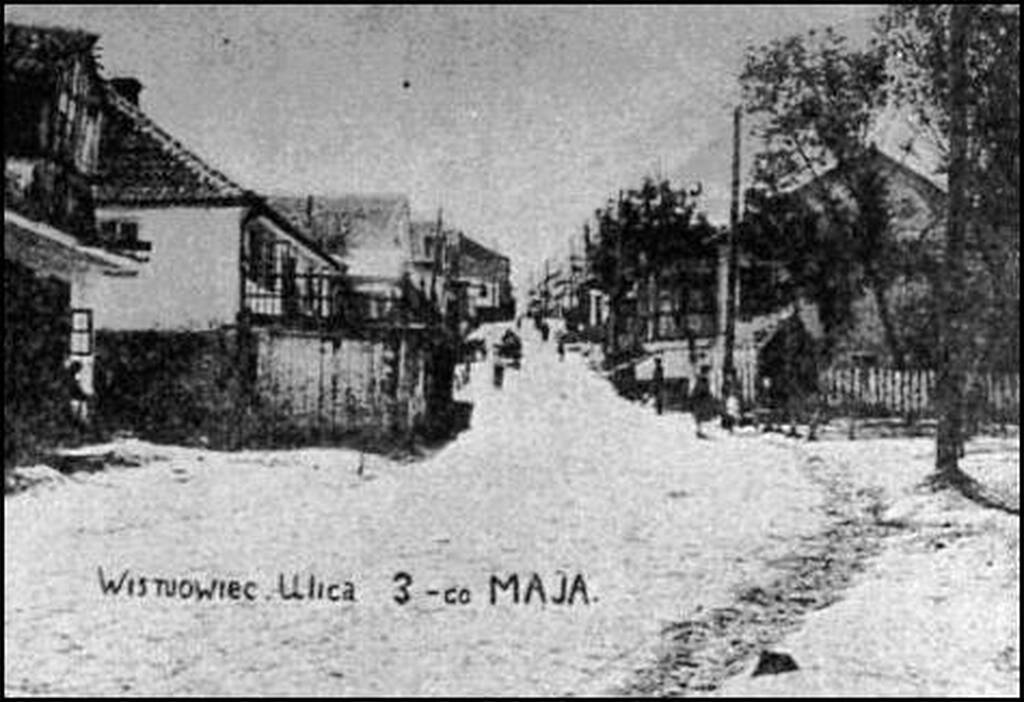

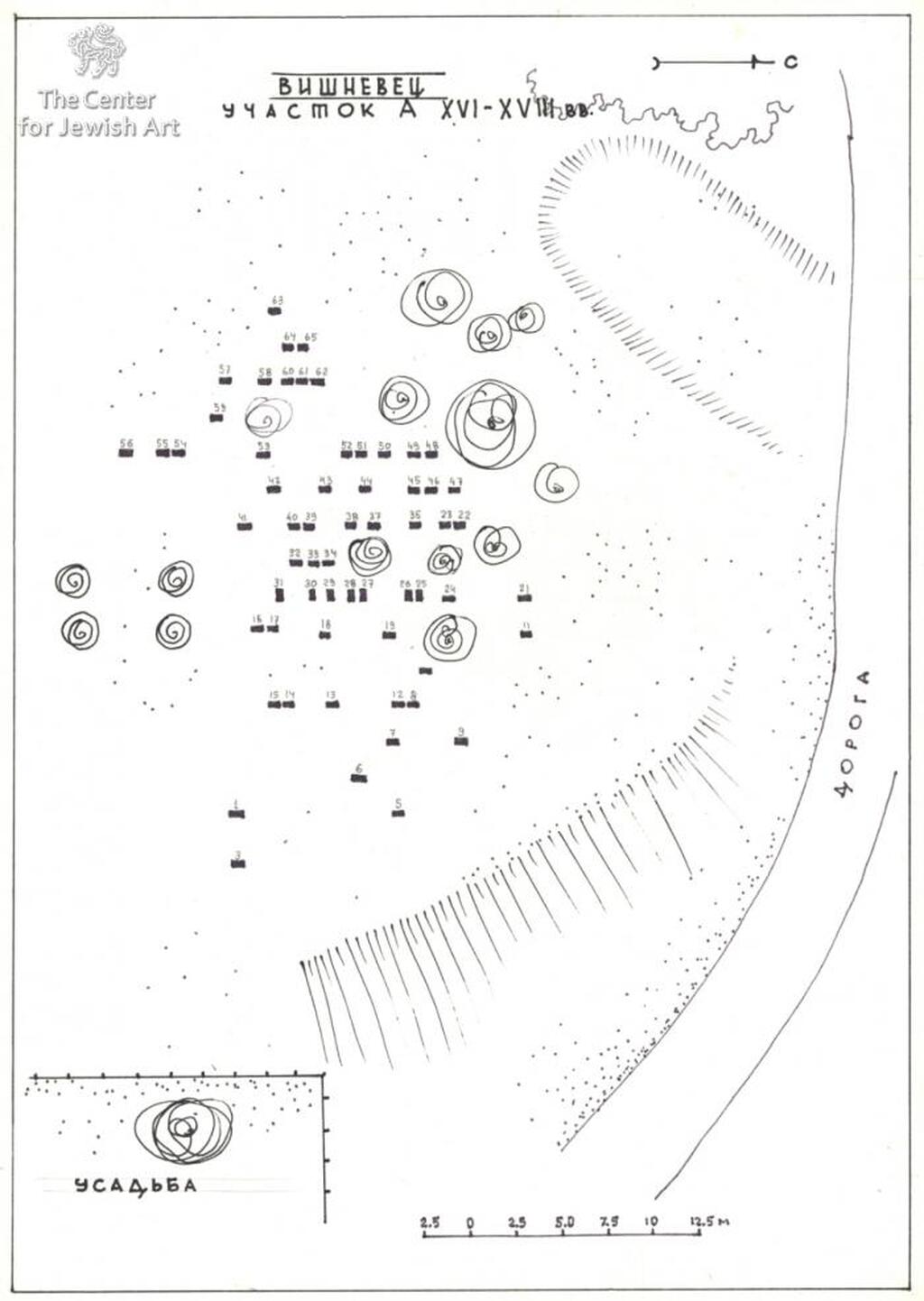

SEGALS FROM VYSHNIVETS

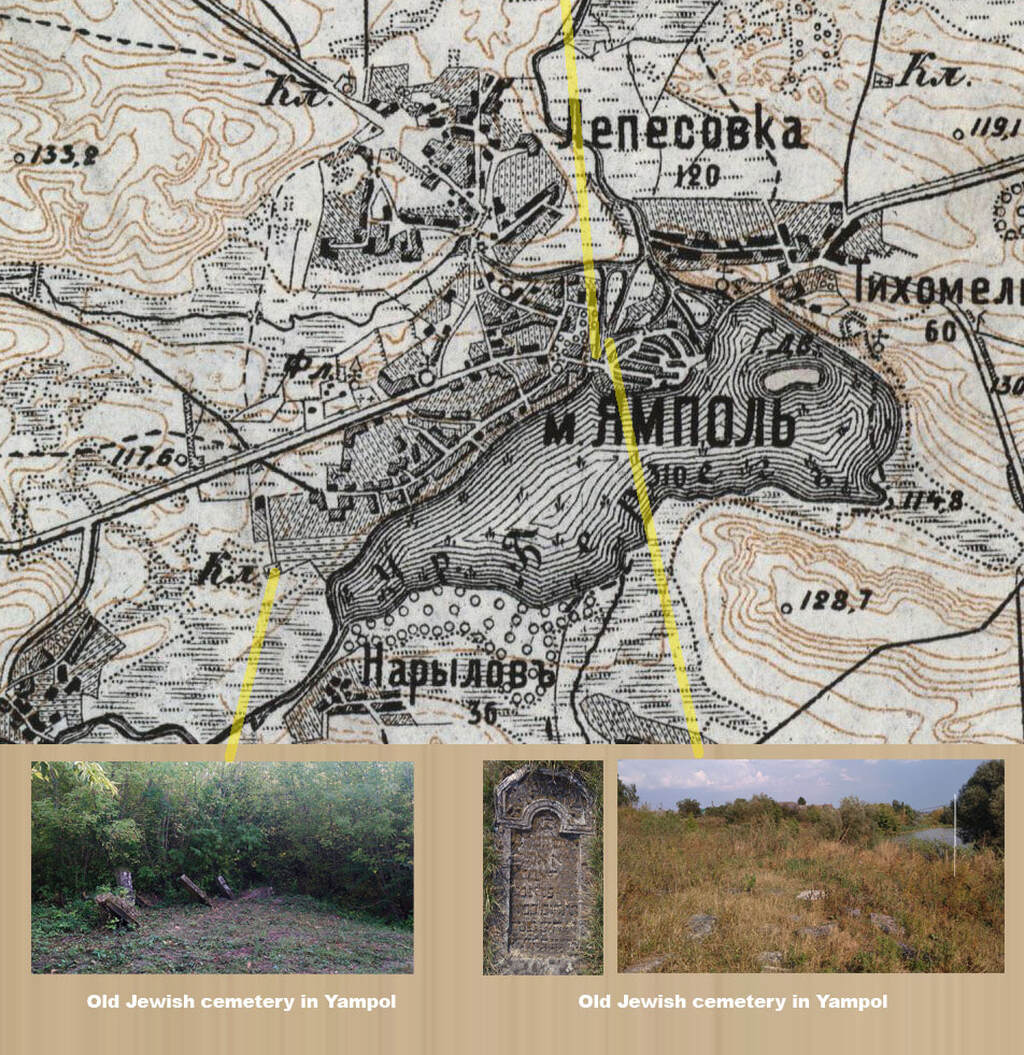

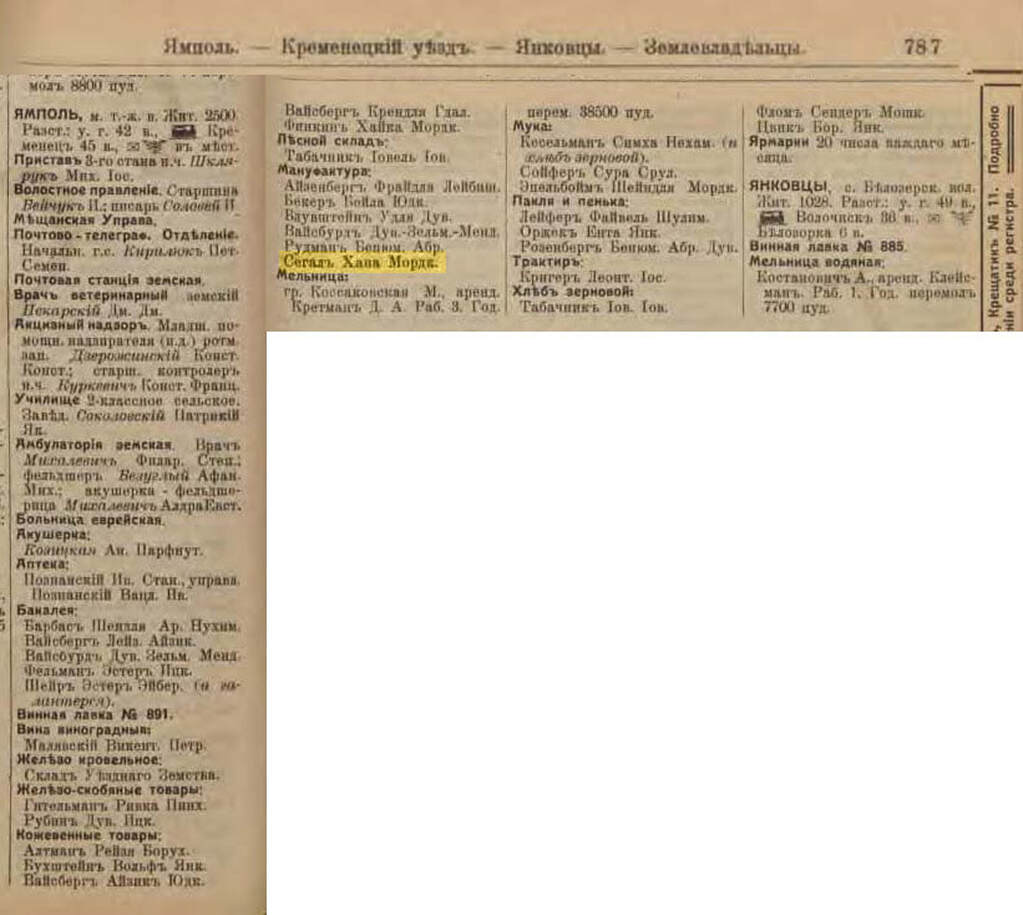

SEGALS FROM YAMPOL

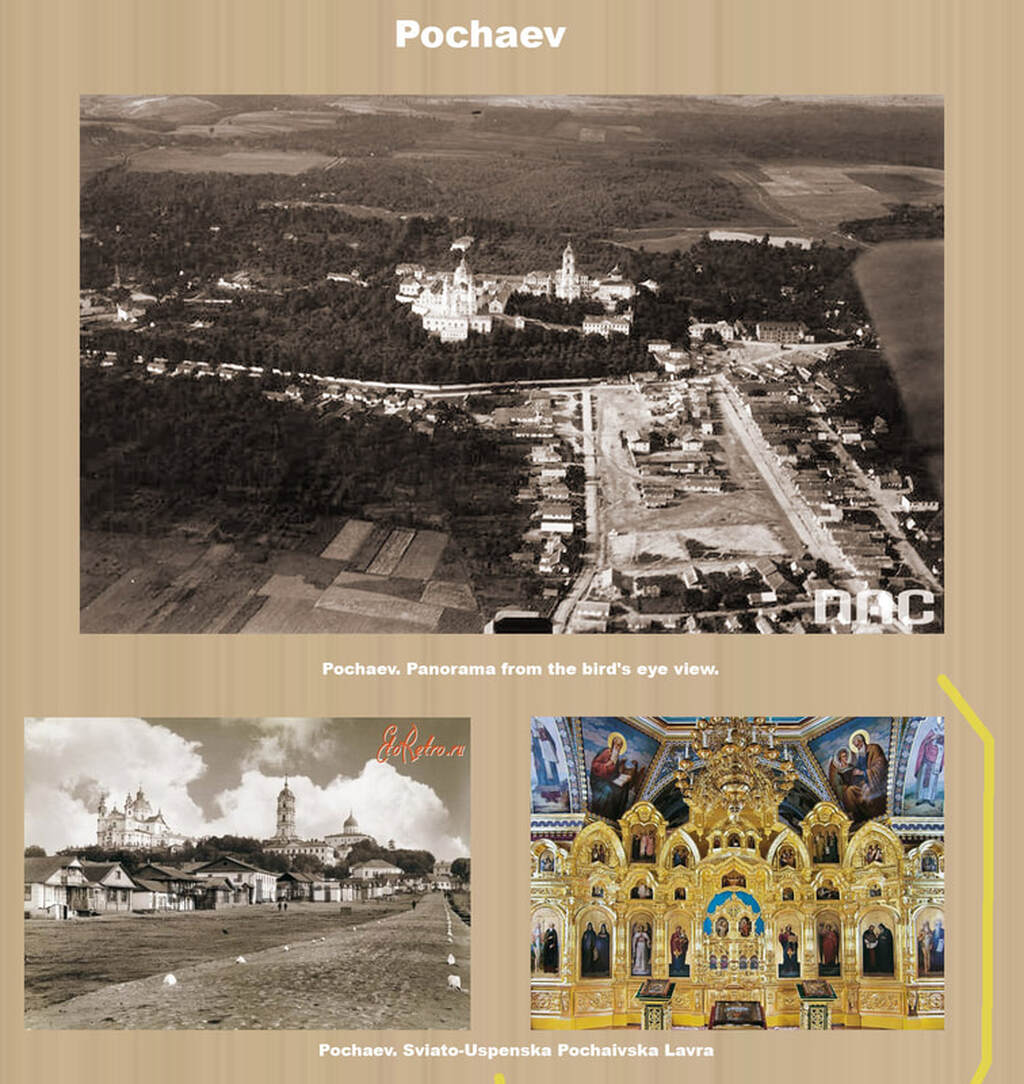

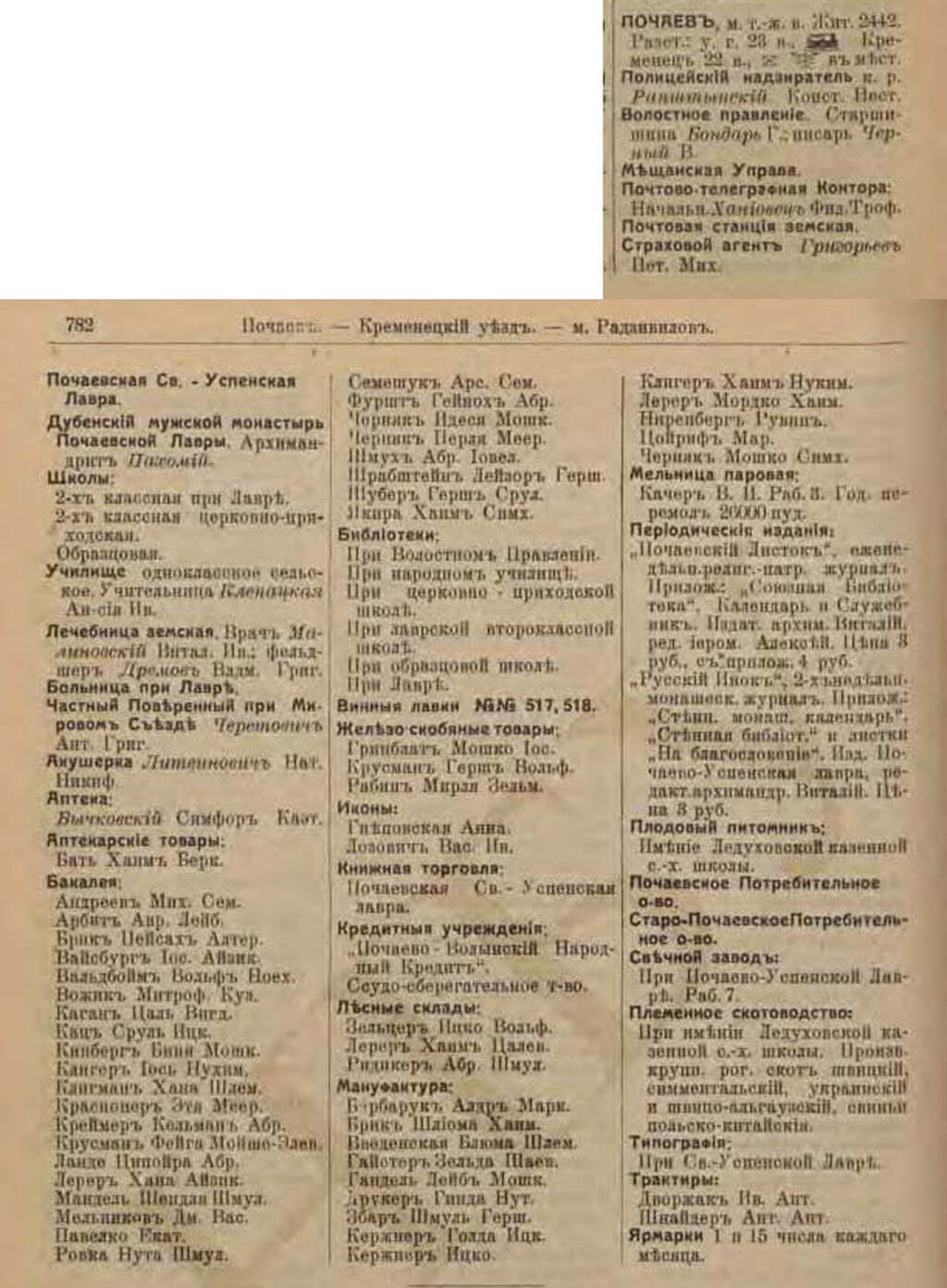

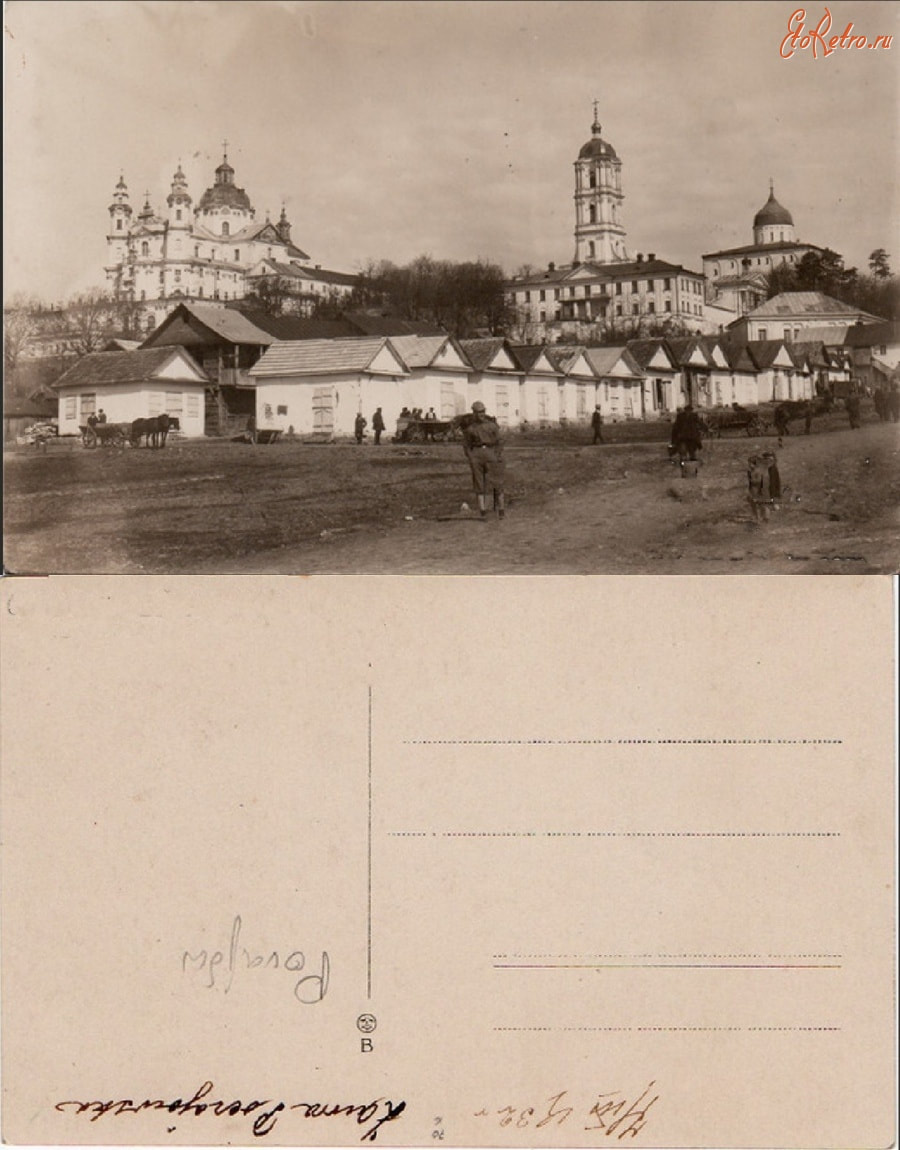

SEGALS FROM POCHAEV

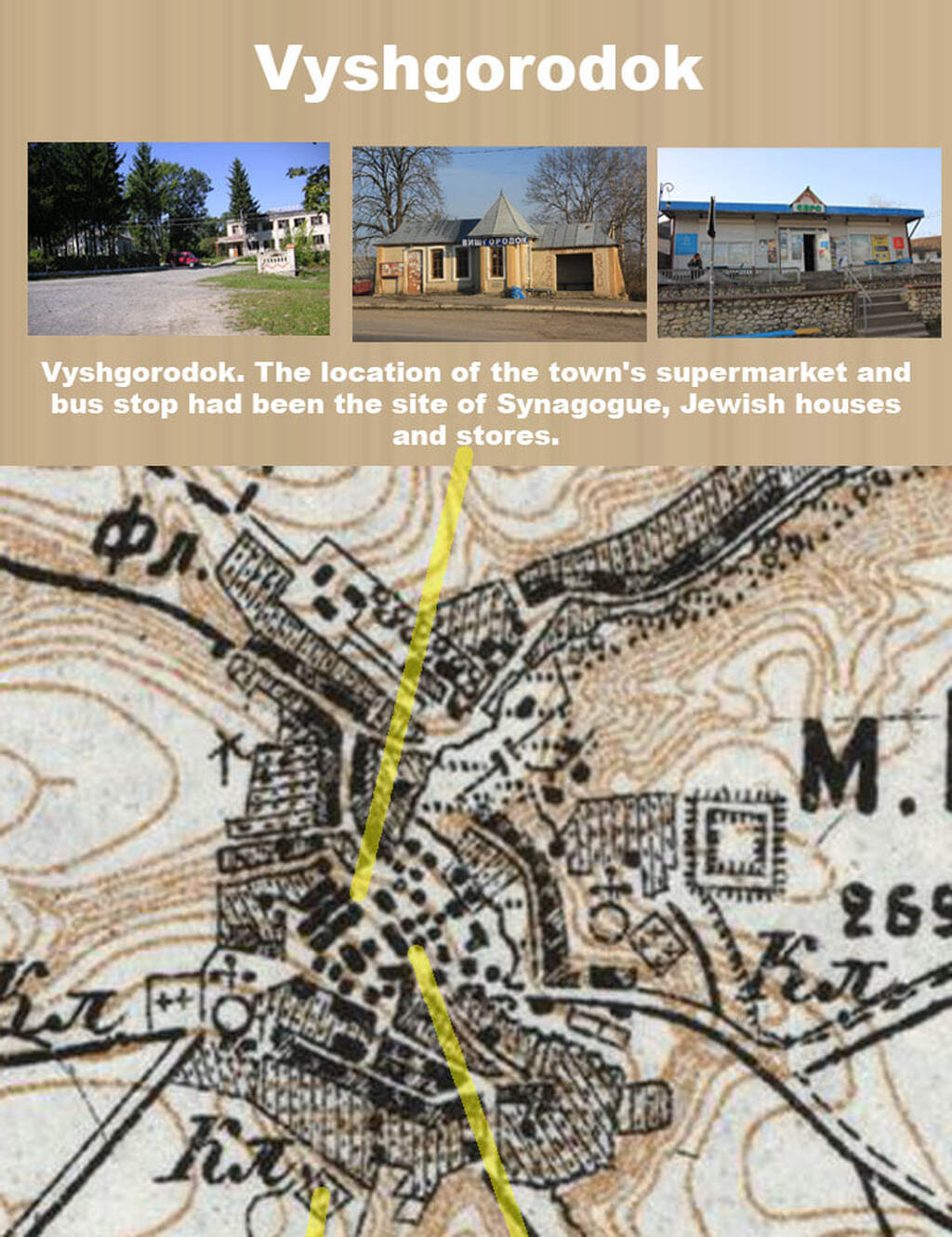

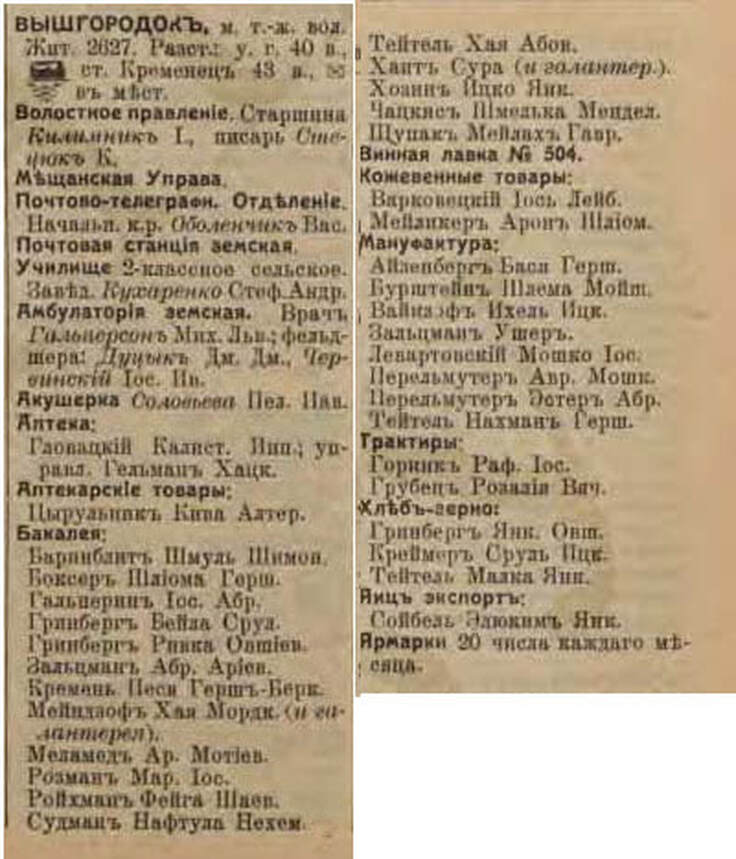

SEGALS FROM VISHGORODOK

MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SHLOMA SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

LEIB SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

KOS SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

BERKO SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

YOS SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

SHIMON SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO

OVSEY BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO)

GERSHKO BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO)

SUB-BRANCHES MOSHKO, LEIBA, ITSKO, BASIA, YANKEL, AVRUMA (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO, GERSHKO BRANCH)

SOKHARA SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO, GERSHKO BRANCH)

DUVID SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO, GERSHKO BRANCH)

DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO

USHER BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO)

VOLKO BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO)

GERSHKO SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

SHENDER SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

MIKHAIL SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

SHLOMO SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

OUR ANCESTORS FROM FASTOV

ABRAM BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO)

LEIB SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

CHASKEL LEYBOVICH FAMILY (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAMA BRANCH, SUB-BRANCH LEIB)

DAVID-MORDUKH YOSELEVICH FAMILY (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH, SUB-BRANCH LEIB)

YOS SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

MOSHKO SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV FAMILY TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

MEER SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

DUVID SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

YANKEL SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

RADOMYSL

RADOMYSL - BUSINESS PEOPLE IN 1895, 1899, 1913.

OTHER SAGALOV NEAR RADOMYSL

OUR ANCESTORS FROM THE CITY OF RADOMYSL

OUR ANCESTORS FROM THE CITY OF MALIN

THE ORIGIN OF JEWISH NAMES IN OUR FAMILY

SCARY TIMES FOR OUR RADOMYSL ANCESTORS

INTRODUCTION

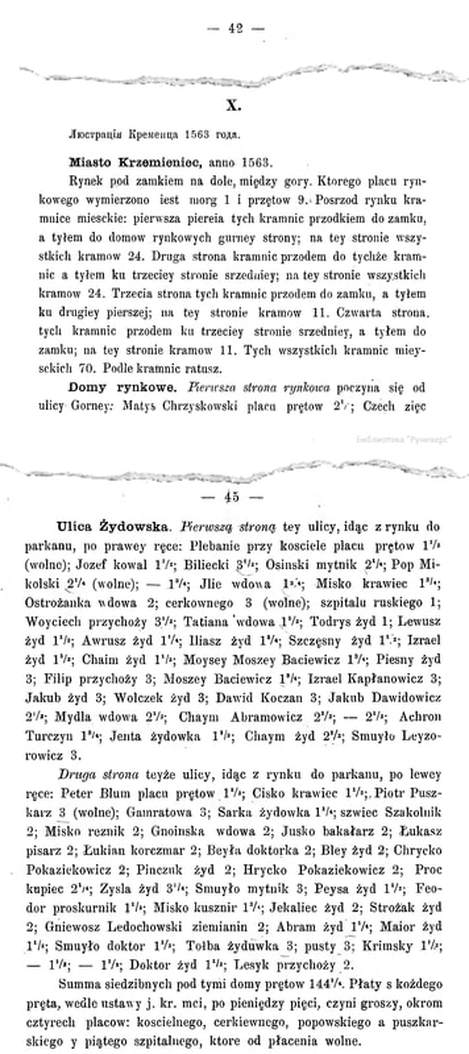

OUR ANCESTORS UP TO THE 18TH CENTURY

SAGALOV FAMILY IN UKRAINE

DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK SEGAL

KHAIM BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK)

AYZIK SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

ABRAM SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

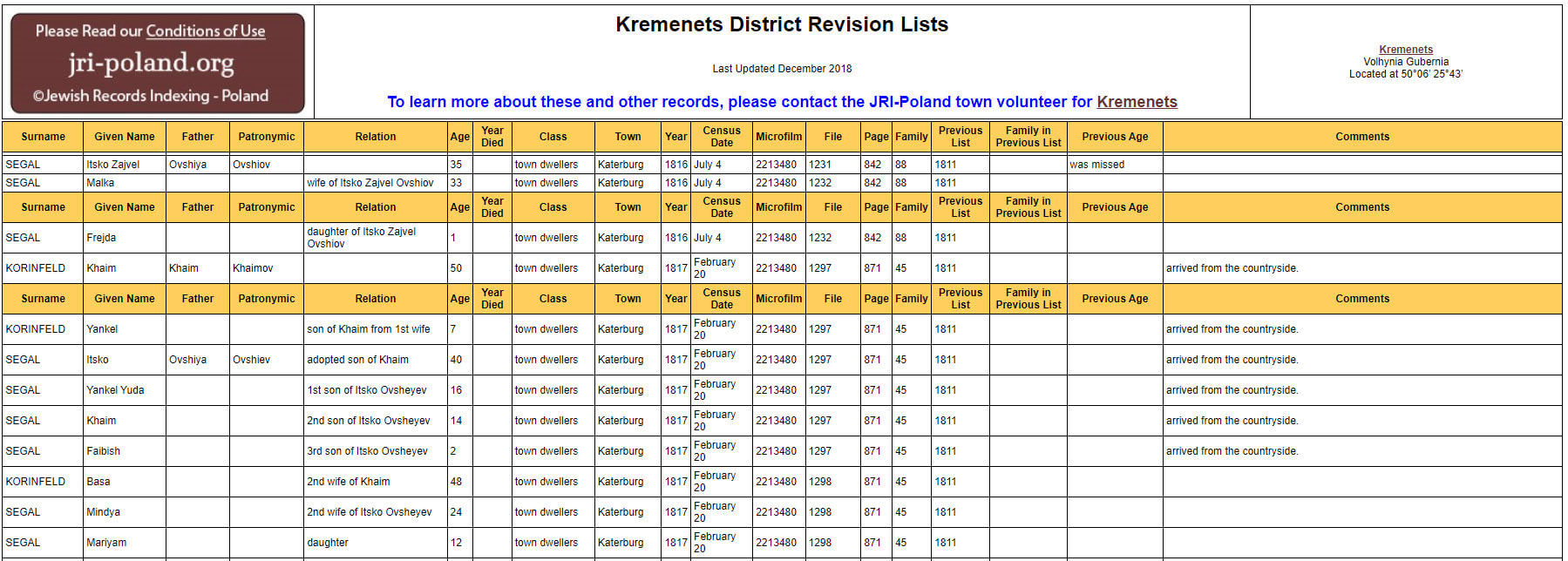

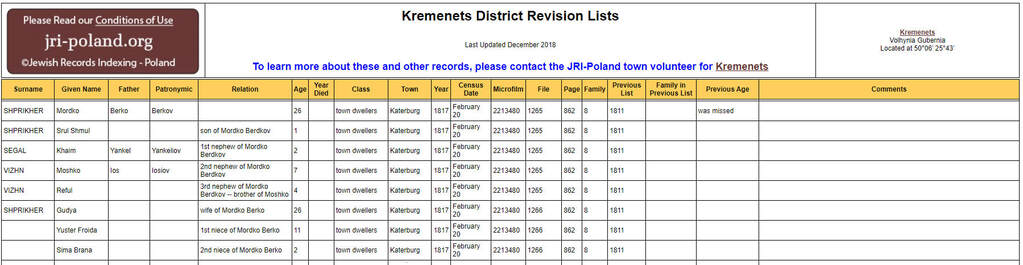

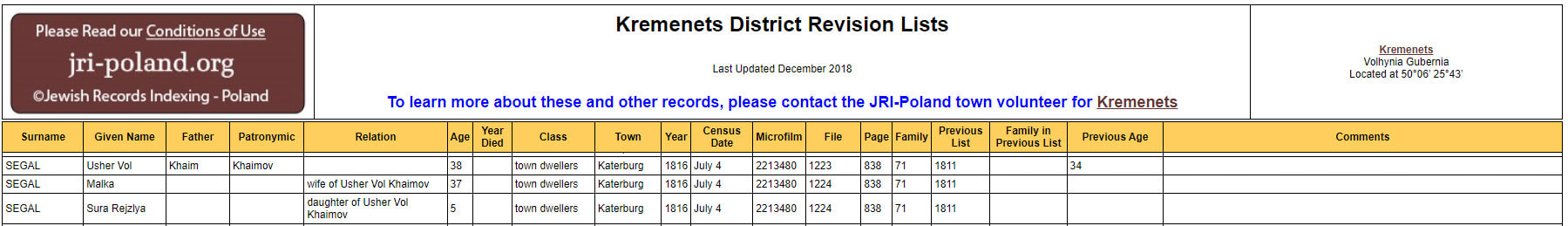

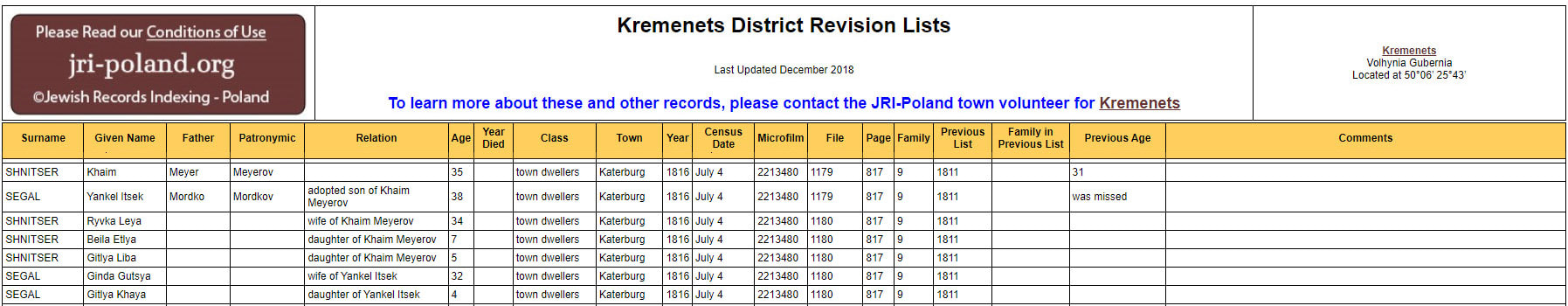

SEGALS FROM KATERINOVKA

MEER SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

OVSHIA SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

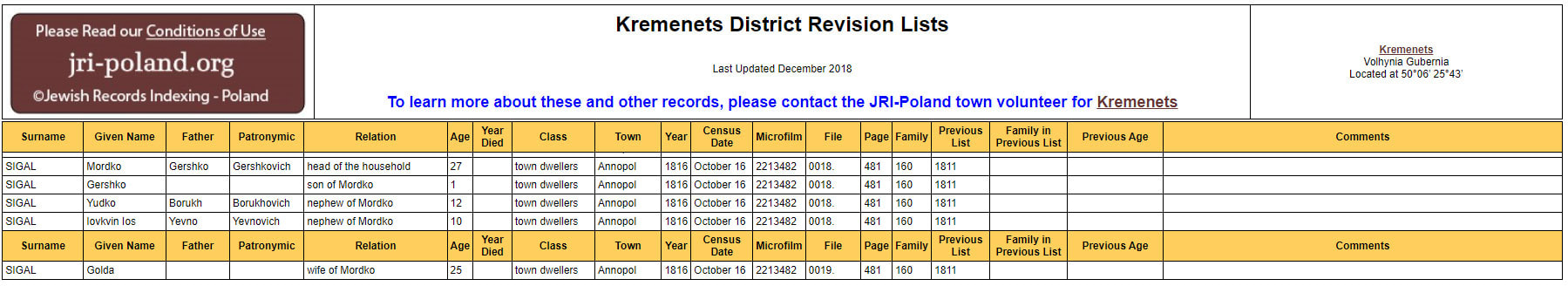

SEGALS FROM ANNOPOL

SHMUL SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

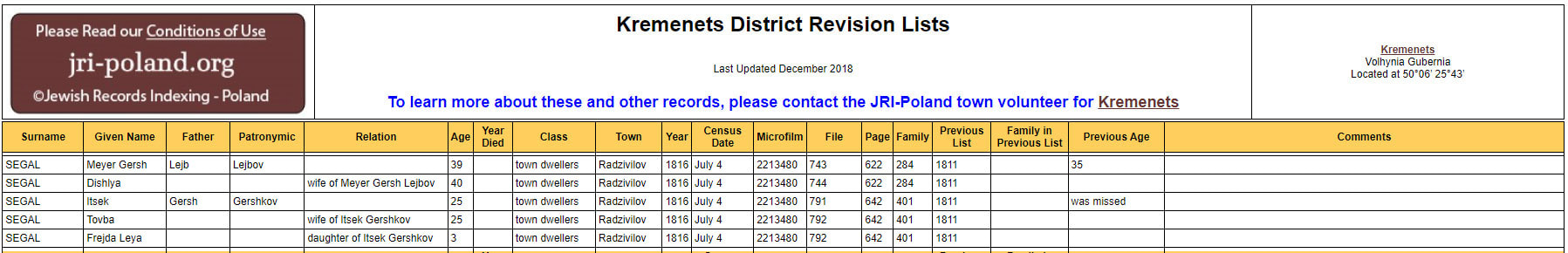

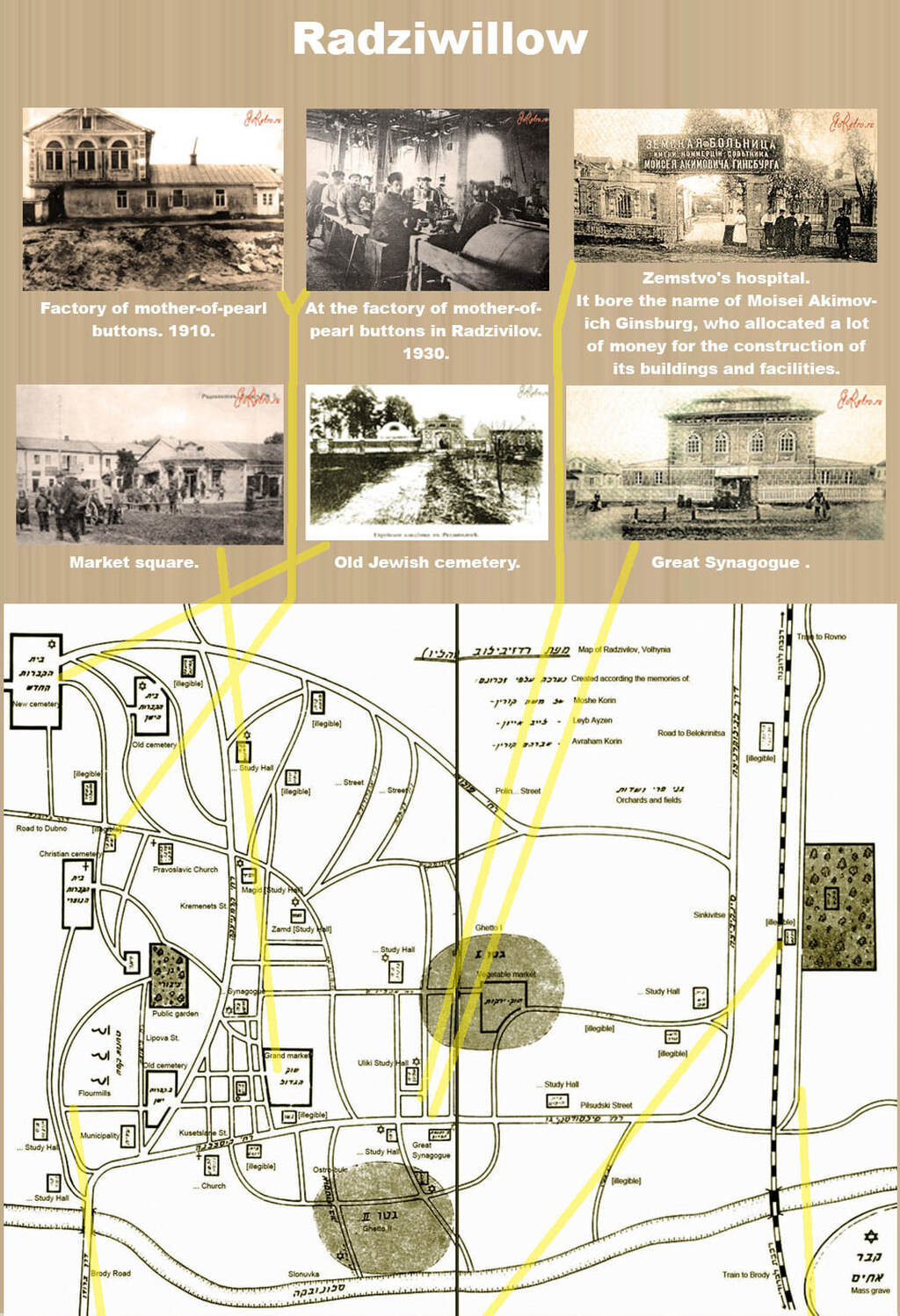

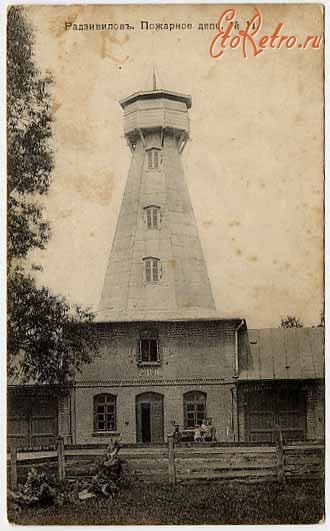

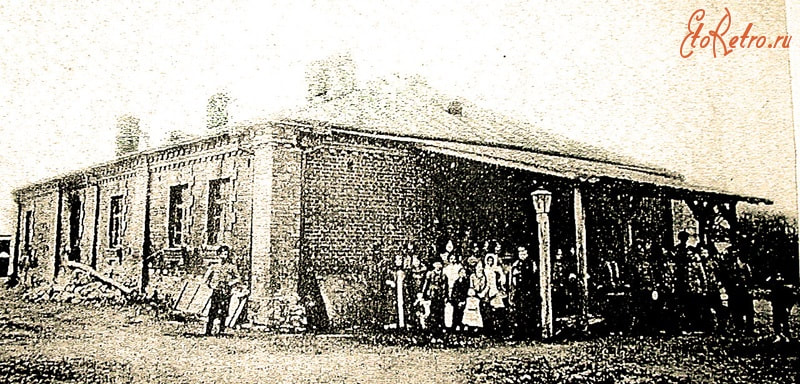

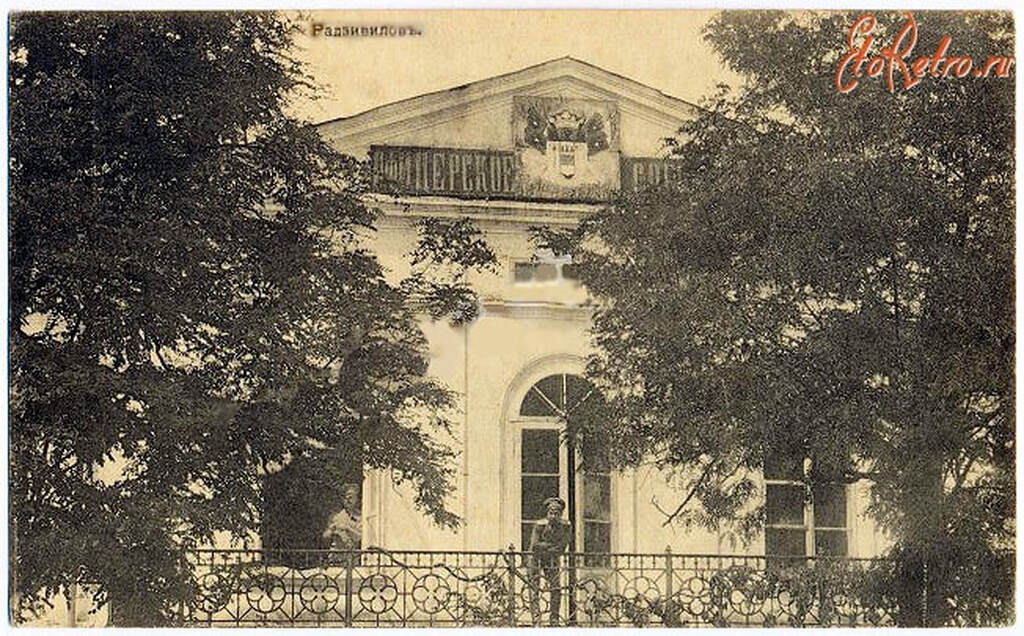

SEGALS FROM RADIVILOV

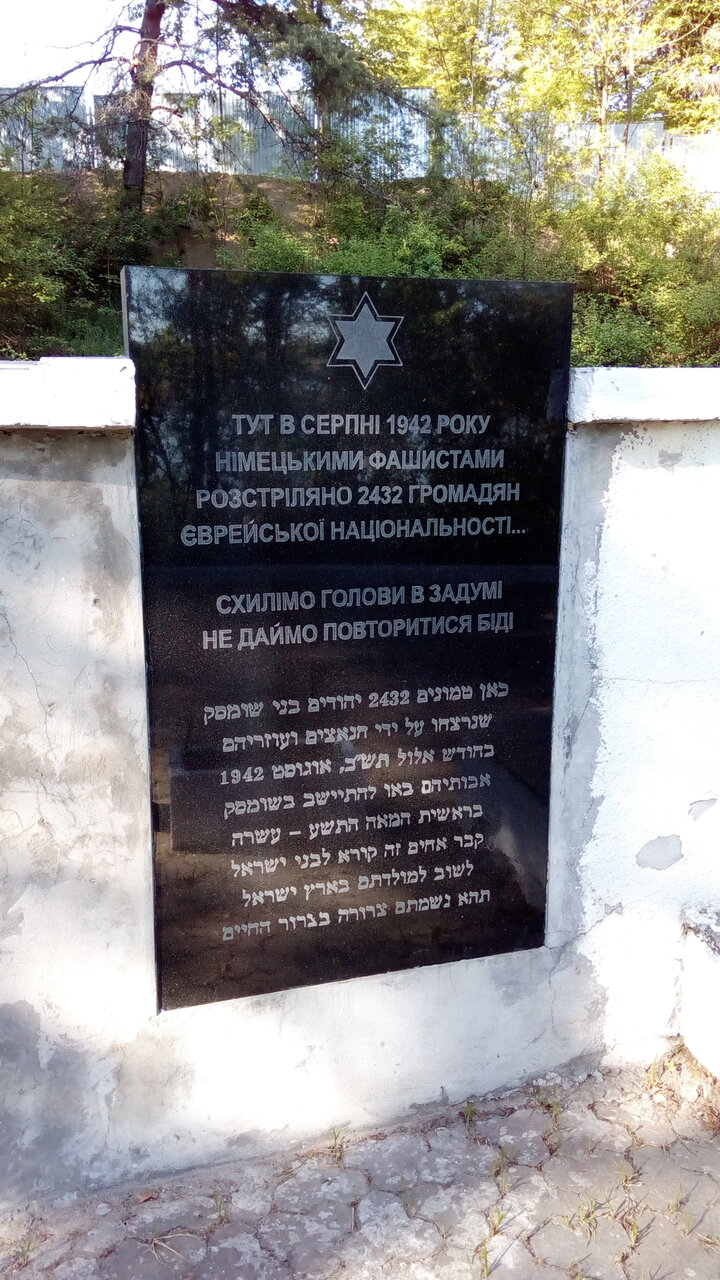

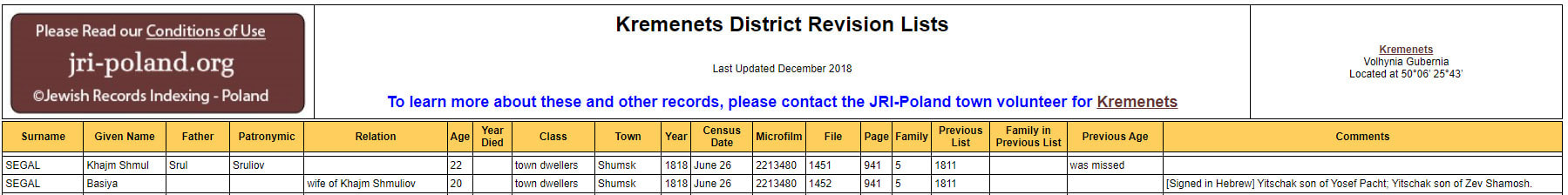

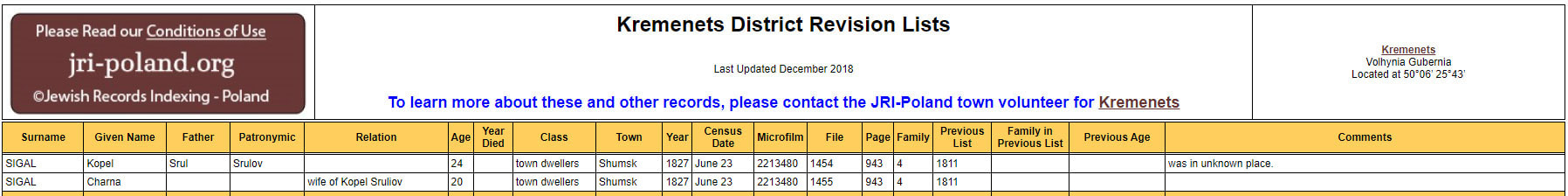

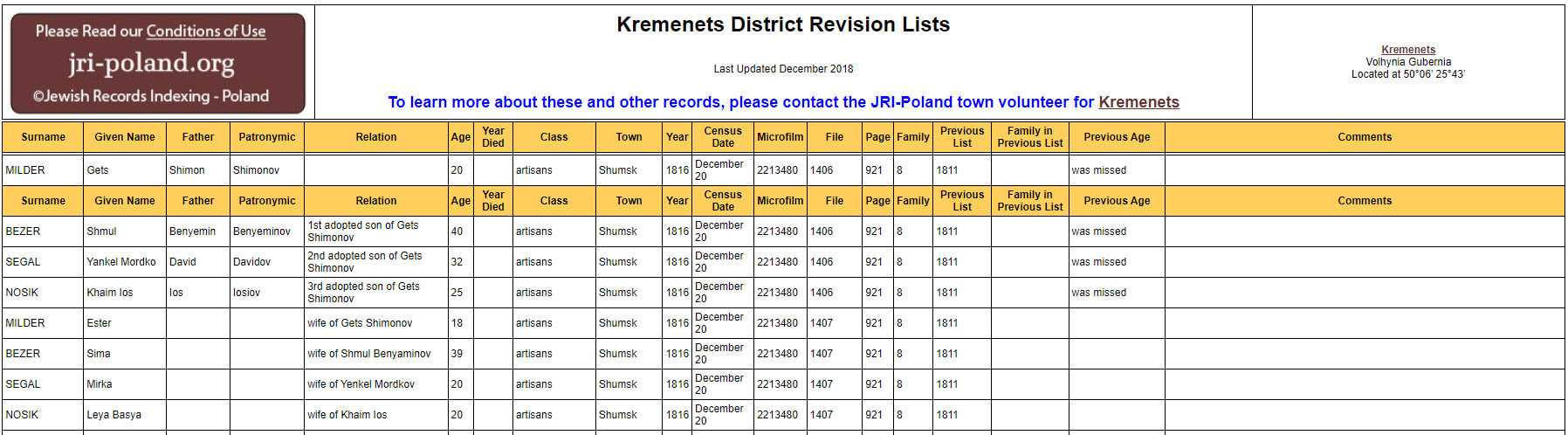

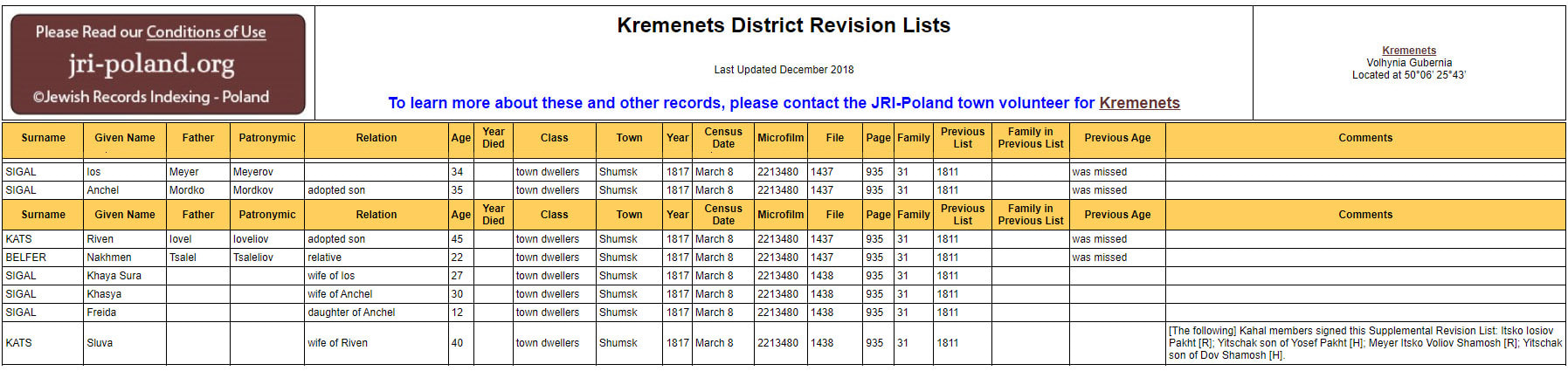

SEGALS FROM SHUMSK

MORDKO SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

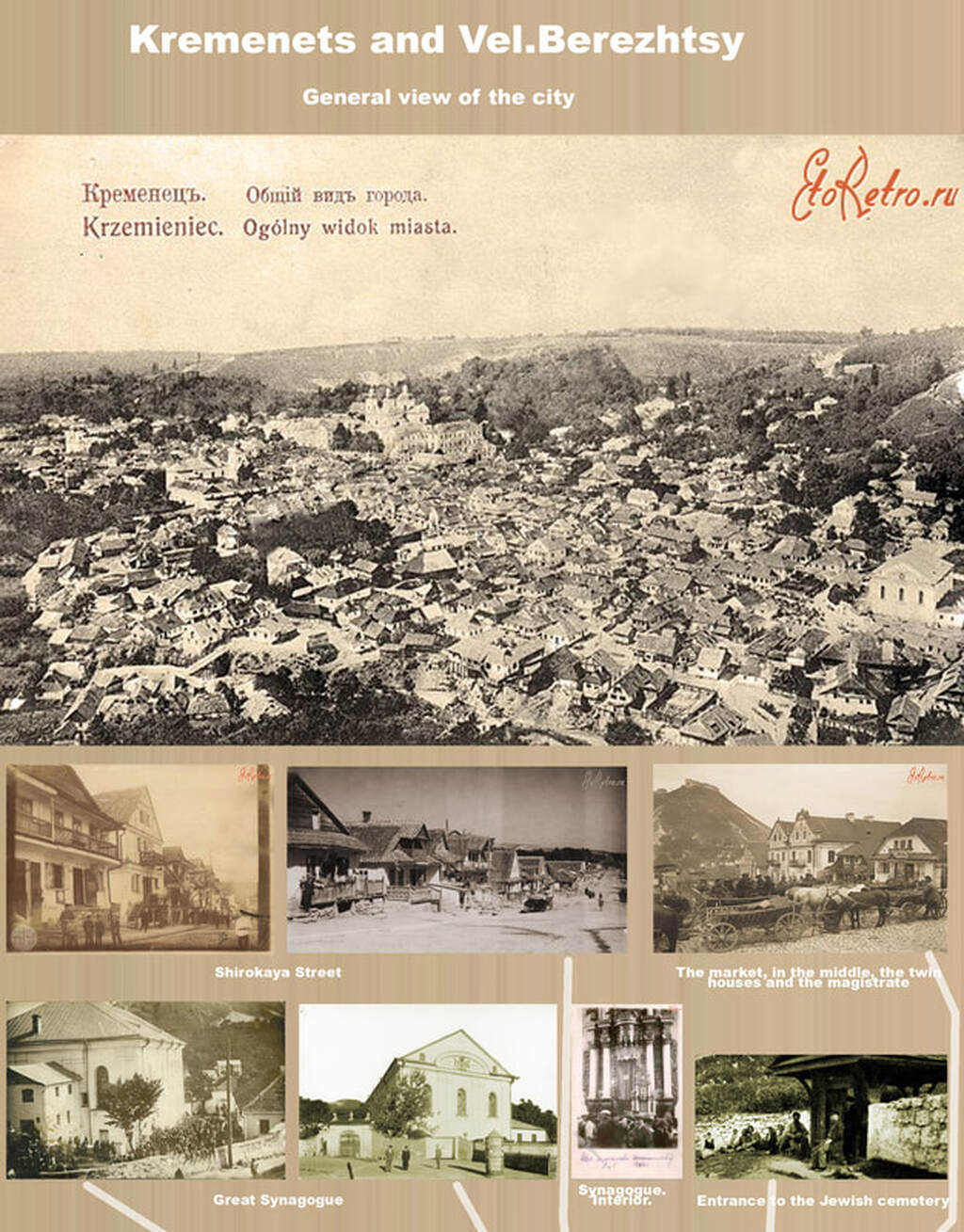

SEGALS FROM KREMENETS

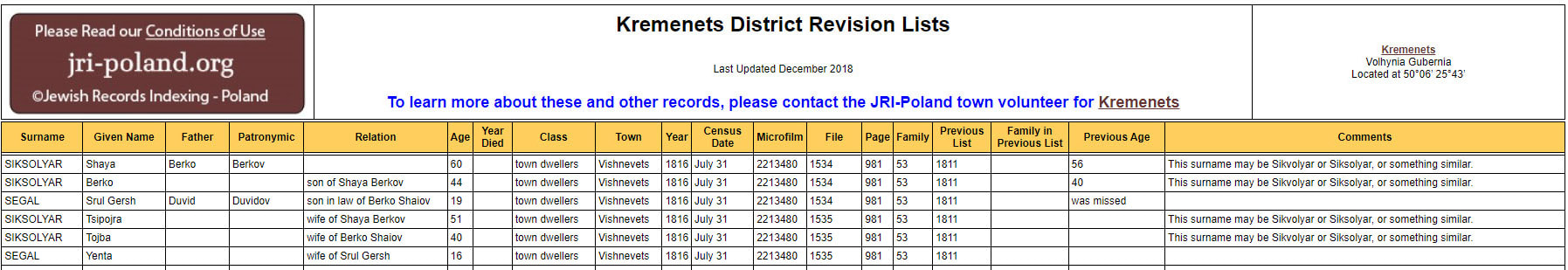

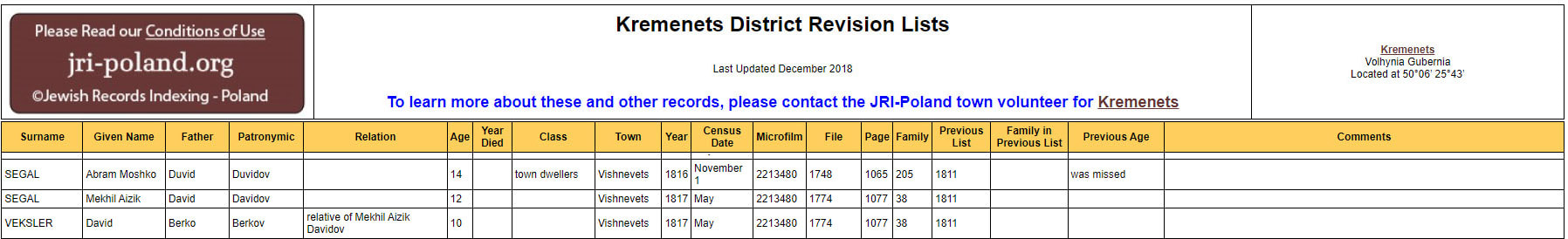

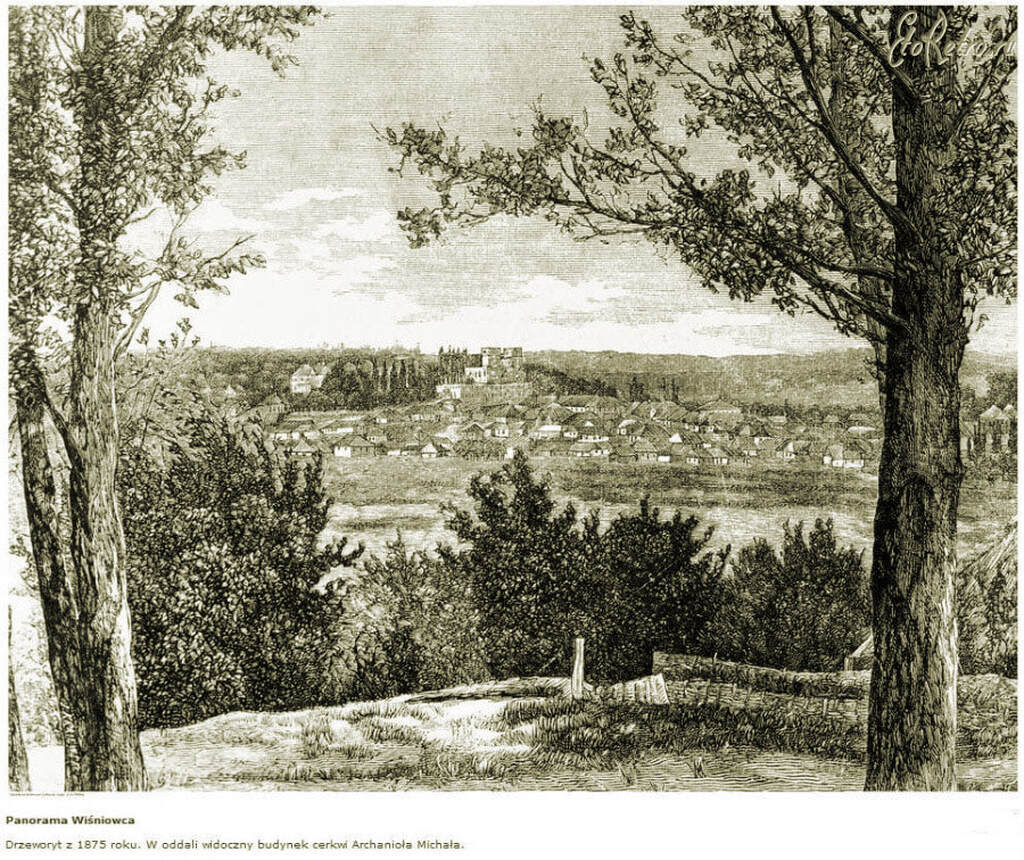

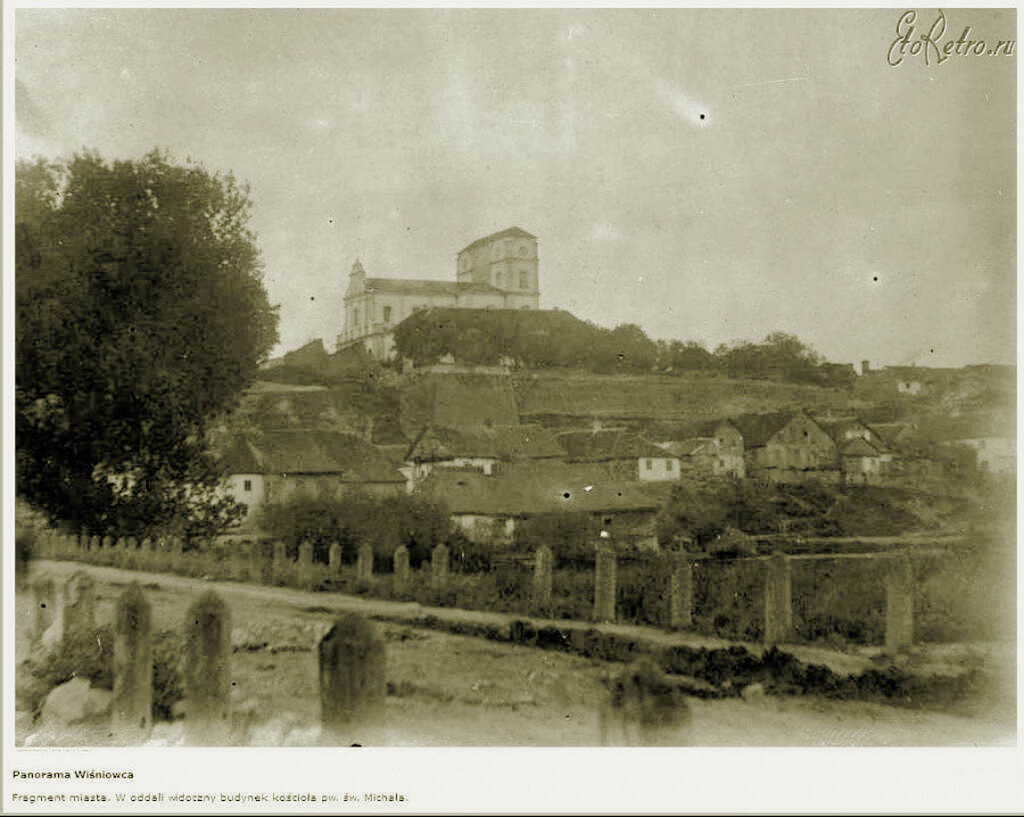

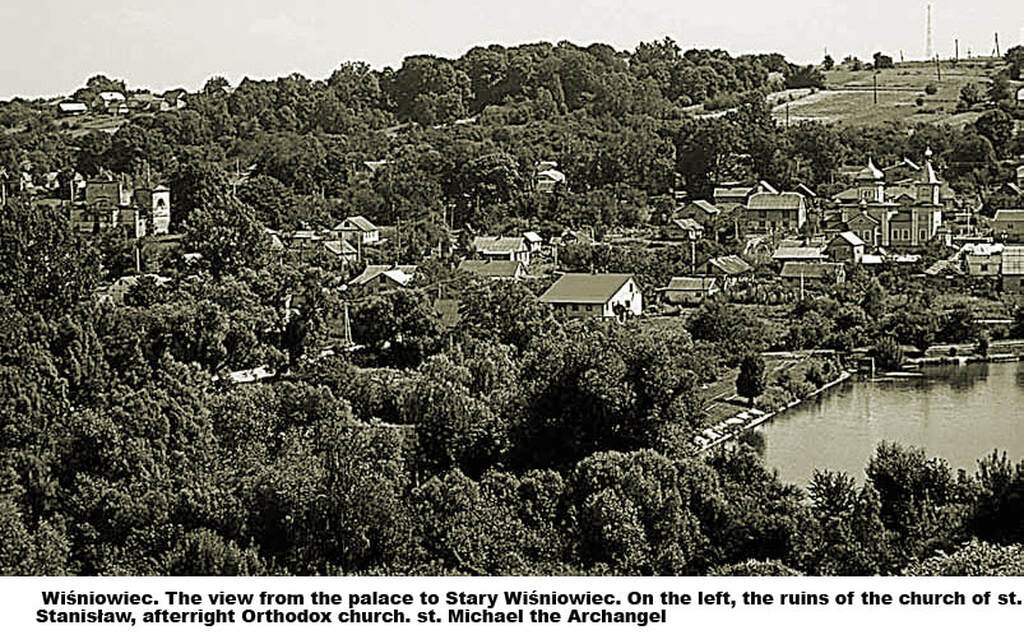

SEGALS FROM VYSHNIVETS

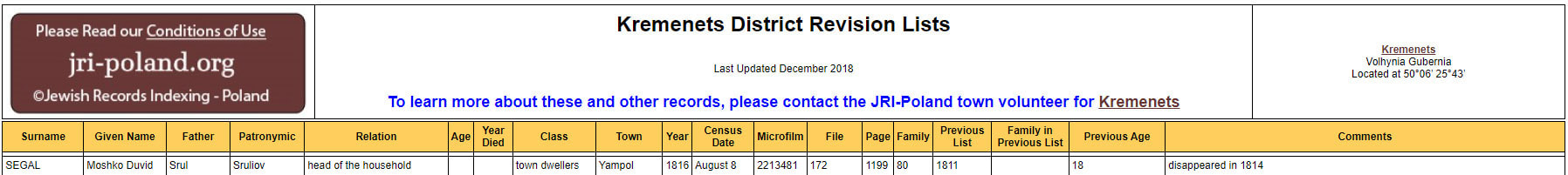

SEGALS FROM YAMPOL

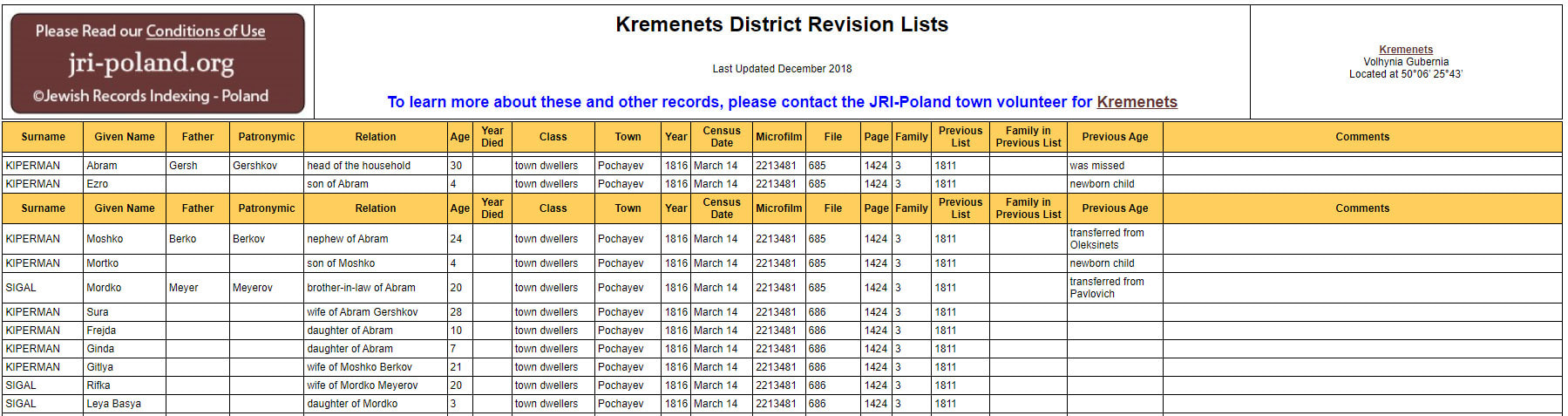

SEGALS FROM POCHAEV

SEGALS FROM VISHGORODOK

MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SHLOMA SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

LEIB SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

KOS SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

BERKO SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

YOS SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

SHIMON SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH, MOSHKO SUB-BRANCH)

DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO

OVSEY BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO)

GERSHKO BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO)

SUB-BRANCHES MOSHKO, LEIBA, ITSKO, BASIA, YANKEL, AVRUMA (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO, GERSHKO BRANCH)

SOKHARA SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO, GERSHKO BRANCH)

DUVID SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF MOSHKO, GERSHKO BRANCH)

DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO

USHER BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO)

VOLKO BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO)

GERSHKO SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

SHENDER SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

MIKHAIL SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

SHLOMO SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, VOLKO BRANCH)

OUR ANCESTORS FROM FASTOV

ABRAM BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO)

LEIB SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

CHASKEL LEYBOVICH FAMILY (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAMA BRANCH, SUB-BRANCH LEIB)

DAVID-MORDUKH YOSELEVICH FAMILY (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH, SUB-BRANCH LEIB)

YOS SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

MOSHKO SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV FAMILY TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

MEER SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

DUVID SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

YANKEL SUB BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF GERSHKO, ABRAM BRANCH)

RADOMYSL

RADOMYSL - BUSINESS PEOPLE IN 1895, 1899, 1913.

OTHER SAGALOV NEAR RADOMYSL

OUR ANCESTORS FROM THE CITY OF RADOMYSL

OUR ANCESTORS FROM THE CITY OF MALIN

THE ORIGIN OF JEWISH NAMES IN OUR FAMILY

SCARY TIMES FOR OUR RADOMYSL ANCESTORS

Segal Additional Records

Content

FAMOUS SCHOLARS

ABRAM SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

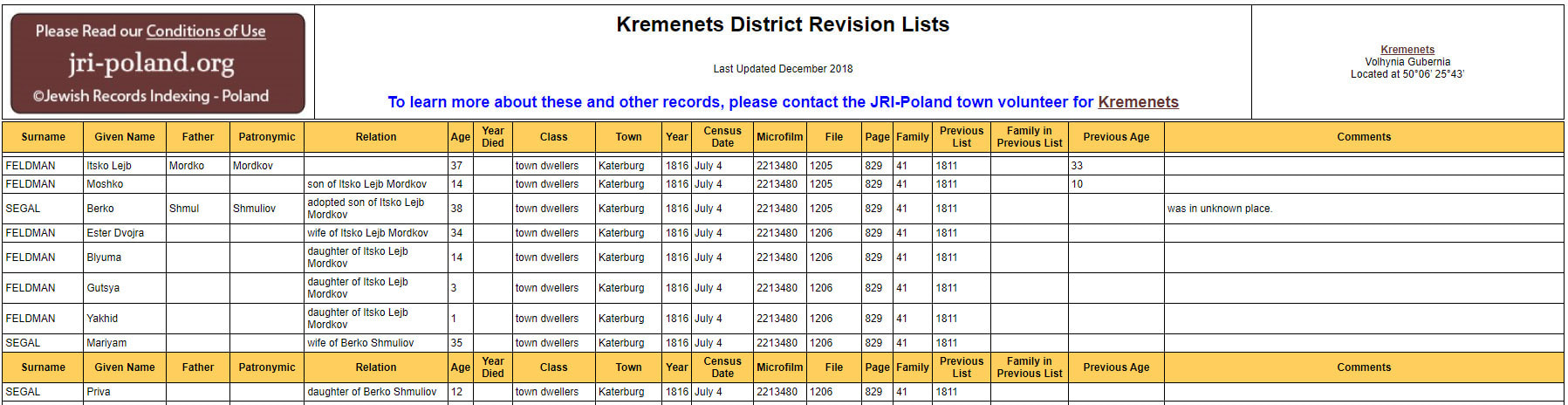

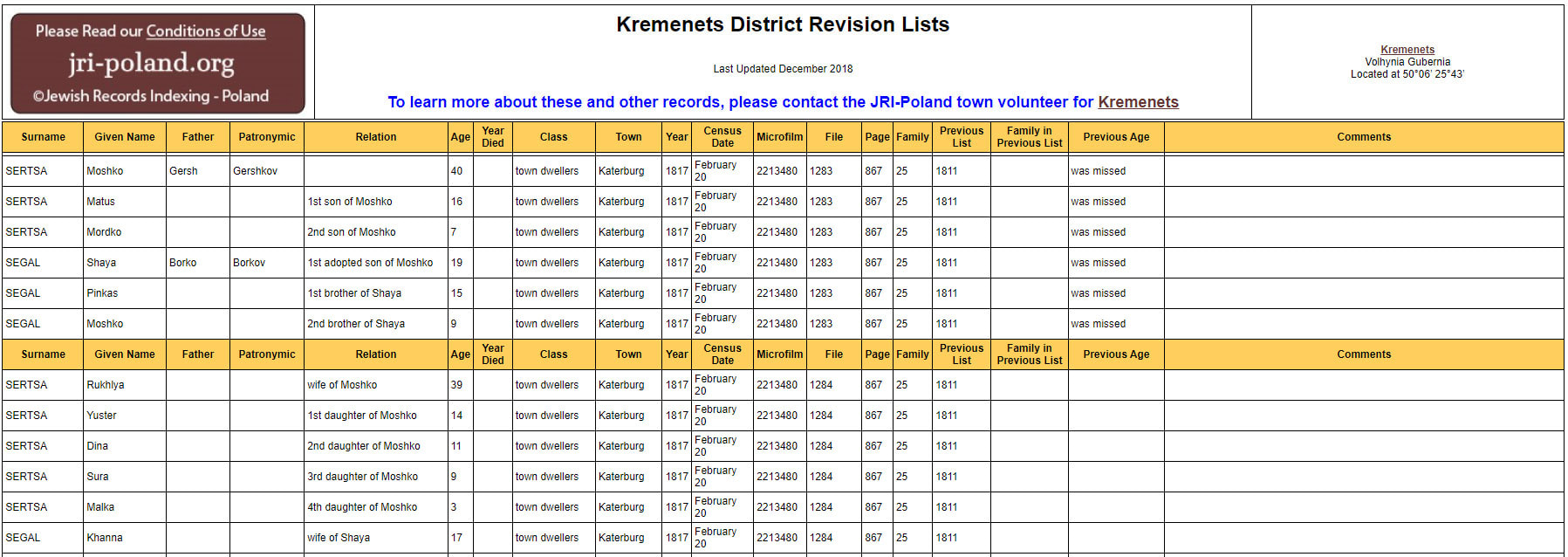

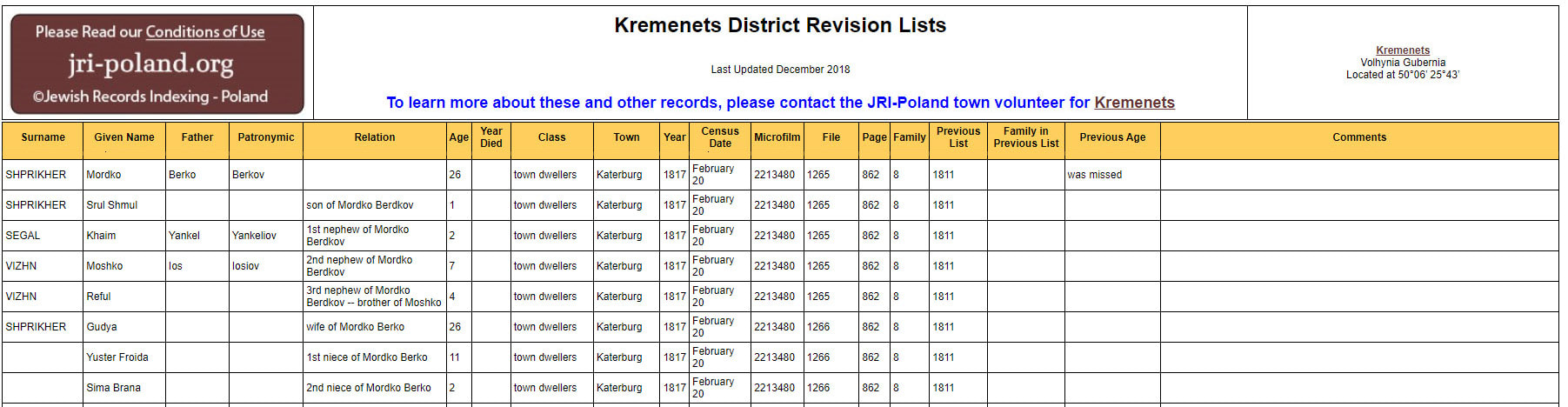

SEGALS FROM KATERINOVKA

MEER SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

OVSHIA SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

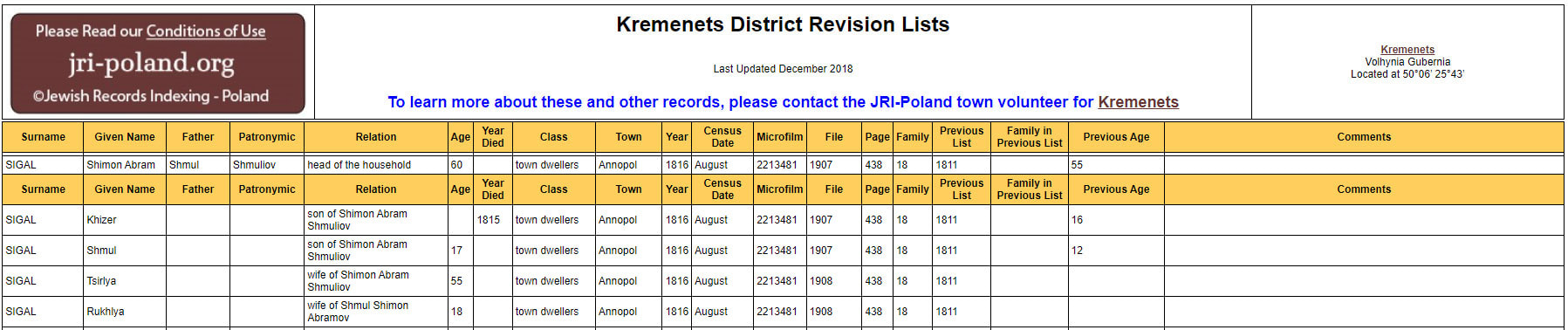

SEGALS FROM ANNOPOL

SHMUL SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

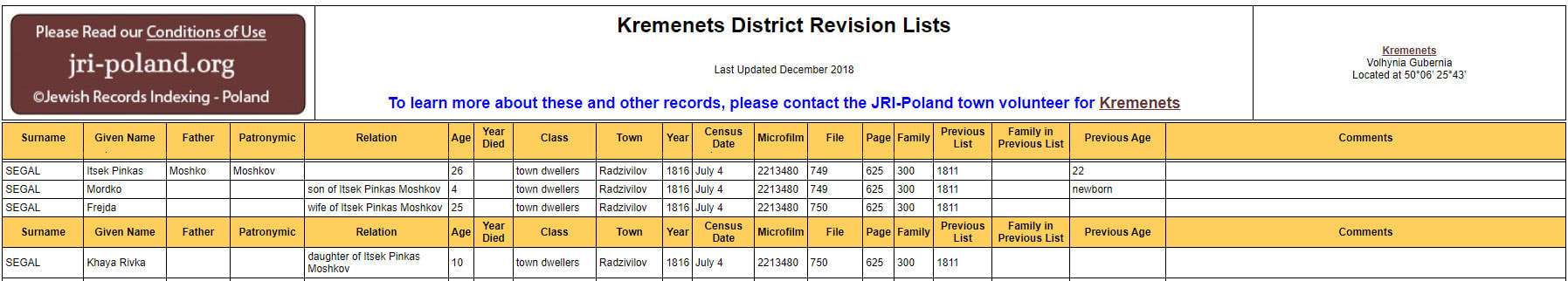

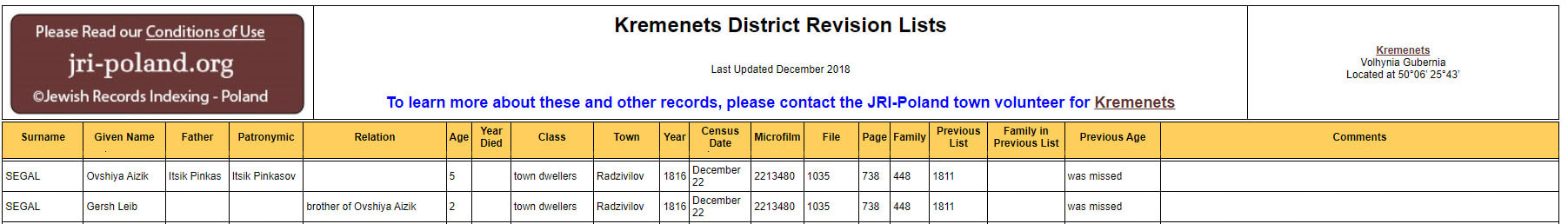

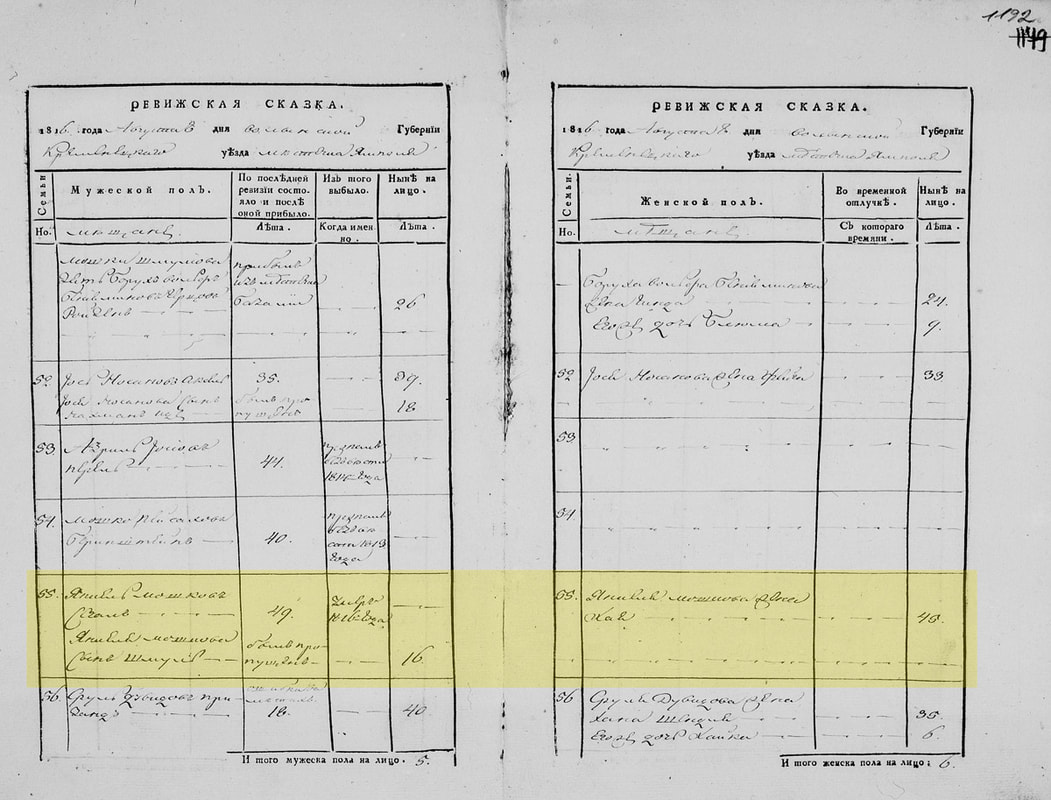

SEGALS FROM RADIVILOV

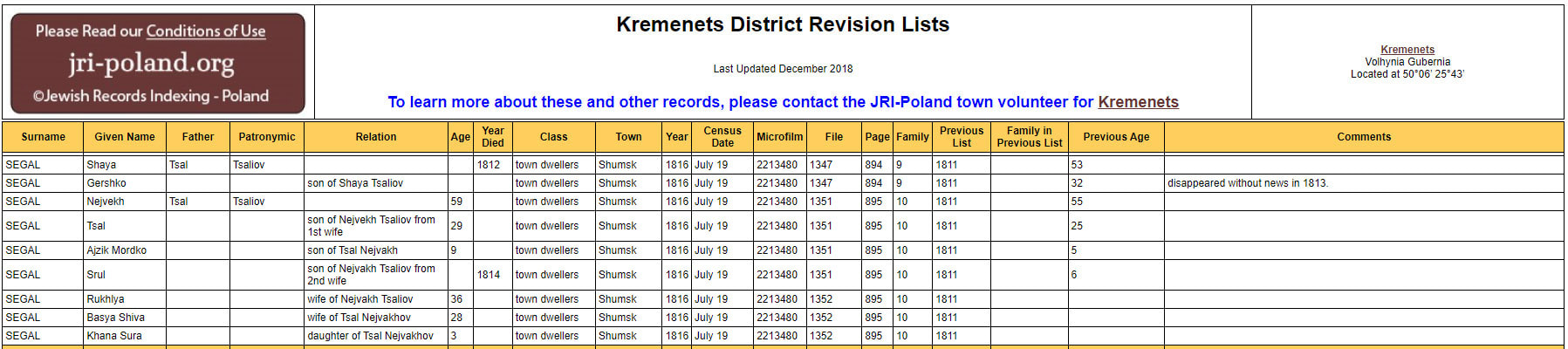

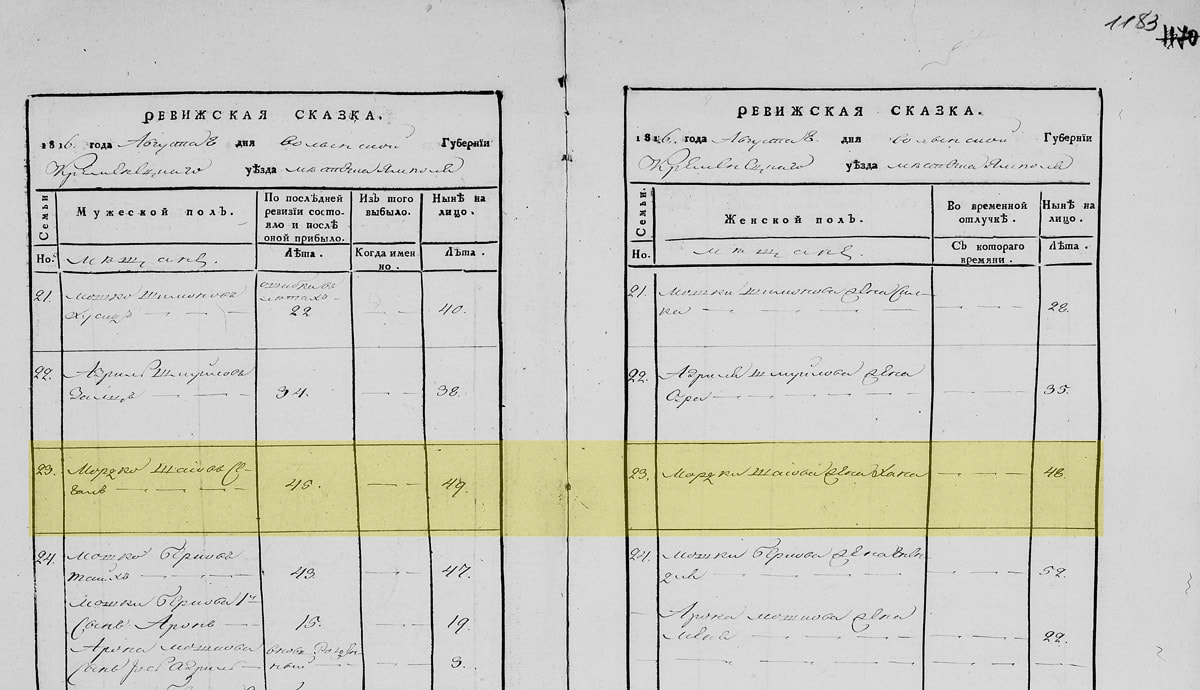

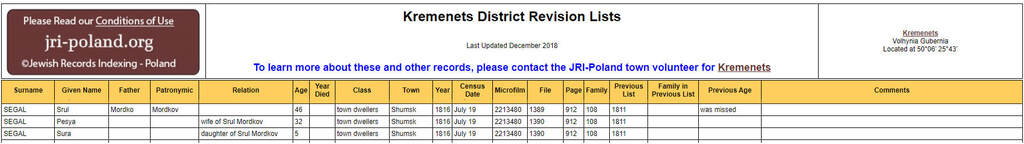

SEGALS FROM SHUMSK

MORDKO SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM KREMENETS

SEGALS FROM VYSHNIVETS

SEGALS FROM YAMPOL

SEGALS FROM POCHAEV

SEGALS FROM VISHGORODOK

FAMOUS SCHOLARS

ABRAM SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM KATERINOVKA

MEER SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

OVSHIA SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM ANNOPOL

SHMUL SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM RADIVILOV

SEGALS FROM SHUMSK

MORDKO SUB-SUB-BRANCH (SAGALOV TREE, DESCENDANTS OF ITSKO-AYZIK, KHAIM BRANCH)

SEGALS FROM KREMENETS

SEGALS FROM VYSHNIVETS

SEGALS FROM YAMPOL

SEGALS FROM POCHAEV

SEGALS FROM VISHGORODOK

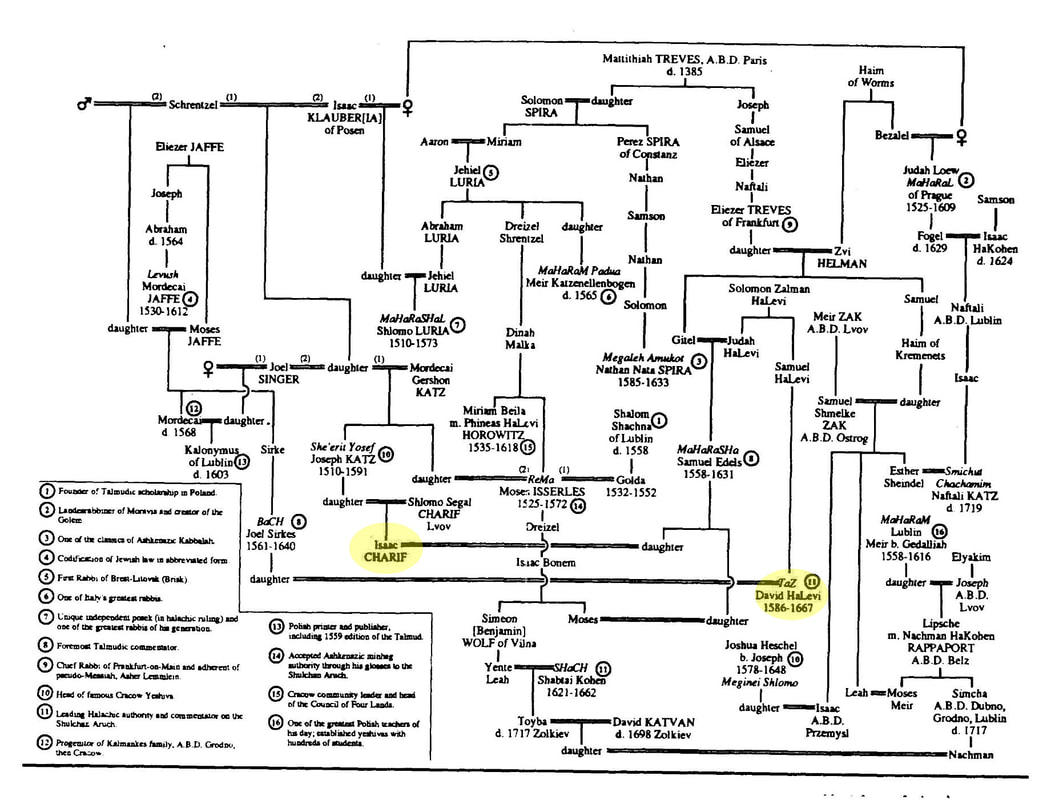

Famous Scholars

During our research on the reconstruction of our family trees, we came across stories about the founders of the Talmudic scholarship of the 13th - 16th centuries in Poland. A lot of them were Levites (Halevi/Segal). Below are descriptions of the Segals we came across.

Founders of the Talmudic scholarship of the 13th - 16th centuries in Poland

Rabbi David ben Shmuel Segal Halevi – the Taz

(5346-5427; 1586-1667)

Rabbi David ben Shmuel Segal Halevi – the Taz

(5346-5427; 1586-1667)

Rabbi David ben Shmuel Segal Halevi – the Taz

(5346-5427; 1586-1667)

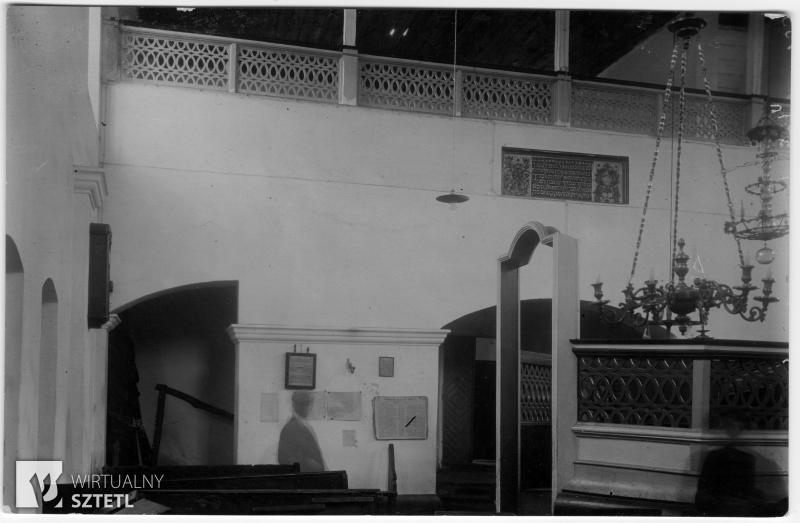

Rabbi David Halevi, better known as the TaZ, after the initials of his main work Turei Zahav ("Rows of Gold"), was born in Vladomir, in the Province of Volhynia. His family was famed for scholarship. His father Samuel was the son of a famous scholar Rabbi Isaac Betzalels. In addition to his scholarship, David's father was well to do, so that the young prodigy David, who had shown unusual talent for study, was fortunate enough to grow up in an atmosphere of both wealth and learning. His early, happy youth was in marked contrast to his later years, when he suffered great hardships and poverty, as we shall see later.

The young David was fortunate also in another way. He had an older half-brother called Rabbi Isaac Halevi (Charif), a great Talmud scholar who founded Yeshivoth in Vladomir, Chelm and Lvow Poland, and was the author of two books on Hebrew grammar, called "Siach Yitzchak," and "Brith Halevi." This great man dearly loved his younger brother, and became his first teacher and counsellor for many years. The affection between the two brothers never diminished in later years, and they continued to correspond with each other in writing after they had been separated. A part of this correspondence has been preserved. These letters are of great interest not only because they testify to the deep friendship and love that existed between the two brothers, but also because they contain an exchange of scholarly opinions on many problems of Jewish law.

Rabbi Isaac Halevi did not fail to recognize his younger brother's mental abilities, and did his best to encourage his literary work, which became indeed a masterpiece in the world of Halachah (Jewish law).

The young scholar married the daughter of no less famous a man than he himself later became. Rabbi David Halevi's father-in-law was Rabbi Joel Sirkes, known as the BaCH, after the initials of his commentary on the Turint entitled "Bayith Chadash" (New House). As was customary in those days, Rabbi David stayed in his father-in-law's house for several years, during which be applied himself fully to the study of the Talmud and Posekim (codifiers). This period served him as a good preparation for the great contribution which he himself was to make to this immense literature.

ii.

After Rabbi David Halevi left his father-in-law's house to make a home of his own, he accepted the position of rabbi in a small town, a position he changed several times for other small towns. During this time he suffered poverty and want, and was stricken by other misfortunes also. Several of his children died in infancy. (Many years later, towards the end of his life, two more sons of Rabbi David Halevi, who were famous scholars, were killed in a massacre in Lemberg in 1664). However, in due course Rabbi David had made a name for himself, and he was invited to become the Rabbi of the famed city of scholars-Ostrog. This was in the year 1641, and since then his poverty gave way to a life of comfort, as he had earned the recognition and respect due him. Here Rabbi David Halevi founded his own Yeshivah, but he found time also for his literary work. The leaders of this great Jewish community, many of whom were scholars of high standing, did everything in their power to help their great rabbi in his gigantic work. It was due to their influence and active cooperation that Rabbi David Halevi, by nature a shy and modest man, wrote his commentary on the first two volumes of the Shulchan Aruch, the Yoreh Deah and Orach Chaim. "Turei Zahav" was the name given to this important work, or TaZ for short.

Rabbi David Halevi's work soon won world-wide recognition and established his name among the greatest Talmudists of his day. It so happened that in the same year (5406-1646) when Rabbi David Halevi published his work, another scholarly giant, Rabbi Shabbatai Cohen of Vilna, published a similar commentary on the Yoreh Deah, entitled "Sifesei Cohen," (Lips of a Cohen), and soon became equally famous by the name "ShaCh." However, neither detracted from the fame of the other, and far from there arising any jealousy between them, they became the best of friends, although they often had conflicting opinions as to interpreting the decisions of their master, Rabbi Joseph Caro. Several years after their commentaries had first been printed, they cooperated in the publication of an edition of the Yoreh Deah, in which the text of the author Rabbi Joseph Caro was printed in the center of the page, flanked on one side by the "TaZ" and on the other by the "ShaCH." (This edition of Yoreh Deah was called "Ashrei Ravrevi.") This edition was later enlarged by the addition of other commentaries, but the form given to the Yoreh Deah by the two great commentators became the standard type for further reprintings of this book of laws over and over again, to this day.

The TaZ's commentary on the Orach Chaim was acclaimed with equal enthusiasm. It was later published in a special edition of this part of the Shulhban Aruch, similar to the above, except that here his companion-commentator was Rabbi Abraham Avlei Gumbiner, Dayan of the city of Kalish. The commentary by the latter was called "Magen Avraham," while his own was entitled "Magen David." The edition of this volume was therefore called "Maginei Eretz," (Shields of the Land). It was published by the son of Rabbi Abraham Gumbiner. This edition became the most popular book of Jewish law, inasmuch as it deals with the general aspects of Jewish daily life, while the other parts of the Shulchan Aruch deal with special subjects, such as laws of Shechitah and Kashruth, claims and damages, marriage and divorce, etc. The popularity of this volume has not diminished during the years; its influence on the preservation of Jewish traditional life has been immense. It is now as widely used and studied as ever, thus bringing immortality to three men who were responsible for it.

iii.

Rabbi David Halevi's happy period of teaching and writing in Ostrog was rudely interrupted by the cruel massacre by the inhuman Cossacks under the leadership of Chmielnicki, who led his revolt against the Polish nobility and at the same time massacred and pillaged all Jewish communities that fell into his hands. Rabbi David Halevi was fortunate enough to flee from Ostrog before it was captured by the Cossacks. He succeeded in saving also his priceless manuscripts. He was then invited to become rabbi of Lvov (Lemberg), where he continued his work to spread the knowledge of the Torah. A cruel blow was struck at the aged Rabbi David Halevi when three years before his death he lost his two older sons, Rabbi Mordecai and Rabbi Solomon Halevi, who were murdered in a pogrom in Lemberg.

Rabbi David Halevi died at the age of 81.

The lifework of this modest man and the influence of his masterpieces can hardly be appraised properly. His contribution to the tradition of the world of Halachah puts him among the greatest of our illustrious Talmudists. The TaZ is also the author of a commentary on Rashi, entitled Divre David-the Words of David-and of other works. As commentator and teacher, he accomplished great feats for the education of the Jewish people in the spirit and the knowledge of the Torah and its literature. As community leader he founded Yeshivoth, gave counsel and advice, and did his share in the violent fight against the dangerous movement of Shabbathai Tzvi's followers who threatened to undermine the basis of the Jewish law and belief. Both in his literary work and in his activities he created a strong fortress against attacks from within and without. There is no greater praise for Rabbi David Halevi, than the tribute given to him by his beloved brother and teacher, Rabbi Yitzchok Halevi who said of the TaZ: "Rabbi David Halevi's name spread over all countries and G‑d helped his work to worldwide recognition and acceptance... His heart was pure and candid as the heavens; his words were divine in their clarity and lucidity, despite their modest and pious presentation." No greater tribute could have been given to a great man.

The young David was fortunate also in another way. He had an older half-brother called Rabbi Isaac Halevi (Charif), a great Talmud scholar who founded Yeshivoth in Vladomir, Chelm and Lvow Poland, and was the author of two books on Hebrew grammar, called "Siach Yitzchak," and "Brith Halevi." This great man dearly loved his younger brother, and became his first teacher and counsellor for many years. The affection between the two brothers never diminished in later years, and they continued to correspond with each other in writing after they had been separated. A part of this correspondence has been preserved. These letters are of great interest not only because they testify to the deep friendship and love that existed between the two brothers, but also because they contain an exchange of scholarly opinions on many problems of Jewish law.

Rabbi Isaac Halevi did not fail to recognize his younger brother's mental abilities, and did his best to encourage his literary work, which became indeed a masterpiece in the world of Halachah (Jewish law).

The young scholar married the daughter of no less famous a man than he himself later became. Rabbi David Halevi's father-in-law was Rabbi Joel Sirkes, known as the BaCH, after the initials of his commentary on the Turint entitled "Bayith Chadash" (New House). As was customary in those days, Rabbi David stayed in his father-in-law's house for several years, during which be applied himself fully to the study of the Talmud and Posekim (codifiers). This period served him as a good preparation for the great contribution which he himself was to make to this immense literature.

ii.

After Rabbi David Halevi left his father-in-law's house to make a home of his own, he accepted the position of rabbi in a small town, a position he changed several times for other small towns. During this time he suffered poverty and want, and was stricken by other misfortunes also. Several of his children died in infancy. (Many years later, towards the end of his life, two more sons of Rabbi David Halevi, who were famous scholars, were killed in a massacre in Lemberg in 1664). However, in due course Rabbi David had made a name for himself, and he was invited to become the Rabbi of the famed city of scholars-Ostrog. This was in the year 1641, and since then his poverty gave way to a life of comfort, as he had earned the recognition and respect due him. Here Rabbi David Halevi founded his own Yeshivah, but he found time also for his literary work. The leaders of this great Jewish community, many of whom were scholars of high standing, did everything in their power to help their great rabbi in his gigantic work. It was due to their influence and active cooperation that Rabbi David Halevi, by nature a shy and modest man, wrote his commentary on the first two volumes of the Shulchan Aruch, the Yoreh Deah and Orach Chaim. "Turei Zahav" was the name given to this important work, or TaZ for short.

Rabbi David Halevi's work soon won world-wide recognition and established his name among the greatest Talmudists of his day. It so happened that in the same year (5406-1646) when Rabbi David Halevi published his work, another scholarly giant, Rabbi Shabbatai Cohen of Vilna, published a similar commentary on the Yoreh Deah, entitled "Sifesei Cohen," (Lips of a Cohen), and soon became equally famous by the name "ShaCh." However, neither detracted from the fame of the other, and far from there arising any jealousy between them, they became the best of friends, although they often had conflicting opinions as to interpreting the decisions of their master, Rabbi Joseph Caro. Several years after their commentaries had first been printed, they cooperated in the publication of an edition of the Yoreh Deah, in which the text of the author Rabbi Joseph Caro was printed in the center of the page, flanked on one side by the "TaZ" and on the other by the "ShaCH." (This edition of Yoreh Deah was called "Ashrei Ravrevi.") This edition was later enlarged by the addition of other commentaries, but the form given to the Yoreh Deah by the two great commentators became the standard type for further reprintings of this book of laws over and over again, to this day.

The TaZ's commentary on the Orach Chaim was acclaimed with equal enthusiasm. It was later published in a special edition of this part of the Shulhban Aruch, similar to the above, except that here his companion-commentator was Rabbi Abraham Avlei Gumbiner, Dayan of the city of Kalish. The commentary by the latter was called "Magen Avraham," while his own was entitled "Magen David." The edition of this volume was therefore called "Maginei Eretz," (Shields of the Land). It was published by the son of Rabbi Abraham Gumbiner. This edition became the most popular book of Jewish law, inasmuch as it deals with the general aspects of Jewish daily life, while the other parts of the Shulchan Aruch deal with special subjects, such as laws of Shechitah and Kashruth, claims and damages, marriage and divorce, etc. The popularity of this volume has not diminished during the years; its influence on the preservation of Jewish traditional life has been immense. It is now as widely used and studied as ever, thus bringing immortality to three men who were responsible for it.

iii.

Rabbi David Halevi's happy period of teaching and writing in Ostrog was rudely interrupted by the cruel massacre by the inhuman Cossacks under the leadership of Chmielnicki, who led his revolt against the Polish nobility and at the same time massacred and pillaged all Jewish communities that fell into his hands. Rabbi David Halevi was fortunate enough to flee from Ostrog before it was captured by the Cossacks. He succeeded in saving also his priceless manuscripts. He was then invited to become rabbi of Lvov (Lemberg), where he continued his work to spread the knowledge of the Torah. A cruel blow was struck at the aged Rabbi David Halevi when three years before his death he lost his two older sons, Rabbi Mordecai and Rabbi Solomon Halevi, who were murdered in a pogrom in Lemberg.

Rabbi David Halevi died at the age of 81.

The lifework of this modest man and the influence of his masterpieces can hardly be appraised properly. His contribution to the tradition of the world of Halachah puts him among the greatest of our illustrious Talmudists. The TaZ is also the author of a commentary on Rashi, entitled Divre David-the Words of David-and of other works. As commentator and teacher, he accomplished great feats for the education of the Jewish people in the spirit and the knowledge of the Torah and its literature. As community leader he founded Yeshivoth, gave counsel and advice, and did his share in the violent fight against the dangerous movement of Shabbathai Tzvi's followers who threatened to undermine the basis of the Jewish law and belief. Both in his literary work and in his activities he created a strong fortress against attacks from within and without. There is no greater praise for Rabbi David Halevi, than the tribute given to him by his beloved brother and teacher, Rabbi Yitzchok Halevi who said of the TaZ: "Rabbi David Halevi's name spread over all countries and G‑d helped his work to worldwide recognition and acceptance... His heart was pure and candid as the heavens; his words were divine in their clarity and lucidity, despite their modest and pious presentation." No greater tribute could have been given to a great man.

SEGAL, DAVID HALEVI

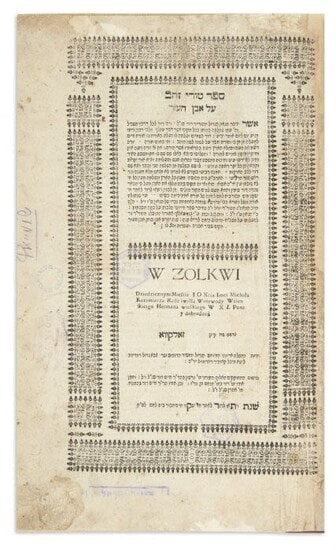

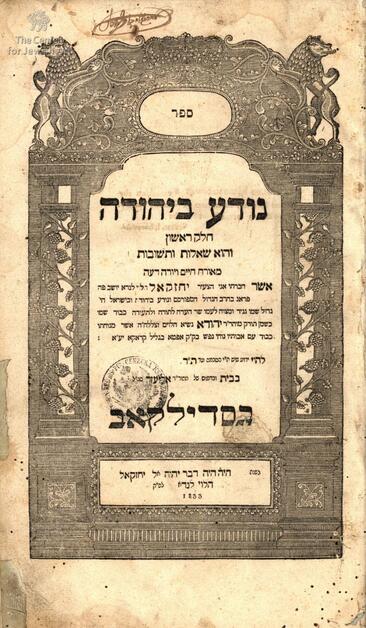

Turei Zahav [an indispensable commentary to Shulchan Aruch - Even Ha’Ezer].

FIRST EDITION. With approbation by the Noda BeYehudah.

ff. 15, (110) mispaginated. Ex-library, few marginal repairs, browned and stained in places. Modern calf-backed boards. Foloo. Vinograd, Zolkiew 195.

Zolkiew: Gershon ben Chaim David Segal et al 1754

Although Turei Zahav on Orach Chaim is the author’s most celebrated work, he was one of very few to write a thorough commentary on all four sections of the Shulchan Aruch. This portion on Even Ha’Ezer was the last to be brought to the press. David HaLevi Segal (1586-1667), known as the Turei Zahav (also abbreviated to TaZ) after the title of this significant halachic commentary, came to be recognized as one of the great rabbinic authorities of his time.

Turei Zahav [an indispensable commentary to Shulchan Aruch - Even Ha’Ezer].

FIRST EDITION. With approbation by the Noda BeYehudah.

ff. 15, (110) mispaginated. Ex-library, few marginal repairs, browned and stained in places. Modern calf-backed boards. Foloo. Vinograd, Zolkiew 195.

Zolkiew: Gershon ben Chaim David Segal et al 1754

Although Turei Zahav on Orach Chaim is the author’s most celebrated work, he was one of very few to write a thorough commentary on all four sections of the Shulchan Aruch. This portion on Even Ha’Ezer was the last to be brought to the press. David HaLevi Segal (1586-1667), known as the Turei Zahav (also abbreviated to TaZ) after the title of this significant halachic commentary, came to be recognized as one of the great rabbinic authorities of his time.

Rabbi Yechezkel HaLevi (Segal) Landau

(8 October 1713 – 29 April 1793)

Rabbi Yechezkel HaLevi (Segal) Landau

Rabbi Yechezkel HaLevi (Segal) Landau

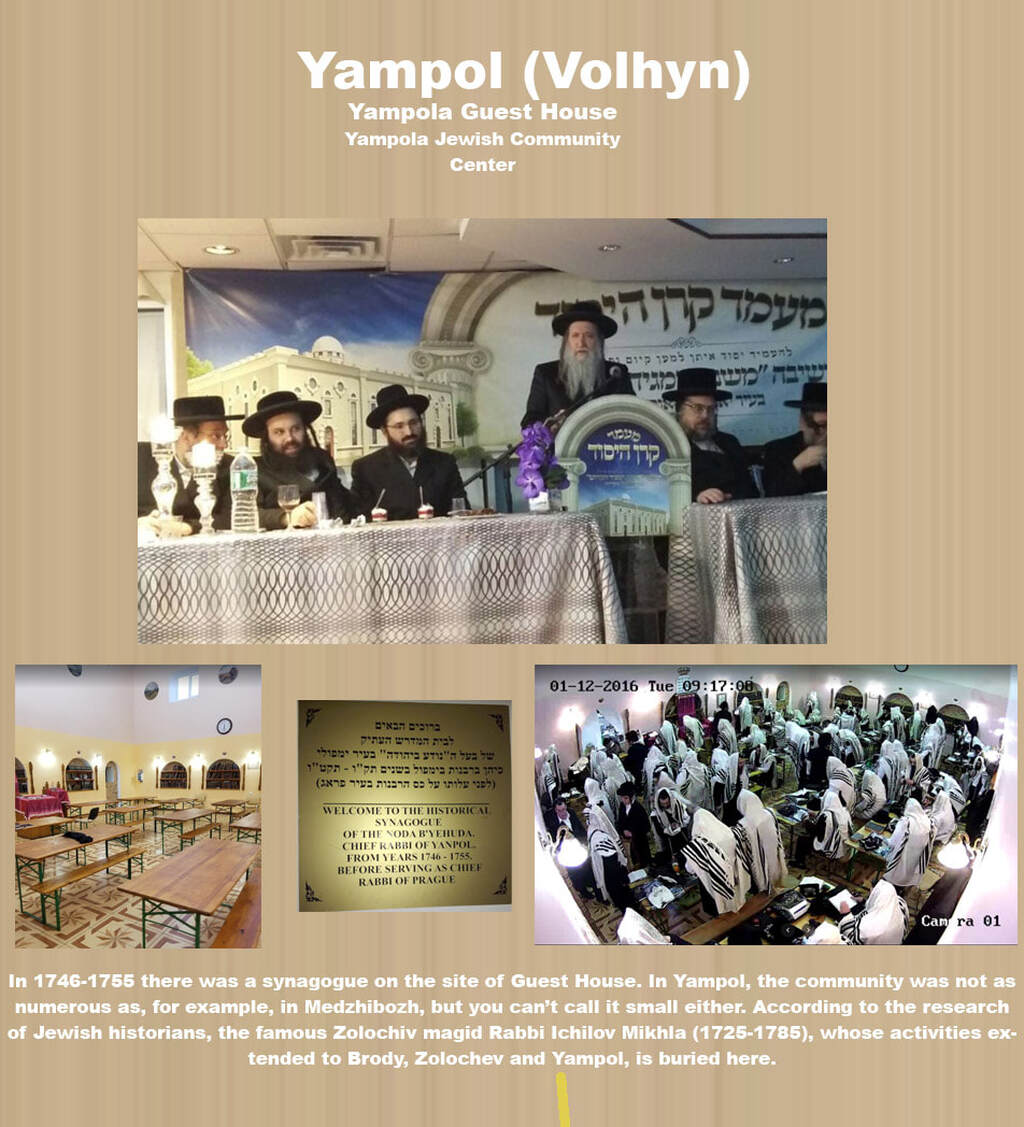

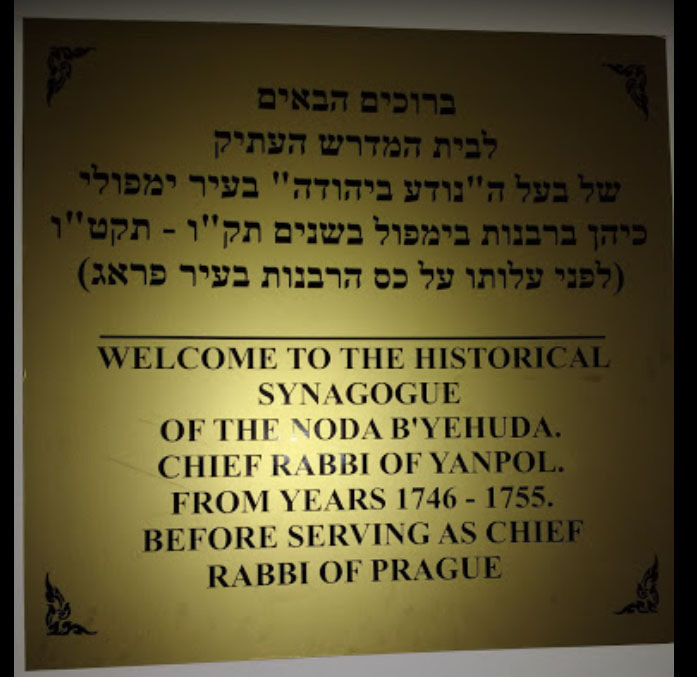

Most of my information about Rav Landau comes from the introductions to the second volume of Noda B’Yehuda, by his sons, Rav Shmuel, the editor, and Yaakovka, who encouraged the project and wrote a longer piece. Yechezkel Landau was born in Apta in 1713, to Yehuda, a wealthy, scholarly businessman, and Chaya, the saintly daughter of the chief rabbi of Dubnow. In Rav Yechezkel’s own introduction to the first volume, he thanks Rav Yitzchak Isaac Segal, his teacher from age 11 to 13. During his adolescence, he moved to Brody to study there. By the age of 20 or so, the community of Brody appointed him as one of its main dayanim. Rav Yechezkel stayed in that position for about a decade, after which he was appointed the rabbi of Yampol. After a decade, in 1755, he was chosen as the chief rabbi of one of the most important Jewish communities and cities in Europe, Prague.

In Prague, the Noda B’Yehuda continued his local rabbinic duties. His son praised him for not fleeing Prague before the Siege of Prague (1757) but staying and being of major help. His reputation drew many promising Talmudic students to study with him, the most famous of whom was Rav Avraham Danzig, author of Chayei Adam. He also was a major spokesman on both halachic matters and questions of the time, such as the attitude toward Moses Mendelson and the Haskala movement (while enjoying a broad base of knowledge that included sciences, the Noda B’yehuda was a strong opponent). In one of his most famous rulings, he opposed autopsies except those related to a specific urgent need.

In Prague, the Noda B’Yehuda continued his local rabbinic duties. His son praised him for not fleeing Prague before the Siege of Prague (1757) but staying and being of major help. His reputation drew many promising Talmudic students to study with him, the most famous of whom was Rav Avraham Danzig, author of Chayei Adam. He also was a major spokesman on both halachic matters and questions of the time, such as the attitude toward Moses Mendelson and the Haskala movement (while enjoying a broad base of knowledge that included sciences, the Noda B’yehuda was a strong opponent). In one of his most famous rulings, he opposed autopsies except those related to a specific urgent need.

Noda be-Yehudah. Manuscripts and Printed Books

Noda be-Yehudah. Manuscripts and Printed Books

One of the principal sources of Jewish law of his age.

The best known work of the great halkhic authority R' Yechezkel ben Yehuda Landau (8 October 1713 – 29 April 1793), and one of the principal sources of Jewish law of his age. Famous decisions within this collection of responsa include those limiting autopsy to prevent a clear and present danger in known others. This collection was esteemed by rabbis and scholars, both for its logic and for its independence with regard to the rulings of other Acharonim as well as its simultaneous adherence to the writings of the Rishonim.

R' Landau was born in Opatów, Poland, to a family that traced its lineage back to Rashi, and attended yeshiva at Ludmir and Brody. In Brody, he was appointed dayan (rabbinical judge) in 1734, and in 1745 he became rabbi of Yampol. While in Yampol, he attempted to mediate between R' Jacob Emden and R' Jonathan Eybeschütz. His role in this famous controversy is described as "tactful" and brought him to the attention of the community of Prague—where, in 1755, he was appointed rabbi. He also established a Yeshiva there; Avraham Danzig, author of Chayei Adam, is amongst his best known students.

R' Landau was highly esteemed by his own community and many others, and stood high in favor in government circles. In addition to his rabbinical tasks, he was able to intercede with the government on various occasions when anti-Semitic measures had been introduced. Though not opposed to secular knowledge, he objected to "that culture which came from Berlin", in particular Moses Mendelssohn's translation of the Pentateuch.

The book was printed in Sudikov. Sudilkov is a town located in the Ukraine in Kamenets-Podolski region. While it was considered a lesser brother to the great printing center of Slavuta, the Sudilkov press was strong on the reissue of classics and essential works. The town was also known for its production of Talitot (prayer shawls).

Finely designed and printed title page with architectural frame. Foliate columns flank the text; above, a ornate crowned tops a cartouche, enclosed in foliage and flanked by two lions. The same frame is used on B.1381, printed in the same year by the same printer.

The best known work of the great halkhic authority R' Yechezkel ben Yehuda Landau (8 October 1713 – 29 April 1793), and one of the principal sources of Jewish law of his age. Famous decisions within this collection of responsa include those limiting autopsy to prevent a clear and present danger in known others. This collection was esteemed by rabbis and scholars, both for its logic and for its independence with regard to the rulings of other Acharonim as well as its simultaneous adherence to the writings of the Rishonim.

R' Landau was born in Opatów, Poland, to a family that traced its lineage back to Rashi, and attended yeshiva at Ludmir and Brody. In Brody, he was appointed dayan (rabbinical judge) in 1734, and in 1745 he became rabbi of Yampol. While in Yampol, he attempted to mediate between R' Jacob Emden and R' Jonathan Eybeschütz. His role in this famous controversy is described as "tactful" and brought him to the attention of the community of Prague—where, in 1755, he was appointed rabbi. He also established a Yeshiva there; Avraham Danzig, author of Chayei Adam, is amongst his best known students.

R' Landau was highly esteemed by his own community and many others, and stood high in favor in government circles. In addition to his rabbinical tasks, he was able to intercede with the government on various occasions when anti-Semitic measures had been introduced. Though not opposed to secular knowledge, he objected to "that culture which came from Berlin", in particular Moses Mendelssohn's translation of the Pentateuch.

The book was printed in Sudikov. Sudilkov is a town located in the Ukraine in Kamenets-Podolski region. While it was considered a lesser brother to the great printing center of Slavuta, the Sudilkov press was strong on the reissue of classics and essential works. The town was also known for its production of Talitot (prayer shawls).

Finely designed and printed title page with architectural frame. Foliate columns flank the text; above, a ornate crowned tops a cartouche, enclosed in foliage and flanked by two lions. The same frame is used on B.1381, printed in the same year by the same printer.

Rav Shmuel Landau

Rav Shmuel Landau

The Noda B’yehuda’s writings are a valuable part of any serious Jewish library. It is interesting that he picked titles to commemorate his parents. His work on several Talmudic tractates is named the Tzlach, abbreviation of "A Memorial for the Spirit of Chaya." His monumental work of responsa, the Noda B’Yehuda (Known in Yehuda), is named for his father. He explained that the reason that he, Yechezkel, is known, is because he is a son of the illustrious Yehuda. He published the first volume in his lifetime. According to his son, it was a most aesthetic (in addition to brilliant) volume which he paid for with his own money and that he made no effort to profit from sales. It took 17 years after his death in 1793 for the second volume to be published. As both brothers wrote, Rav Shmuel was so busy as his father’s successor in Prague that he did not get around to editing the manuscripts his father gave him. Yaakovka and others from Brody told him firmly that the Torah world would not accept further delay. This volume includes notes and some responsa of Rav Shmuel.

Segal family since 1620

Abram Sub-Branch (Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch )

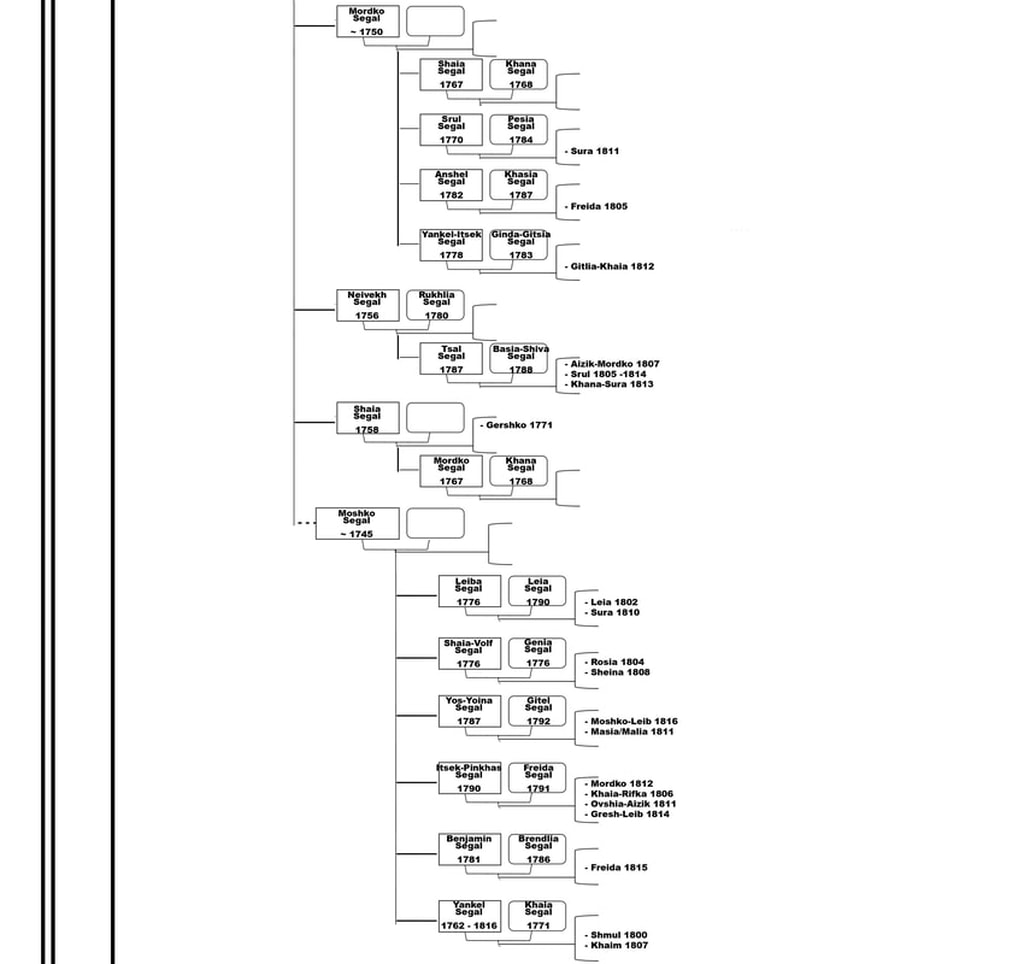

Segals from Katerinovka /(Katerburg)

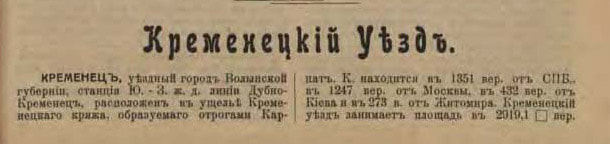

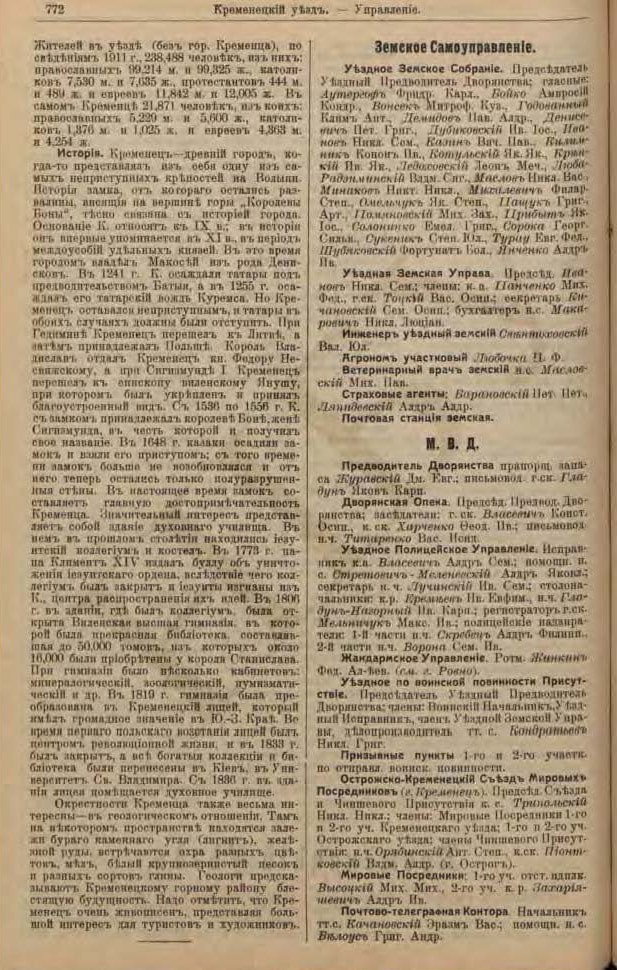

KATERYNOVKA (Ukrainian: Катеринівка, Polish: Katrynburg) until 1944 Katerburg (Russian: Катербург; Yiddish: קאַטערבורג, romanized: Katerburg) is a village and a former town in Western Ukraine. Administratively part of Kremenets Raion of the Ternopil Oblast, the village has 391 inhabitants. Katerynivka belongs to Kremenets urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine.

Initially founded in the Middle Ages as a village, the settlement was first mentioned in 1421. Throughout the ages the village bore the name of Wierzbica. The village featured a Catholic church founded by Count Plater in 1692 or 1700. In the 18th century the village's owner, Józef Plater, the castellan of Troki, turned it into a small town and renamed to Katrynburg in honour of his wife, Katarzyna Plater (née Sosnowska or Sobieska, sources differ). The name was soon shortened to Katerburg and remained in use until 1944. With time the town passed into the hands of the Ożarowski family. Between 1856 and 1877 (Mieczysław Orłowicz cites 1854-1897) Countess Cecylia Ożarowska erected a new church to replace the old one. After the January Uprising the town was confiscated from the Plater family and donated to Russian general Nikolay Bobrikov. In 1890 the church was also confiscated by the tsarist authorities and donated to a newly established Orthodox community, while the Catholic parish dissolved.

In the 19th century the town was primarily Jewish. According to 1870 data, the town had 106 houses and 815 inhabitants, 92 percent of them of Jewish ancestry. Soon after Poland regained its independence in 1918 the town of Katerburg was attached to powiat of Krzemieniec and since 1 October 1933 became a seat of a separate municipality. In 1920 the town's church was reclaimed by the Catholics. By 1929 the town had roughly 1000 inhabitants.

Following the outbreak of World War II the town was captured by the Red Army in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. In January 1940 the village of Katerburg became an administrative center of raion and in October of that year its seat was moved to a nearby town of Dederkały (modern Velyki Dederkaly). After the end of Nazi-Soviet cooperation and the outbreak of hostilities between Germany and the Soviet Union, the town was soon captured by the Wehrmacht. Roughly 400 of the town's inhabitants were rushed into a small ghetto created in the town by the Germans. The ghetto was liquidated on 10 August 1942: officers of the Sicherheitsdienst aided by military police and Ukrainian militias mass murdered 312 Polish citizens, most of them of Jewish ancestry. Several dozen people had died before that date of hunger and diseases. Another mass murder took place on 7–8 May 1943, when Ukrainian nationalists murdered 28 Poles, 10 Jews and 2 mixed Polish-Ukrainian families as part of their widespread massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. The remaining Poles fled and the town remained almost completely deserted for the remainder of World War II.

Initially founded in the Middle Ages as a village, the settlement was first mentioned in 1421. Throughout the ages the village bore the name of Wierzbica. The village featured a Catholic church founded by Count Plater in 1692 or 1700. In the 18th century the village's owner, Józef Plater, the castellan of Troki, turned it into a small town and renamed to Katrynburg in honour of his wife, Katarzyna Plater (née Sosnowska or Sobieska, sources differ). The name was soon shortened to Katerburg and remained in use until 1944. With time the town passed into the hands of the Ożarowski family. Between 1856 and 1877 (Mieczysław Orłowicz cites 1854-1897) Countess Cecylia Ożarowska erected a new church to replace the old one. After the January Uprising the town was confiscated from the Plater family and donated to Russian general Nikolay Bobrikov. In 1890 the church was also confiscated by the tsarist authorities and donated to a newly established Orthodox community, while the Catholic parish dissolved.

In the 19th century the town was primarily Jewish. According to 1870 data, the town had 106 houses and 815 inhabitants, 92 percent of them of Jewish ancestry. Soon after Poland regained its independence in 1918 the town of Katerburg was attached to powiat of Krzemieniec and since 1 October 1933 became a seat of a separate municipality. In 1920 the town's church was reclaimed by the Catholics. By 1929 the town had roughly 1000 inhabitants.

Following the outbreak of World War II the town was captured by the Red Army in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. In January 1940 the village of Katerburg became an administrative center of raion and in October of that year its seat was moved to a nearby town of Dederkały (modern Velyki Dederkaly). After the end of Nazi-Soviet cooperation and the outbreak of hostilities between Germany and the Soviet Union, the town was soon captured by the Wehrmacht. Roughly 400 of the town's inhabitants were rushed into a small ghetto created in the town by the Germans. The ghetto was liquidated on 10 August 1942: officers of the Sicherheitsdienst aided by military police and Ukrainian militias mass murdered 312 Polish citizens, most of them of Jewish ancestry. Several dozen people had died before that date of hunger and diseases. Another mass murder took place on 7–8 May 1943, when Ukrainian nationalists murdered 28 Poles, 10 Jews and 2 mixed Polish-Ukrainian families as part of their widespread massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. The remaining Poles fled and the town remained almost completely deserted for the remainder of World War II.

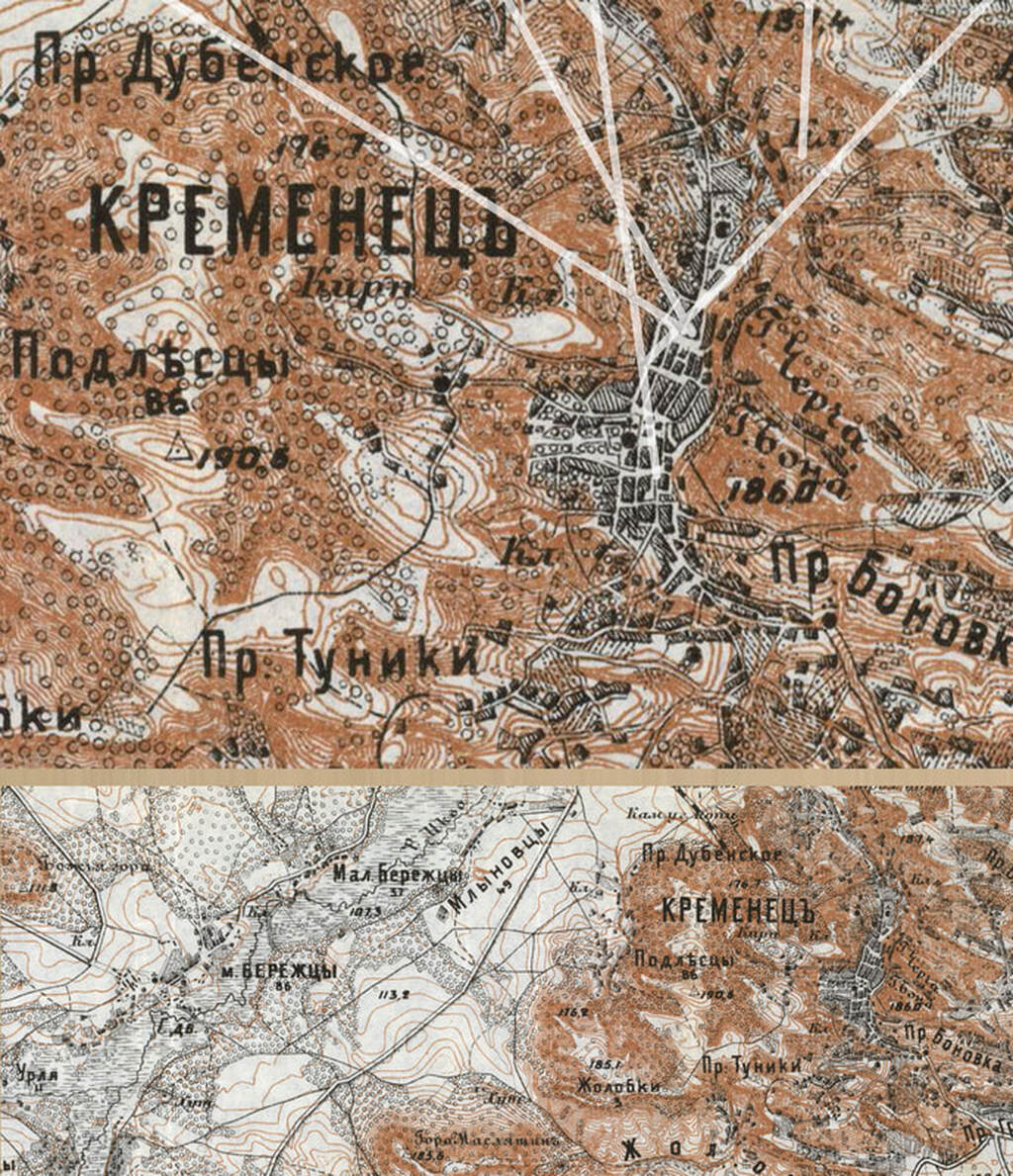

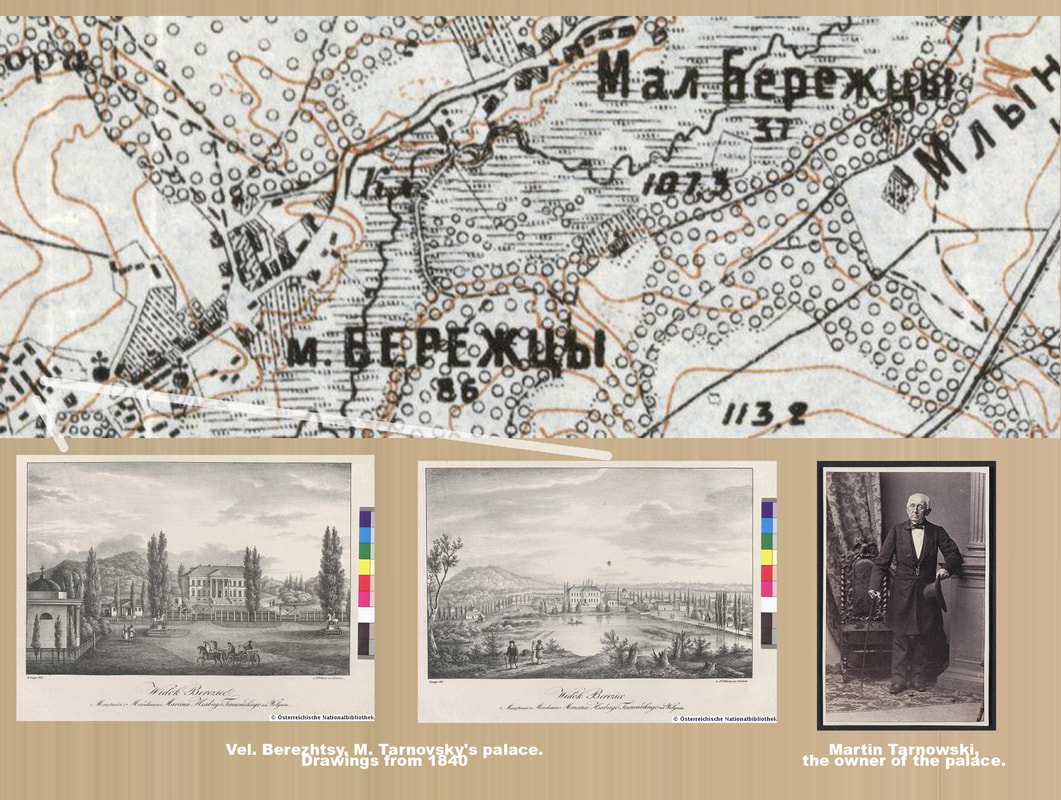

Map of Katerburg, 1913.

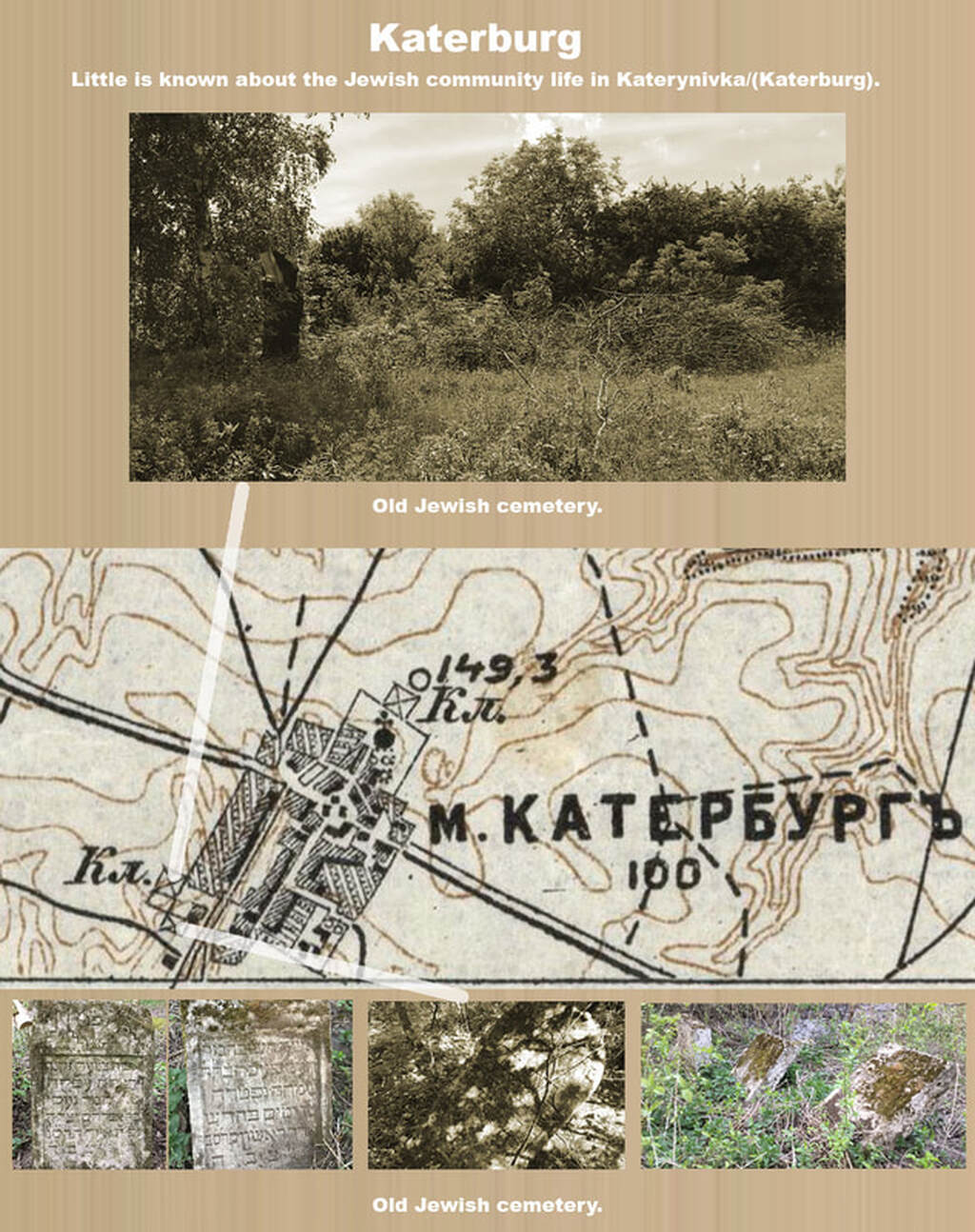

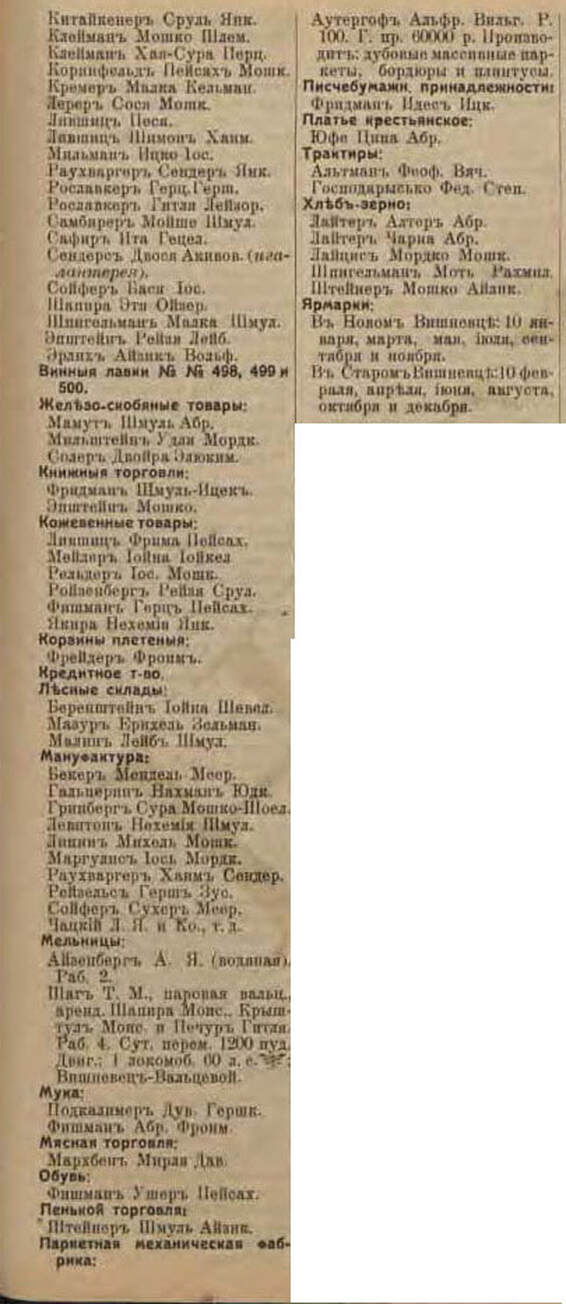

Katerburg business directory. 1913.

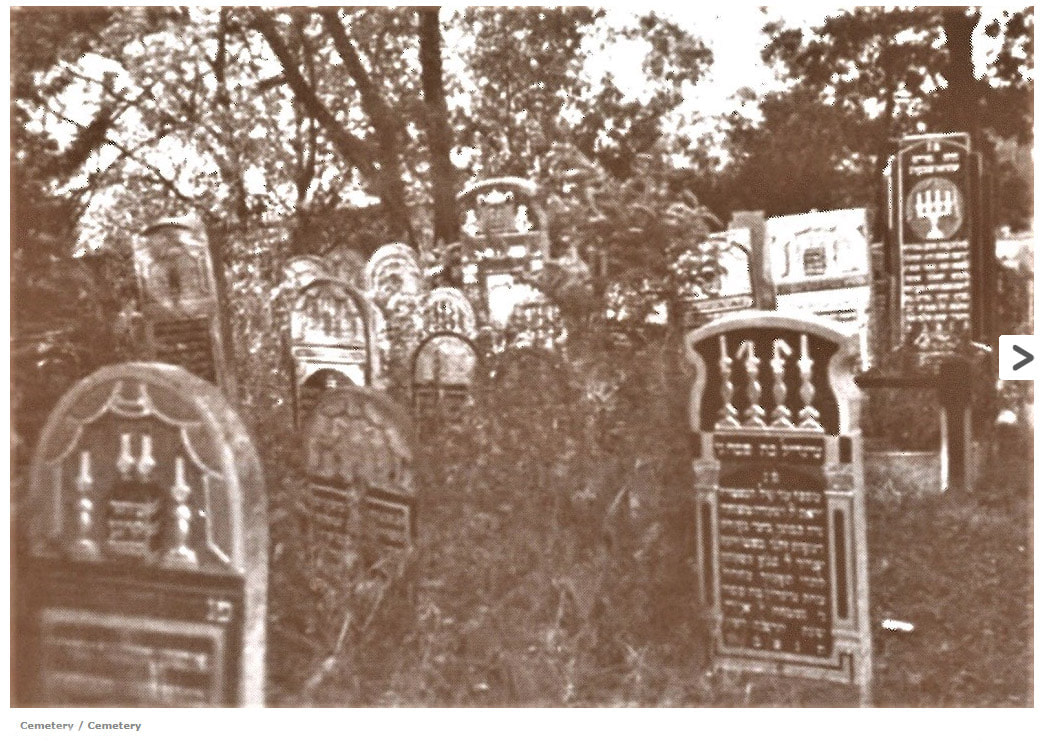

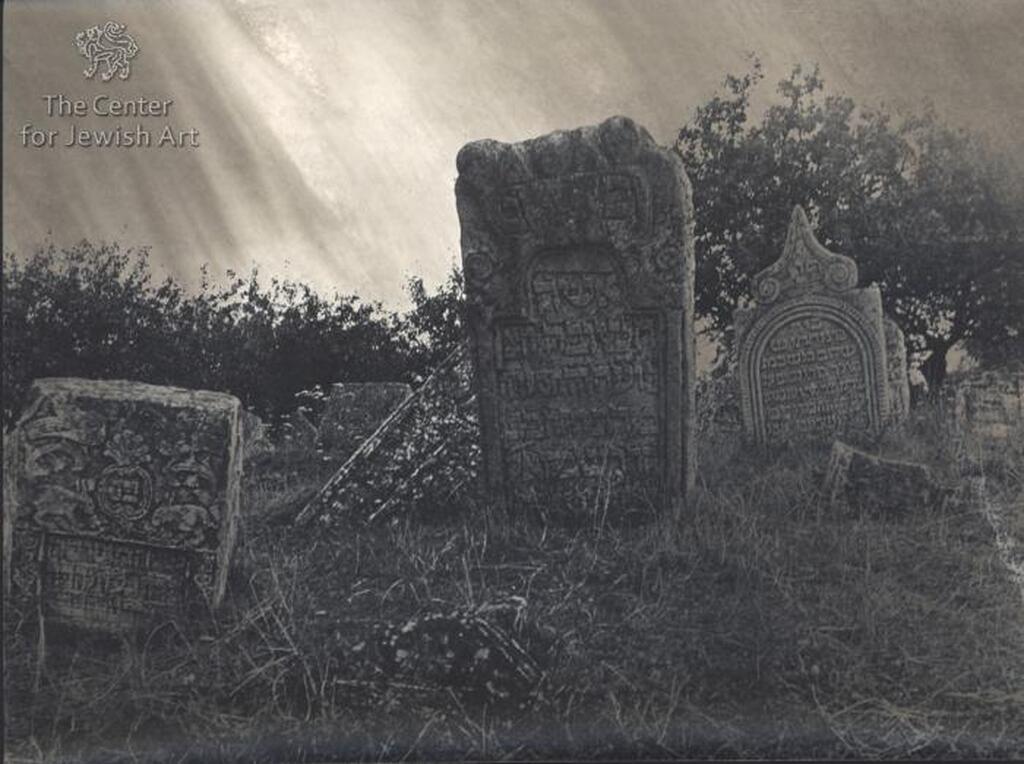

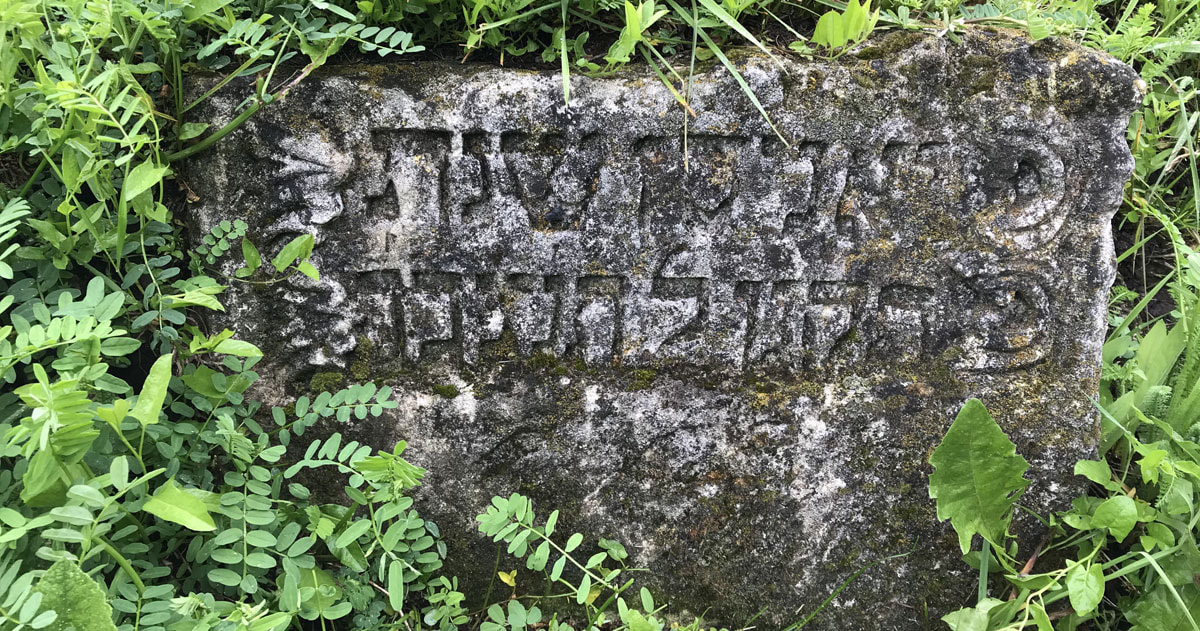

Jewish Cemetery

The earliest known Jewish community was in 17-18th century. 1939 Jewish population (census) was 384. The Jewish Community was effected by 1680 Khmelnitsky pogroms and 1919-1920 Civil War. The Jewish cemetery was established in 17-18th century with last known Hasidic (Karlin Stolin) Jewish burial in 1941. No other towns or villages used this cemetery. The isolated rural (agricultural) flat land has no sign or marker. Reached by turning directly off a public road, access is open to all. No wall, fence, or gate surrounds the site. There are 21 to 100 stones, most in original location with less than 25% of surviving common tombstones toppled or broken, dated from 17th to 20th century. No stones were removed. The site contains marked mass graves. The municipality owns the property used for Jewish cemetery. Adjacent properties are agricultural. The cemetery boundaries are unchanged since 1939. Rarely, local residents visit. The cemetery was not vandalized in the last ten years. There is no maintenance. Within the limits of the cemetery there are no structures. Vegetation overgrowth is a seasonal problem, preventing access and disturbing graves and stones. Serious threat: vegetation. Moderate threat: pollution. Slight threat: uncontrolled access, weather erosion, vandalism and proposed nearby development.

Region Ternopyl, District Kremenets', Settlement Katerynivka,

Site address

To reach the cemetery, turn to the dirt road opposite the last house on the western outskirt of the village. Proceed for 500 metres. The cemetery is located in the woods on the left of the road.

GPS coordinates 50.00397, 25.87362, Perimeter length 446 metres

Type and height of existing fence -The cemetery has a fence installed in November 2019 by ESJF.

Number of existing gravestones

About 100

Date of oldest tombstone

1876 (oldest found by ESJF expedition)

Date of newest tombstone

1920 (latest found by ESJF expedition)

Land ownership, Property of local community, Preserved construction on site

Region Ternopyl, District Kremenets', Settlement Katerynivka,

Site address

To reach the cemetery, turn to the dirt road opposite the last house on the western outskirt of the village. Proceed for 500 metres. The cemetery is located in the woods on the left of the road.

GPS coordinates 50.00397, 25.87362, Perimeter length 446 metres

Type and height of existing fence -The cemetery has a fence installed in November 2019 by ESJF.

Number of existing gravestones

About 100

Date of oldest tombstone

1876 (oldest found by ESJF expedition)

Date of newest tombstone

1920 (latest found by ESJF expedition)

Land ownership, Property of local community, Preserved construction on site

Old Jewish cemetery.

Matsevs.

Meer Sub-Sub-Branch (Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

Family of Leizer Meerovich Segal (1745)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

Family of Leizer Meerovich Segal (1745)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

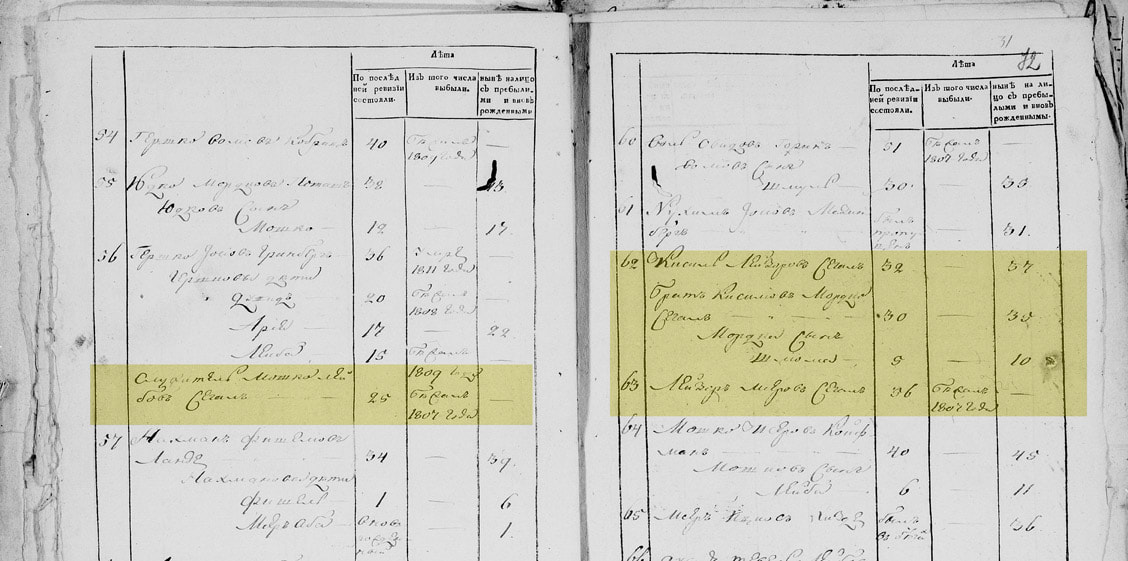

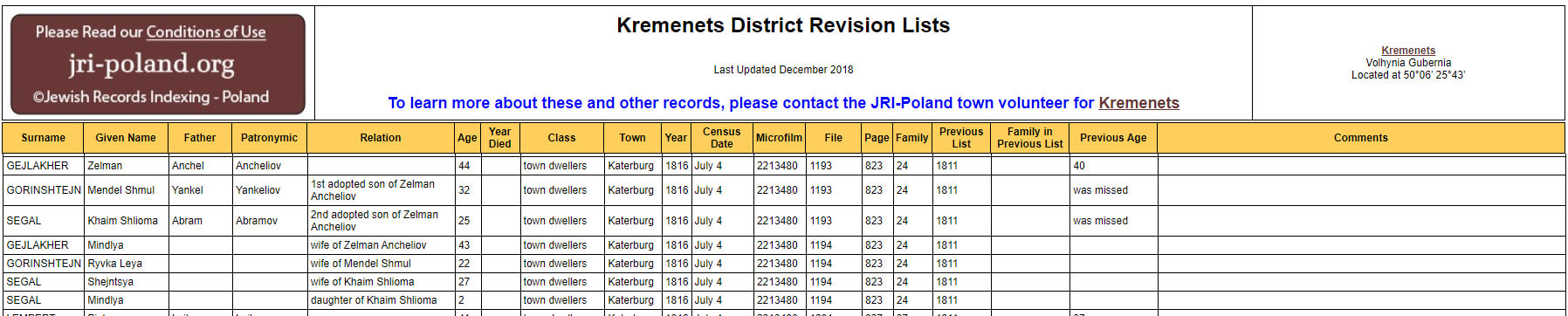

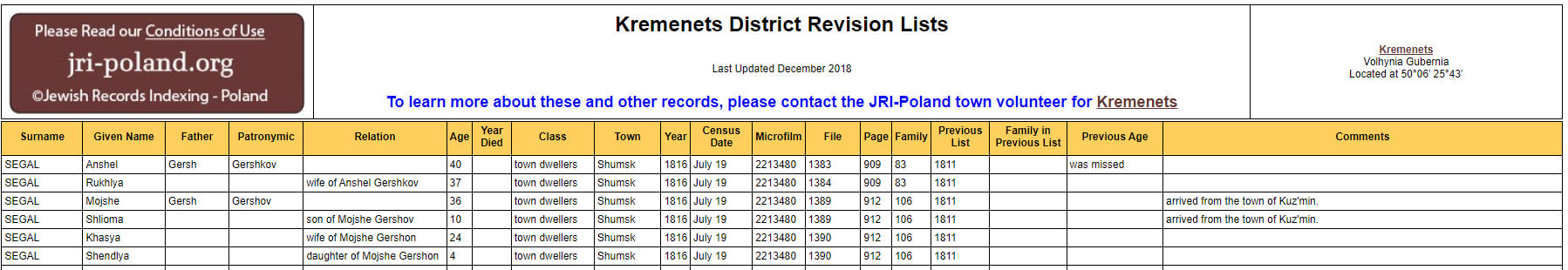

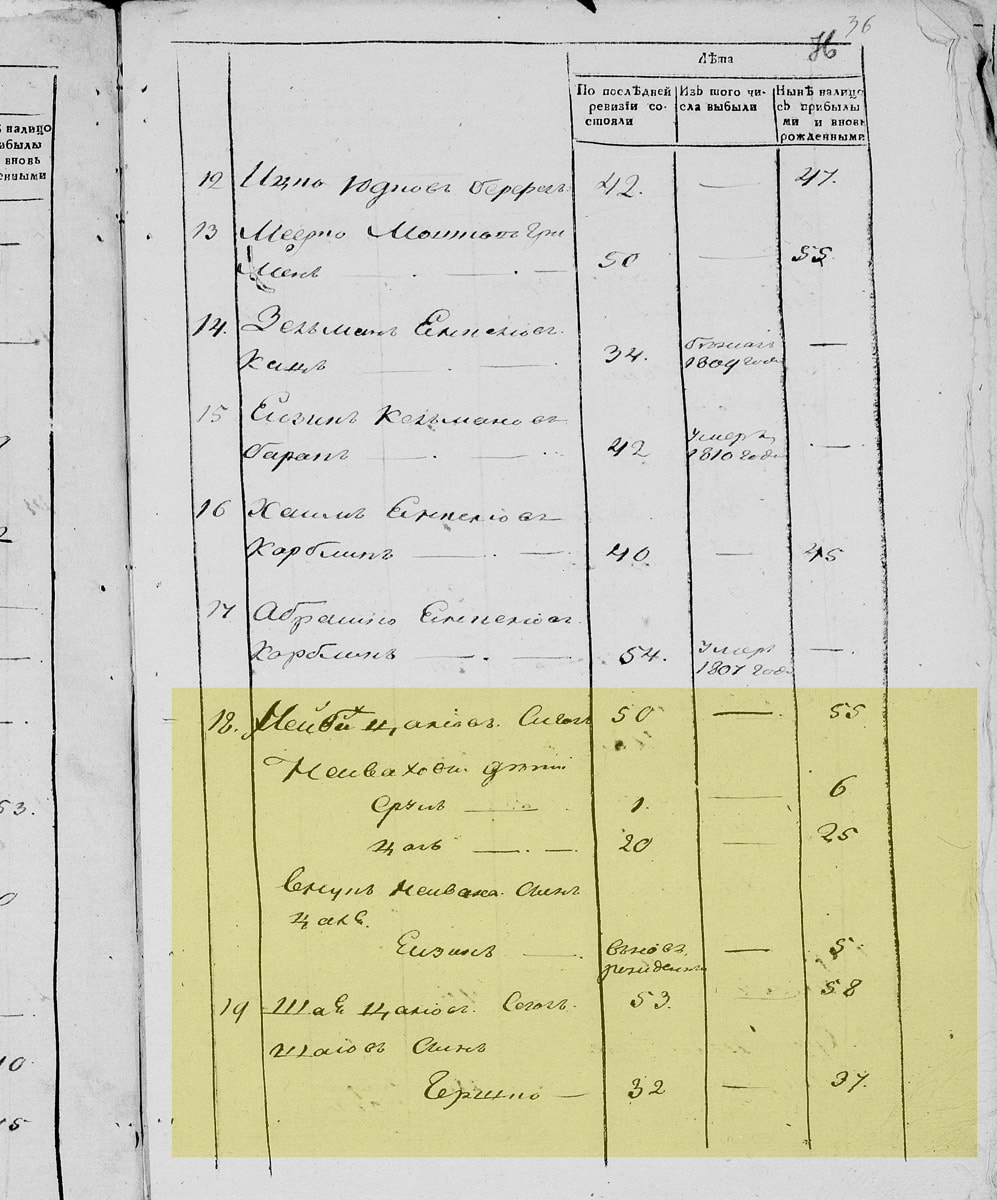

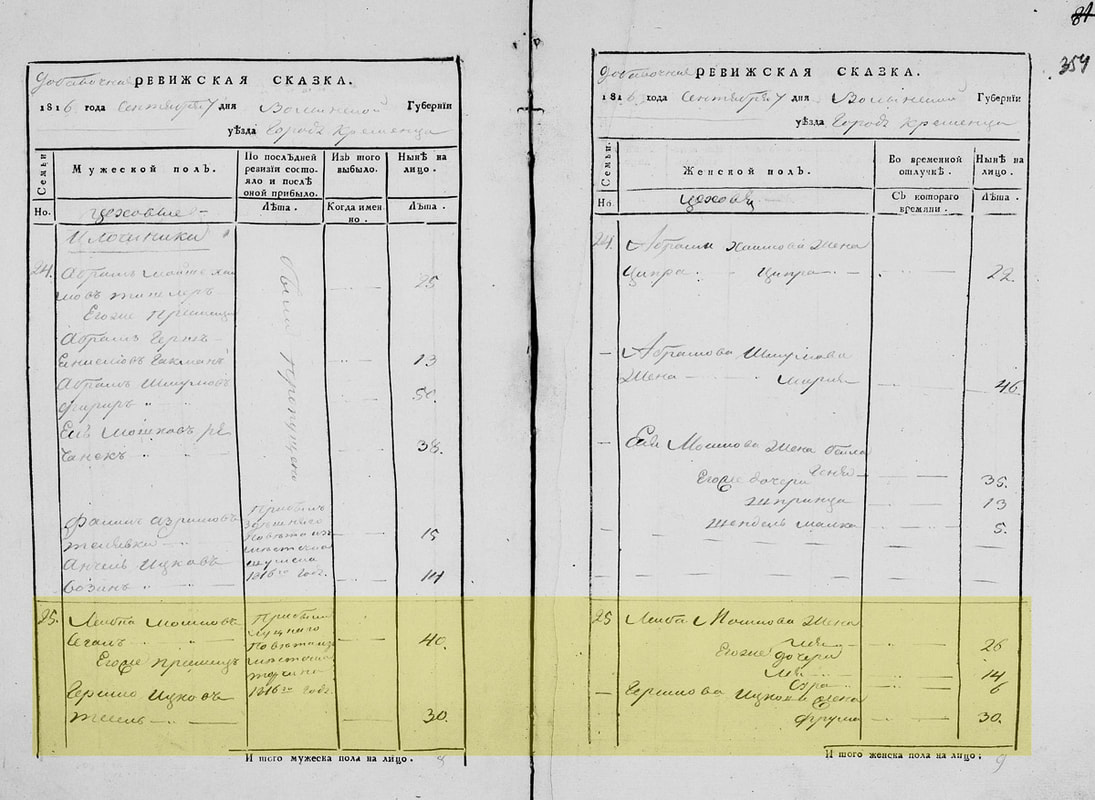

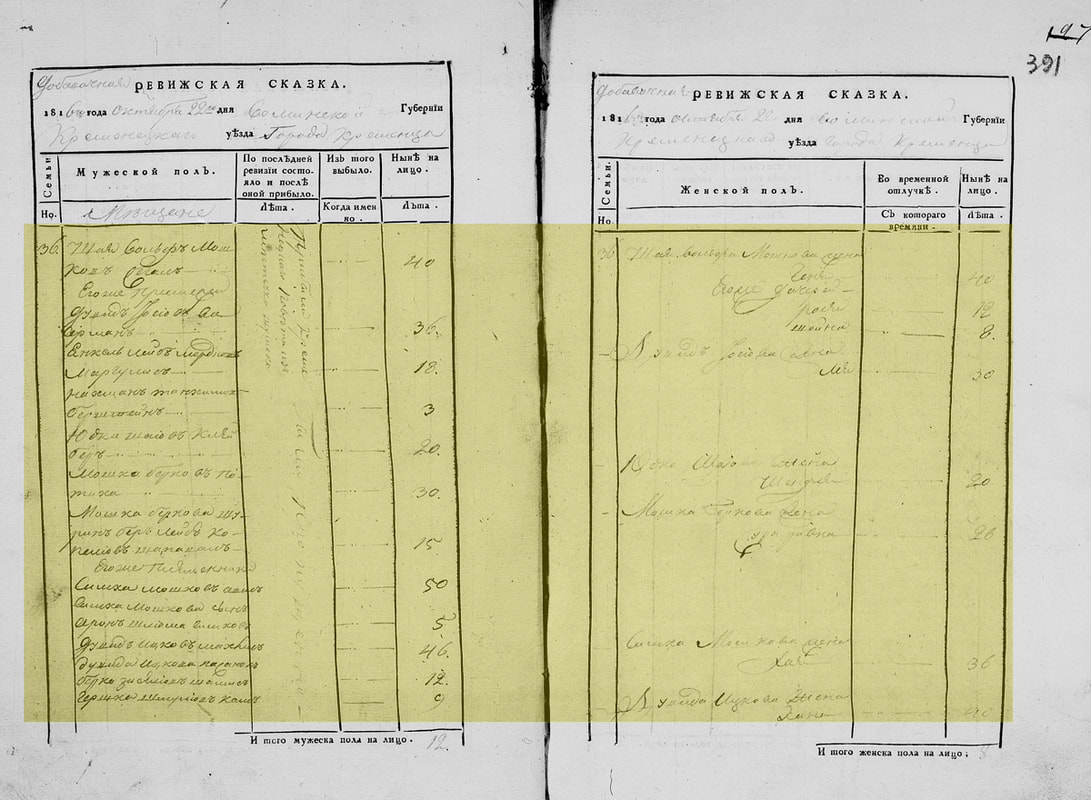

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province for 1811.

In this document of 1811, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Leizer Meerovich Segal, age 56 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1750, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 37, born in 1774, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 35, born in 1776, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

Mordko Leizerovich son - Shloma, age 10, born in 1801, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Moshko Leibovich Segal, age 25 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1781, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province for 1811.

In this document of 1811, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Leizer Meerovich Segal, age 56 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1750, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 37, born in 1774, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 35, born in 1776, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

Mordko Leizerovich son - Shloma, age 10, born in 1801, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Moshko Leibovich Segal, age 25 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1781, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

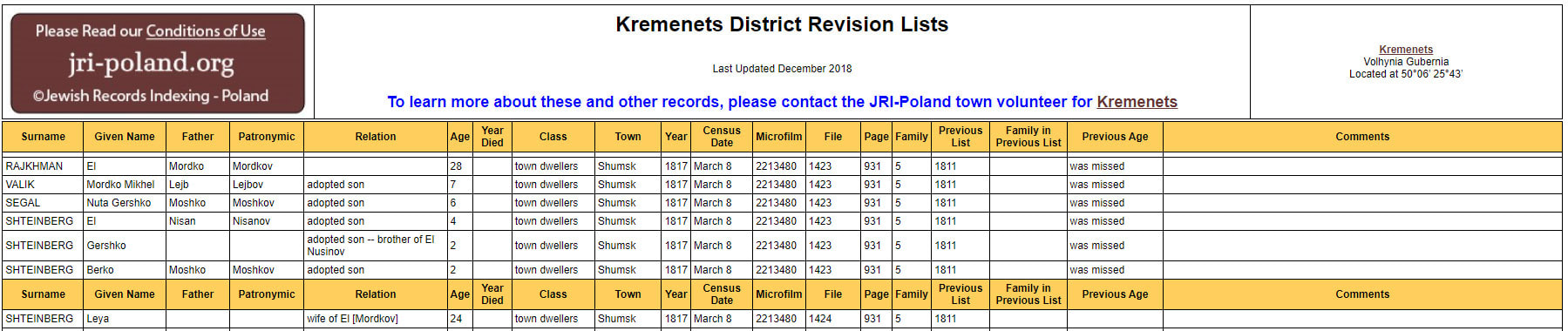

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

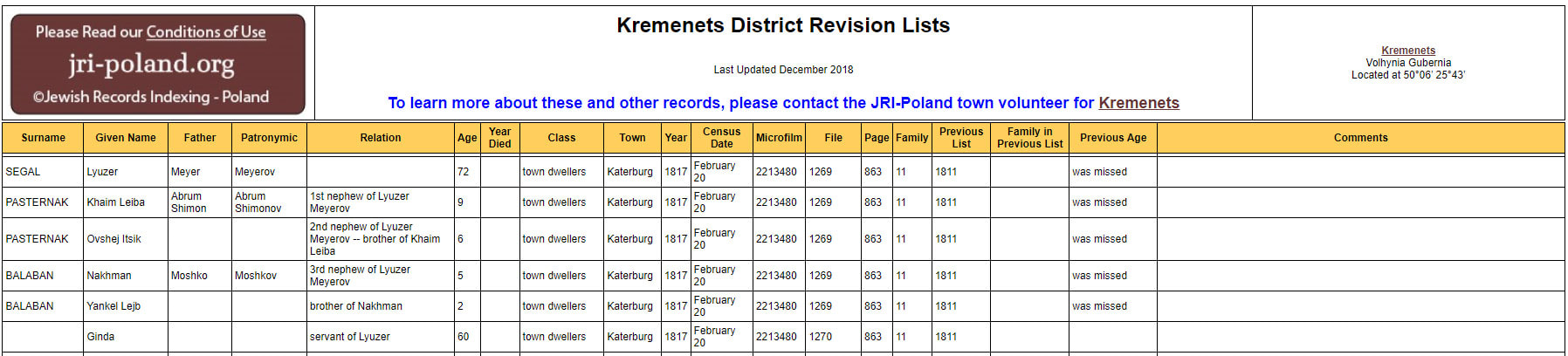

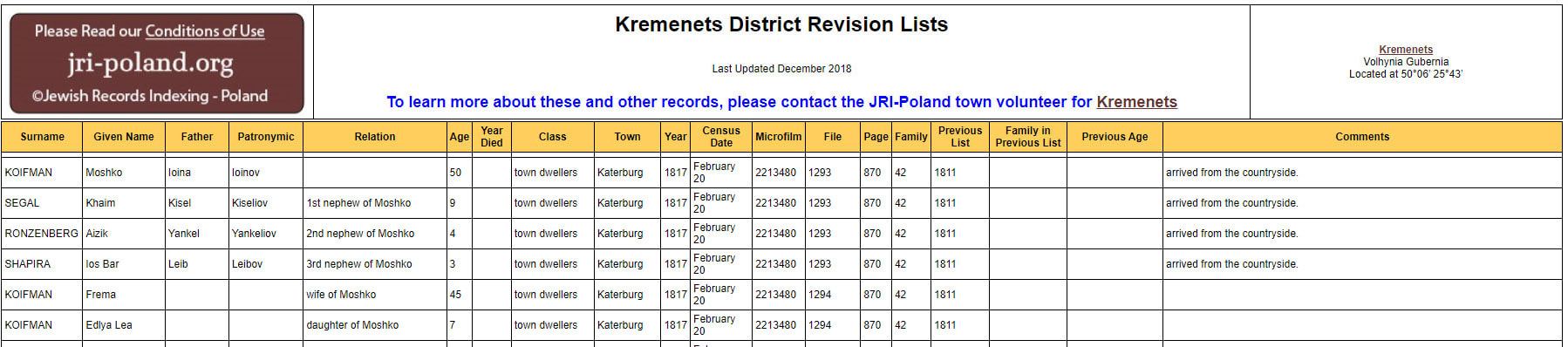

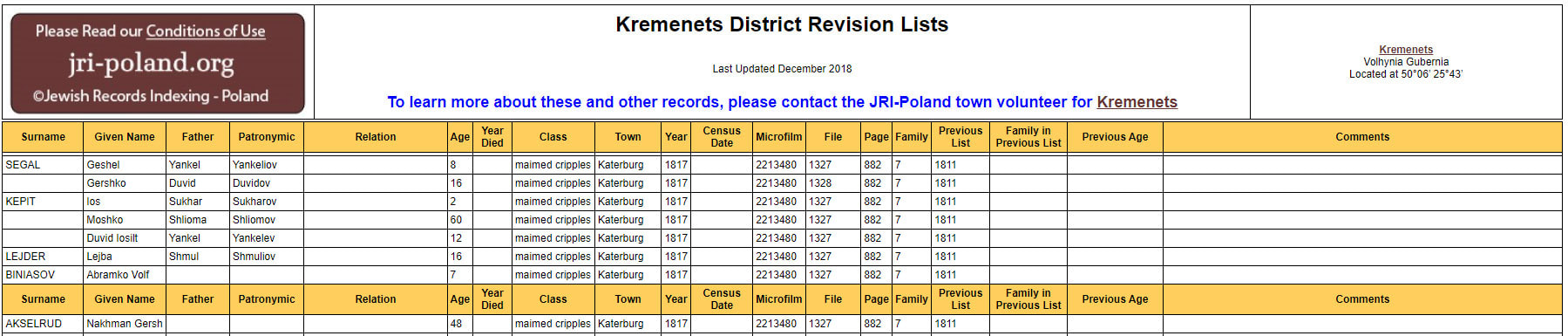

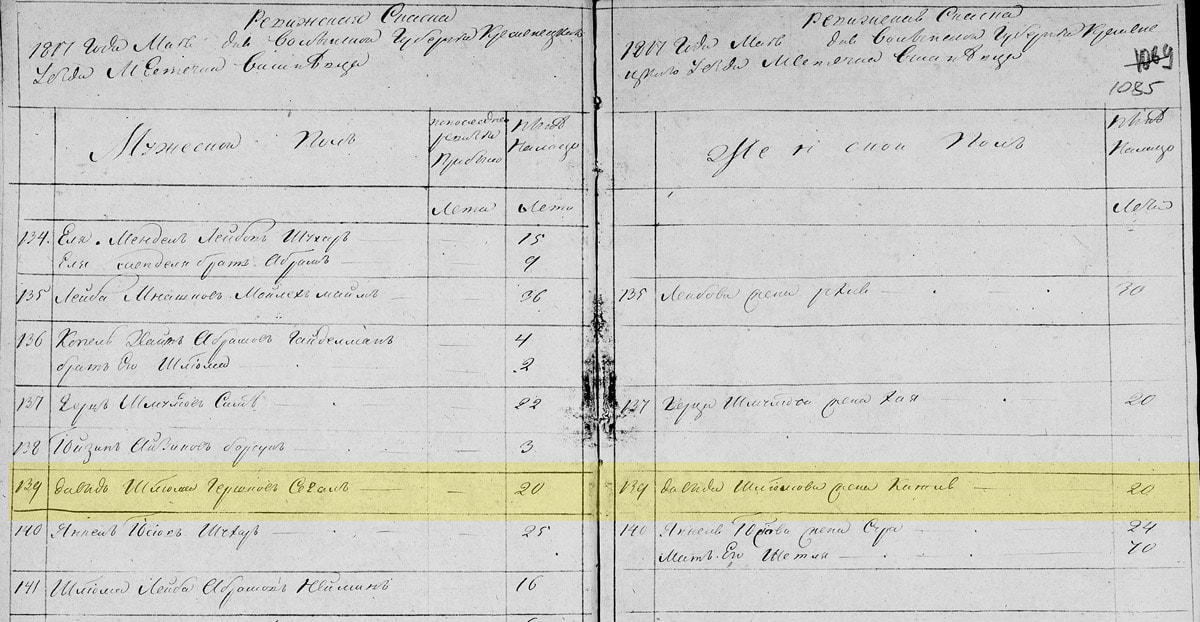

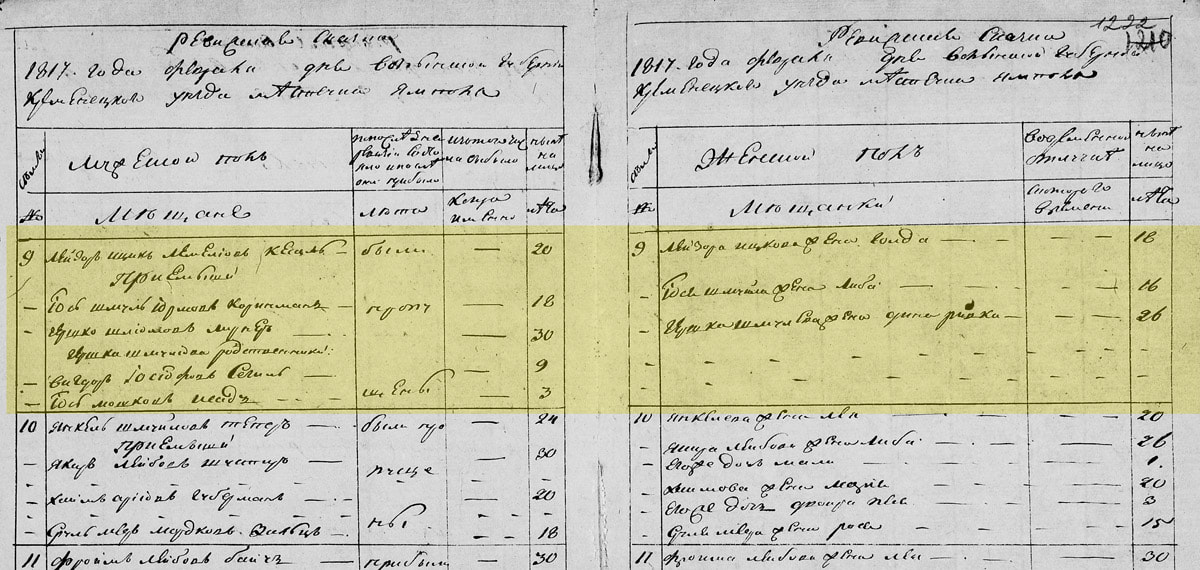

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Leizer Meerovich Segal, age 72, born in 1745, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Leizer Meerovich Segal, age 72, born in 1745, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Family of Abramko Leizerovich Segal (1769 - 1814)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

Family of Abramko Leizerovich Segal (1769 - 1814)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

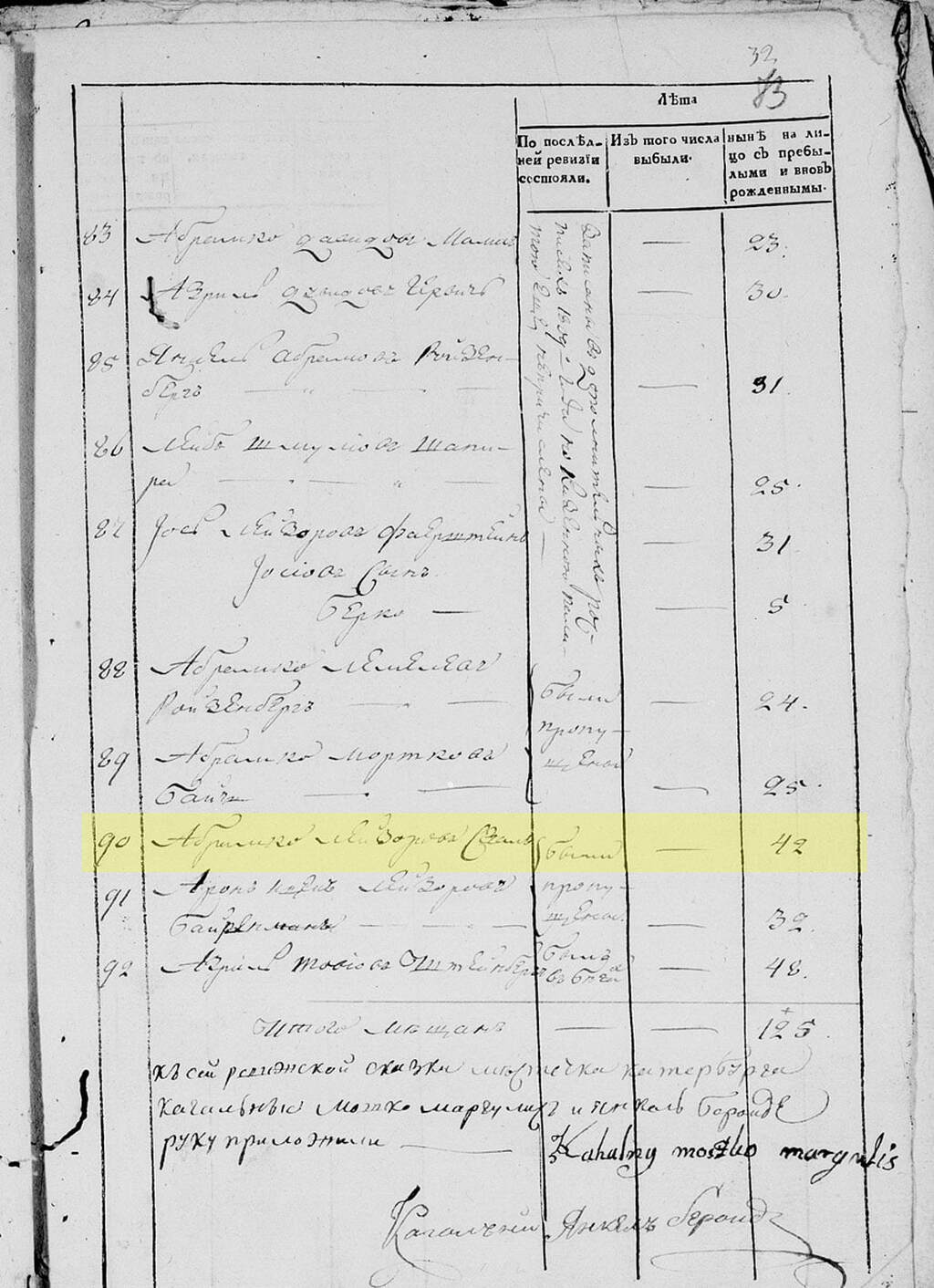

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province for 1811.

In this document of 1811, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Abramko Leizerovich Segal, age 42, born in 1769, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province for 1811.

In this document of 1811, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Abramko Leizerovich Segal, age 42, born in 1769, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

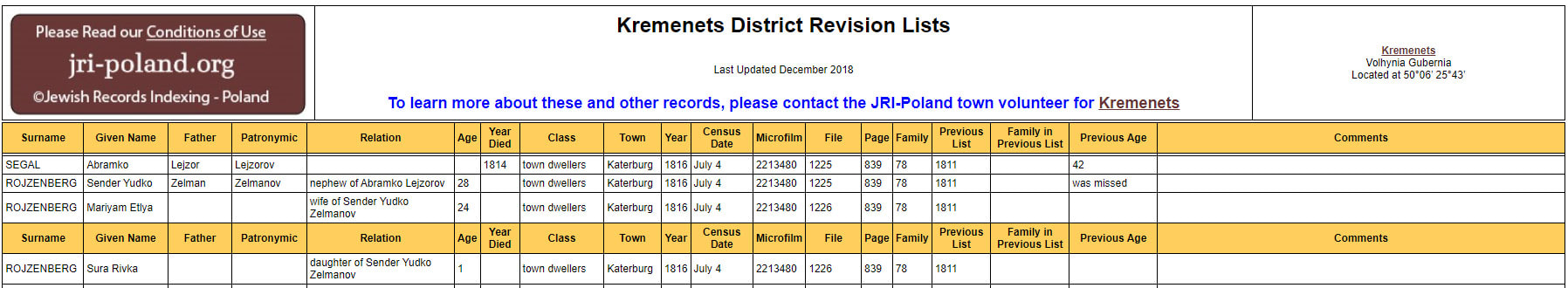

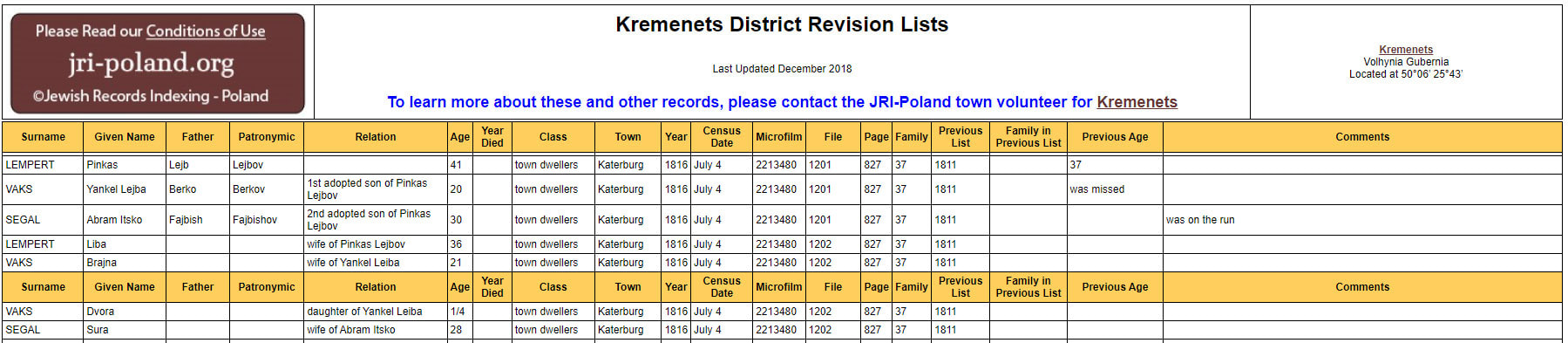

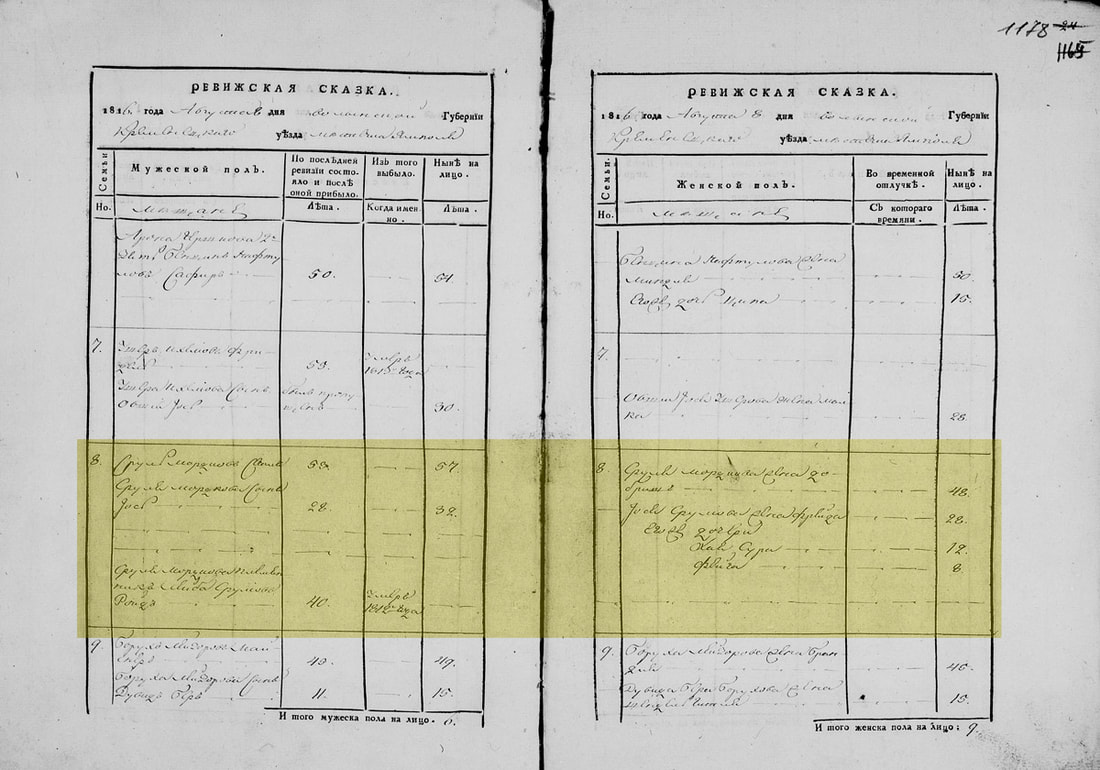

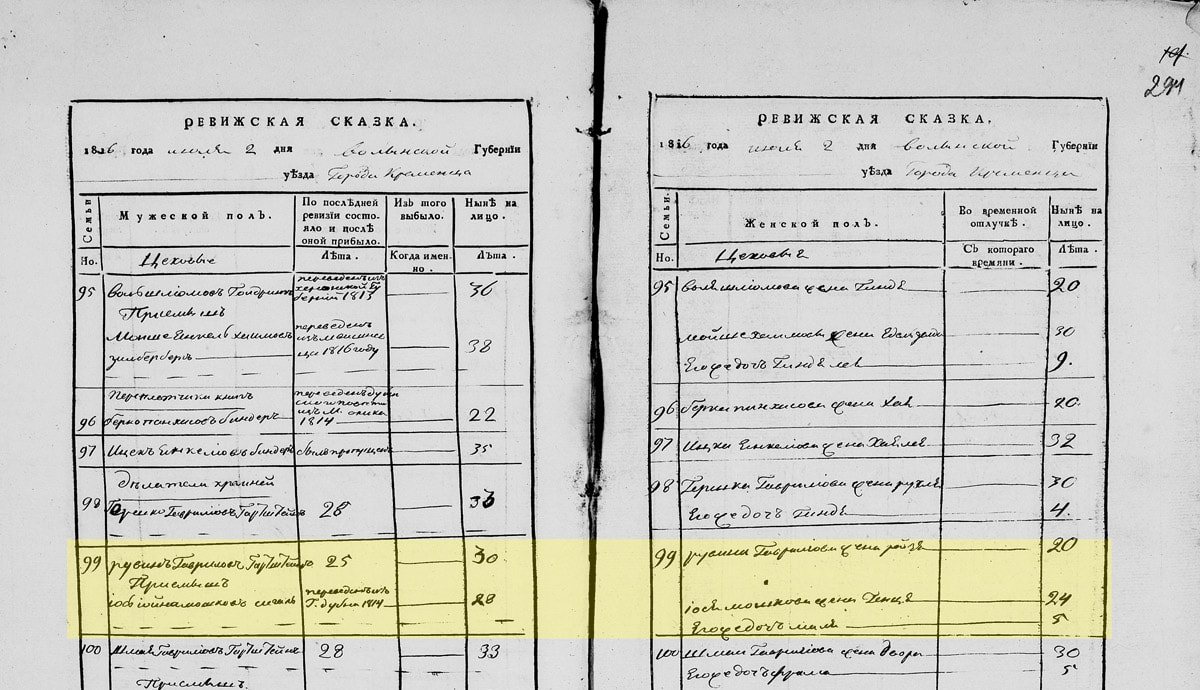

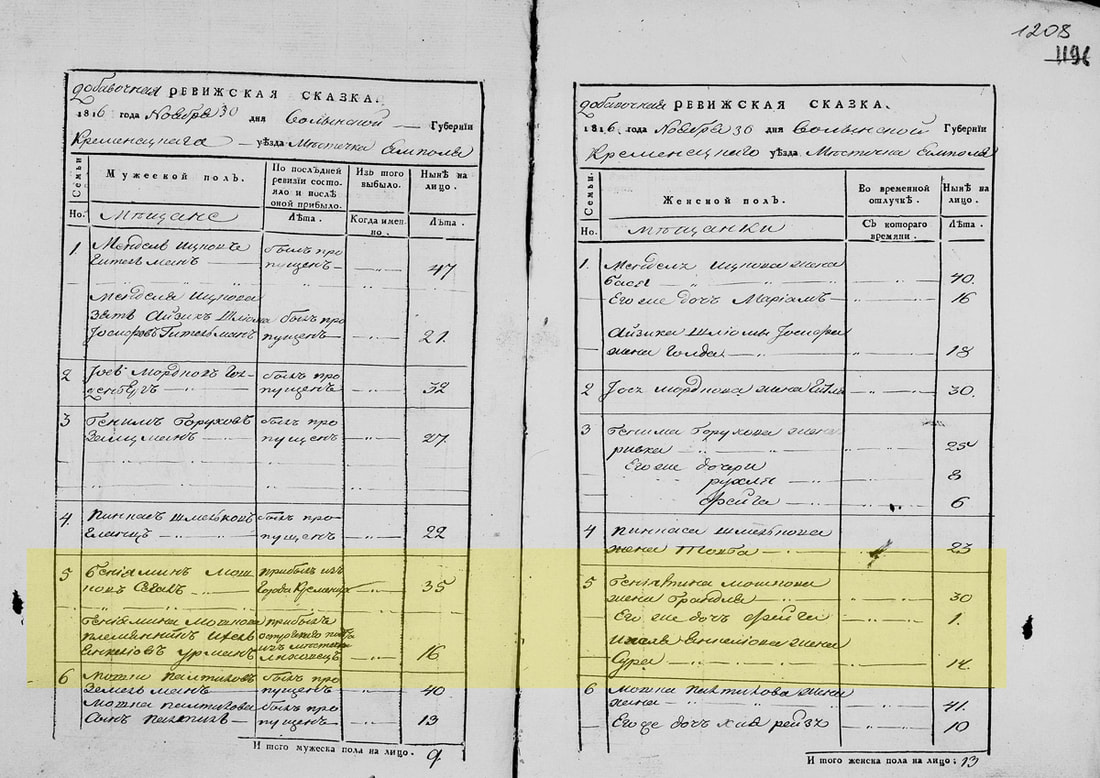

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Abramko Leizerovich Segal, age 42 in the Revision tales 1811, born in 1769, died in 1814, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Abramko Leizerovich Segal, age 42 in the Revision tales 1811, born in 1769, died in 1814, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Family of Khaim-Shloma Abramovich Segal (1791)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

Family of Khaim-Shloma Abramovich Segal (1791)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich Segal, age 25, born in 1791, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich's wife - Shejntsia, age 27, born in 1789,

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich's daughter - Mindlia, age 2, born in 1814.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich Segal, age 25, born in 1791, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich's wife - Shejntsia, age 27, born in 1789,

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich's daughter - Mindlia, age 2, born in 1814.

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

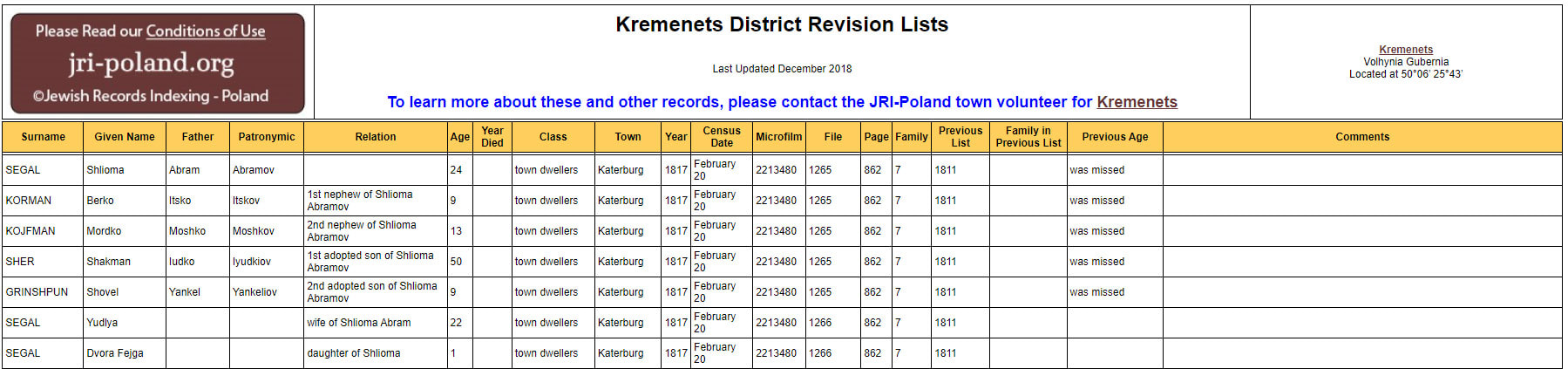

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Shloma Abramovich Segal, age 25, born in 1791, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Shloma Abramovich's wife - Yudlia, age 22, born in 1795,

- Shloma Abramovich's daughter - Dvoira-Feiga, age 1, born in 1816.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Shloma Abramovich Segal, age 25, born in 1791, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Shloma Abramovich's wife - Yudlia, age 22, born in 1795,

- Shloma Abramovich's daughter - Dvoira-Feiga, age 1, born in 1816.

Family of Anshel Abramovich Segal (1786)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

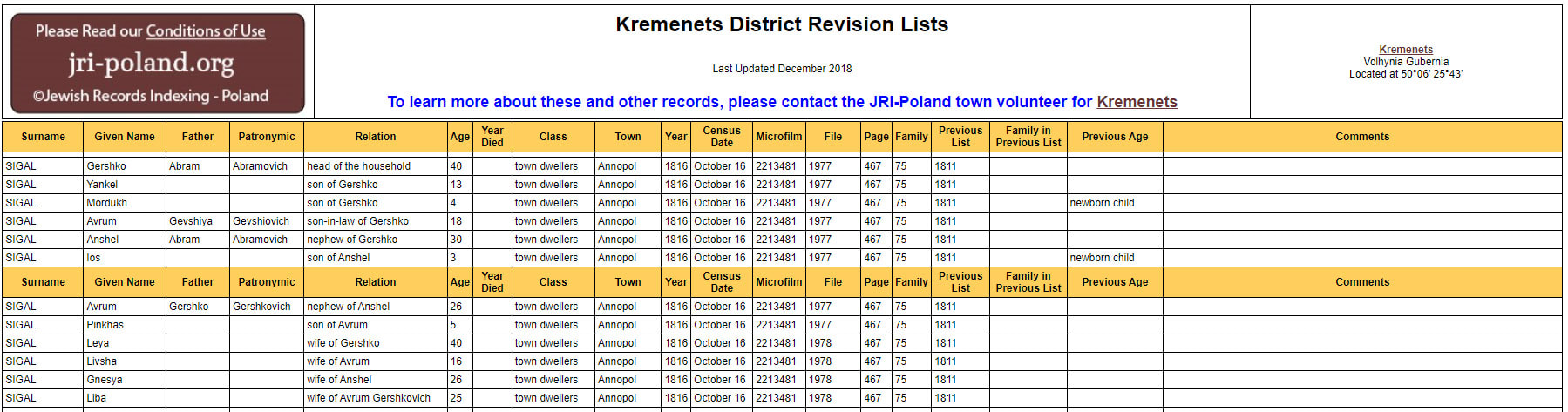

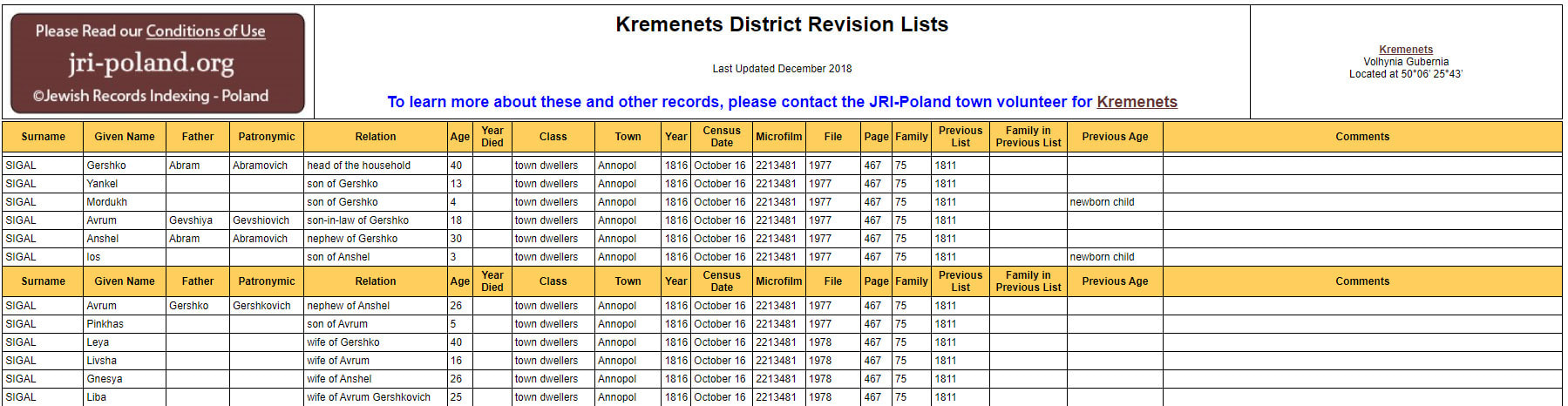

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Gershko Abramovich Segal, age 40, born in 1776, who lived in the shtetl of Annopol,

- Gershko Abramovich's son - Yankel, age 13, born in 1803,

- Gershko Abramovich's son - Mordko, age 4, born in 1812,

- Gershko Abramovich's son-in-law - Avrum Gevshiovich, age 18, born in 1798,

- Anshel Abramovich Segal, age 30, born in 1786, who lived in the shtetl of Annopol,

- Anshel Abramovich's son - Yos, age 3, born in 1813,

- Anshel Abramovich's wife - Shejntsia, age 27, born in 1789,

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich's daughter - Mindlia, age 2, born in 1814.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Gershko Abramovich Segal, age 40, born in 1776, who lived in the shtetl of Annopol,

- Gershko Abramovich's son - Yankel, age 13, born in 1803,

- Gershko Abramovich's son - Mordko, age 4, born in 1812,

- Gershko Abramovich's son-in-law - Avrum Gevshiovich, age 18, born in 1798,

- Anshel Abramovich Segal, age 30, born in 1786, who lived in the shtetl of Annopol,

- Anshel Abramovich's son - Yos, age 3, born in 1813,

- Anshel Abramovich's wife - Shejntsia, age 27, born in 1789,

- Khaim-Shloma Abramovich's daughter - Mindlia, age 2, born in 1814.

Family of Kisel Leizerovich Segal (1775)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

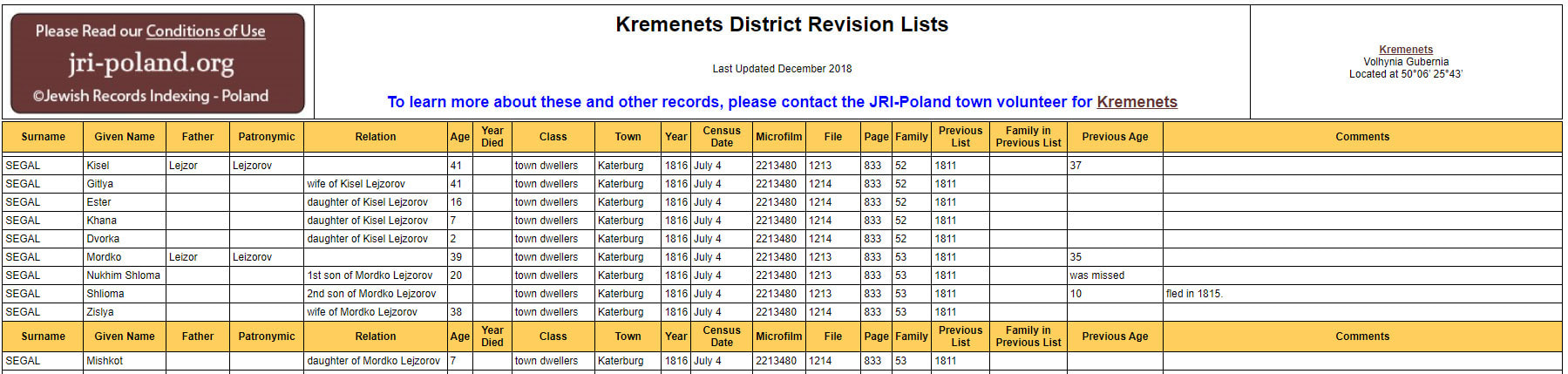

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 41, born in 1775, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Kisel Leizerovich's wife - Gitlia, age 41, born in 1775,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Ester, age 16, born in 1800,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Khana, age 8, born in 1808,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Dvoira, age 2, born in 1814,

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 39, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Nukhim-Shloma, age 20, born in 1796,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Shloma, age 10 in the Revision tales 1811, born in 1801,

- Mordko Leizerovich's wife - Zislia, age 38, born in 1778,

- Mordko Leizerovich's daughter - Mishkot, age 7, born in 1809.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 41, born in 1775, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Kisel Leizerovich's wife - Gitlia, age 41, born in 1775,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Ester, age 16, born in 1800,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Khana, age 8, born in 1808,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Dvoira, age 2, born in 1814,

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 39, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Nukhim-Shloma, age 20, born in 1796,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Shloma, age 10 in the Revision tales 1811, born in 1801,

- Mordko Leizerovich's wife - Zislia, age 38, born in 1778,

- Mordko Leizerovich's daughter - Mishkot, age 7, born in 1809.

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

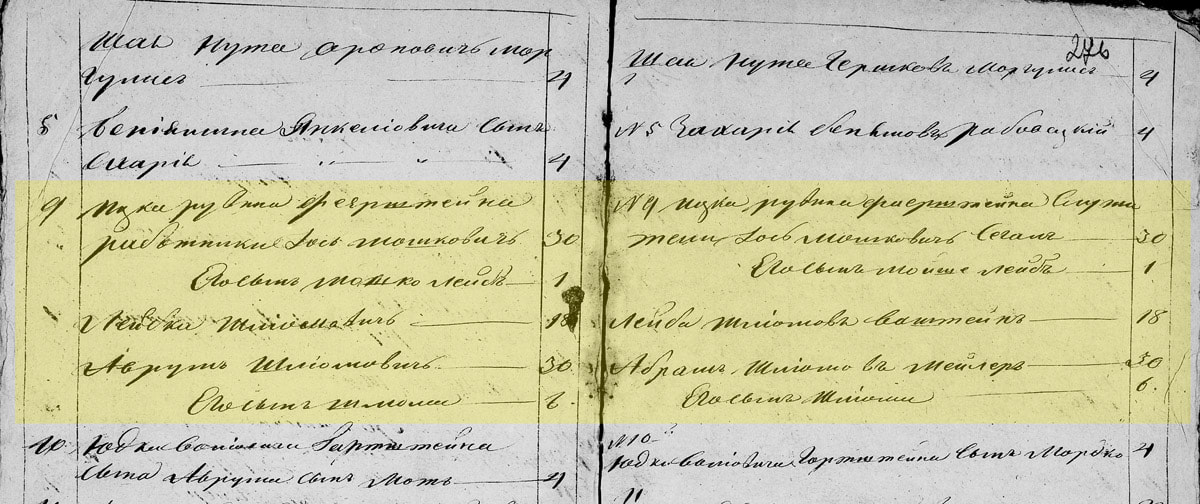

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim Kiselevich Segal, age 9, born in 1808, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim Kiselevich Segal, age 9, born in 1808, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

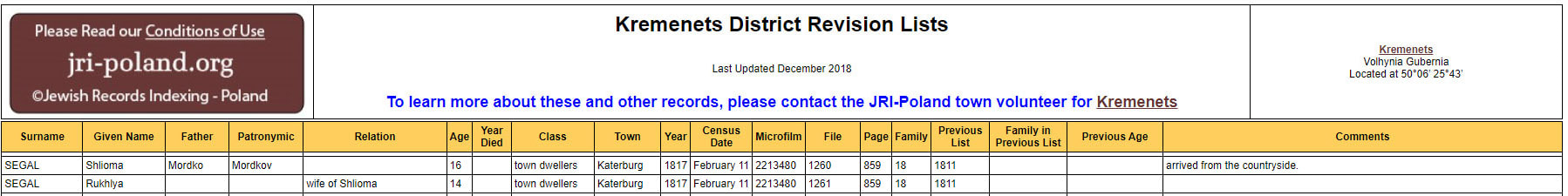

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Shloma Mordkovich Segal, age 16, born in 1801, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Shloma Mordkovich's wife - Rukhlia, age 14, born in 1803.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Shloma Mordkovich Segal, age 16, born in 1801, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Shloma Mordkovich's wife - Rukhlia, age 14, born in 1803.

Family of Mordko Leizerovich Segal (1777)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 41, born in 1775, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Kisel Leizerovich's wife - Gitlia, age 41, born in 1775,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Ester, age 16, born in 1800,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Khana, age 8, born in 1808,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Dvoira, age 2, born in 1814,

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 39, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Nukhim-Shloma, age 20, born in 1796,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Shloma, age 10 in the Revision tales 1811, born in 1801,

- Mordko Leizerovich's wife - Zislia, age 38, born in 1778,

- Mordko Leizerovich's daughter - Mishkot, age 7, born in 1809.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 41, born in 1775, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Kisel Leizerovich's wife - Gitlia, age 41, born in 1775,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Ester, age 16, born in 1800,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Khana, age 8, born in 1808,

- Kisel Leizerovich's daughter - Dvoira, age 2, born in 1814,

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 39, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Nukhim-Shloma, age 20, born in 1796,

- Mordko Leizerovich's son - Shloma, age 10 in the Revision tales 1811, born in 1801,

- Mordko Leizerovich's wife - Zislia, age 38, born in 1778,

- Mordko Leizerovich's daughter - Mishkot, age 7, born in 1809.

Family of Khaim Leizerovich Segal (1787)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

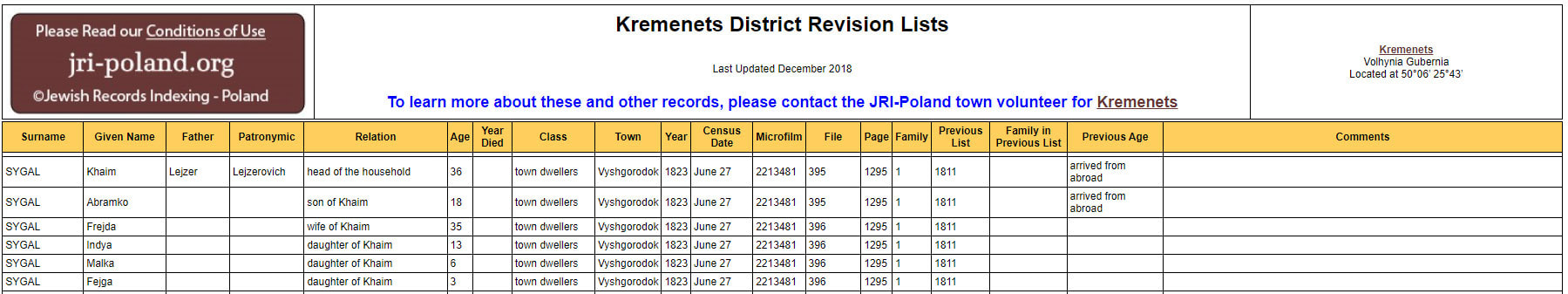

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1823

In this document of 1823, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim Leizerovich Segal, age 36, born in 1787, who lived in the shtetl of Vyshgorodok,

- Khaim Leizerovich's son - Abramko, age 18, born in 1805,

- Khaim Leizerovich's wife - Freida, age 35, born in 1788,

- Khaim Leizerovich's daughter - India, age 13, born in 1810,

- Khaim Leizerovich's daughter - Malka, age 6, born in 1817,

- Khaim Leizerovich's daughter - Feiga, age 3, born in 1820.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1823

In this document of 1823, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim Leizerovich Segal, age 36, born in 1787, who lived in the shtetl of Vyshgorodok,

- Khaim Leizerovich's son - Abramko, age 18, born in 1805,

- Khaim Leizerovich's wife - Freida, age 35, born in 1788,

- Khaim Leizerovich's daughter - India, age 13, born in 1810,

- Khaim Leizerovich's daughter - Malka, age 6, born in 1817,

- Khaim Leizerovich's daughter - Feiga, age 3, born in 1820.

Family of Yos Meerovich Segal (1783)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

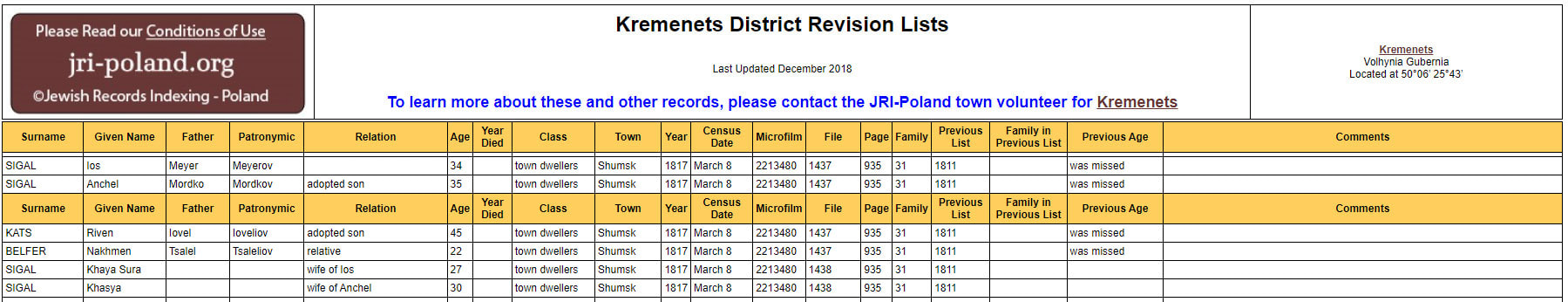

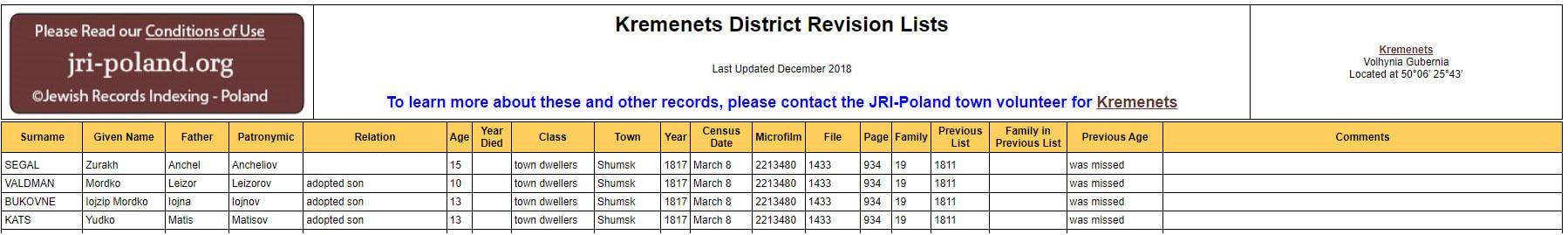

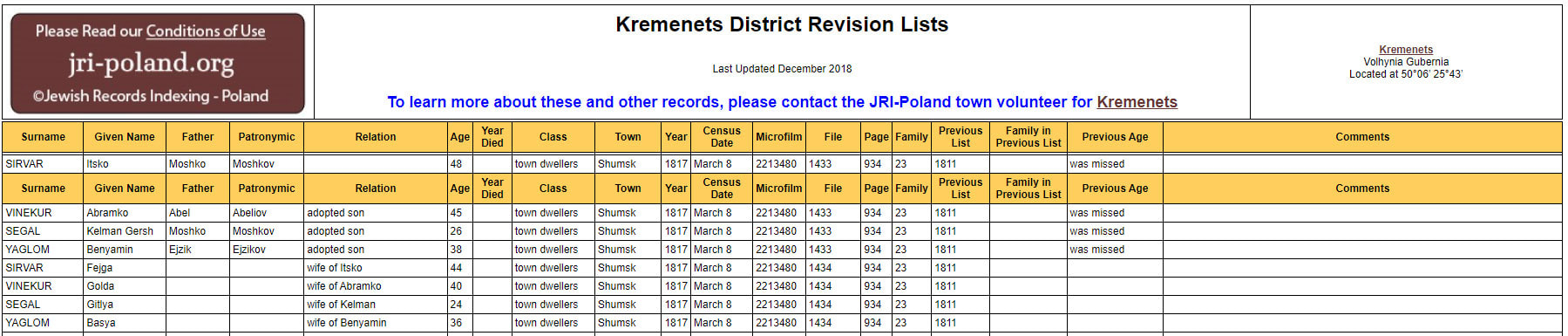

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Yos Meerovich Segal, age 34, born in 1783, who lived in the shtetl of Shumsk,

- Yos Meerovich's wife - Khaia-Sura, age 27, born in 1790.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Yos Meerovich Segal, age 34, born in 1783, who lived in the shtetl of Shumsk,

- Yos Meerovich's wife - Khaia-Sura, age 27, born in 1790.

Family of Mordko Meerovich Segal (1796)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Mordko Meerovich Segal, age 20, born in 1796, who lived in the shtetl of Pochaev,

- Mordko Meerovich's wife - Rifka, age 20, born in 1796,

- Mordko Meerovich's daughter - Leia-Basia, age 3, born in 1813.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Mordko Meerovich Segal, age 20, born in 1796, who lived in the shtetl of Pochaev,

- Mordko Meerovich's wife - Rifka, age 20, born in 1796,

- Mordko Meerovich's daughter - Leia-Basia, age 3, born in 1813.

Family of Meer-Gersh Leibovich Segal (1777)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

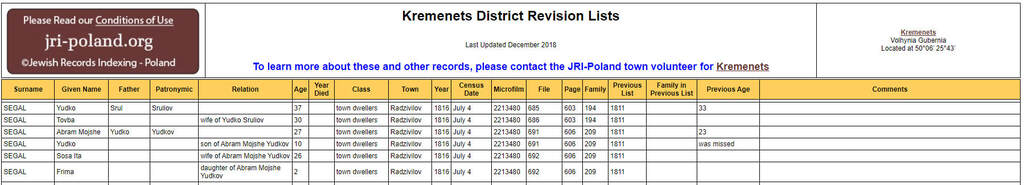

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Meer-Gersh Leibovich Segal, age 39, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Radzivilov,

- Meer-Gersh Leibovich's wife - Dishlia, age 40, born in 1776,

- Meer-Gersh Leibovich's son - Itsek, age 25, born in 1791,

- Itsek Gershkovich's wife - Toiba, age 25, born in 1791,

- Itsek Gershkovich's daughter - Freida-Leia, age 3, born in 1813.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Meer-Gersh Leibovich Segal, age 39, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Radzivilov,

- Meer-Gersh Leibovich's wife - Dishlia, age 40, born in 1776,

- Meer-Gersh Leibovich's son - Itsek, age 25, born in 1791,

- Itsek Gershkovich's wife - Toiba, age 25, born in 1791,

- Itsek Gershkovich's daughter - Freida-Leia, age 3, born in 1813.

Family of Moshko Leibovich Segal (1781)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province for 1811.

In this document of 1811, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Leizer Meerovich Segal, age 56 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1750, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 37, born in 1774, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 35, born in 1776, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

Mordko Leizerovich son - Shloma, age 10, born in 1801, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Moshko Leibovich Segal, age 25 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1781, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province for 1811.

In this document of 1811, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Leizer Meerovich Segal, age 56 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1750, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Kisel Leizerovich Segal, age 37, born in 1774, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Mordko Leizerovich Segal, age 35, born in 1776, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

Mordko Leizerovich son - Shloma, age 10, born in 1801, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg),

- Moshko Leibovich Segal, age 25 in the Revision tales 1806, born in 1781, who lived in the shtetl of Katerinovka /(Katerburg).

Ovshia Sub-Sub-Branch (Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch )

Family of Itsko-Zavel Ovshievicha Segal (1777)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Itsko-Zavel Ovshievich Segal, age 35, born in 1781, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Itsko-Zavel Ovshievich's wife - Malka, age 33, born in 1783,

- Itsko-Zavel Ovshievich's daughter - Freida, age 16, born in 1800,

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Itsko Ovshievich Segal, age 40, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Itsko Ovshievich's wife - Mindlia, age 24, born in 1793,

- Itsko Ovshievich's son - Yankel-Udko, age 16, born in 1801,

- Itsko Ovshievich's son - Khaim, age 14, born in 1803,

- Itsko Ovshievich's son - Faibish, age 2, born in 1815,

- Itsko Ovshievich's daughter - Mariam, age 12, born in 1805.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Itsko-Zavel Ovshievich Segal, age 35, born in 1781, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Itsko-Zavel Ovshievich's wife - Malka, age 33, born in 1783,

- Itsko-Zavel Ovshievich's daughter - Freida, age 16, born in 1800,

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Itsko Ovshievich Segal, age 40, born in 1777, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Itsko Ovshievich's wife - Mindlia, age 24, born in 1793,

- Itsko Ovshievich's son - Yankel-Udko, age 16, born in 1801,

- Itsko Ovshievich's son - Khaim, age 14, born in 1803,

- Itsko Ovshievich's son - Faibish, age 2, born in 1815,

- Itsko Ovshievich's daughter - Mariam, age 12, born in 1805.

Family of Khaim Yankelevich Segal (1815)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim Yankelevich Segal, age 2, born in 1815, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Khaim Yankelevich Segal, age 2, born in 1815, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg.

Family of Gershel Yankelevich Segal (1809)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Gershel Yankelevich Segal, age 8, born in 1809, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Gershel Yankelevich Segal, age 8, born in 1809, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg.

Family of Abram-Itsko Fibishevich Segal (1786)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich Segal, age 30, born in 1786, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's wife - Sura, age 28, born in 1788,

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich Segal, age 30, born in 1786, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's wife - Sura, age 28, born in 1788,

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

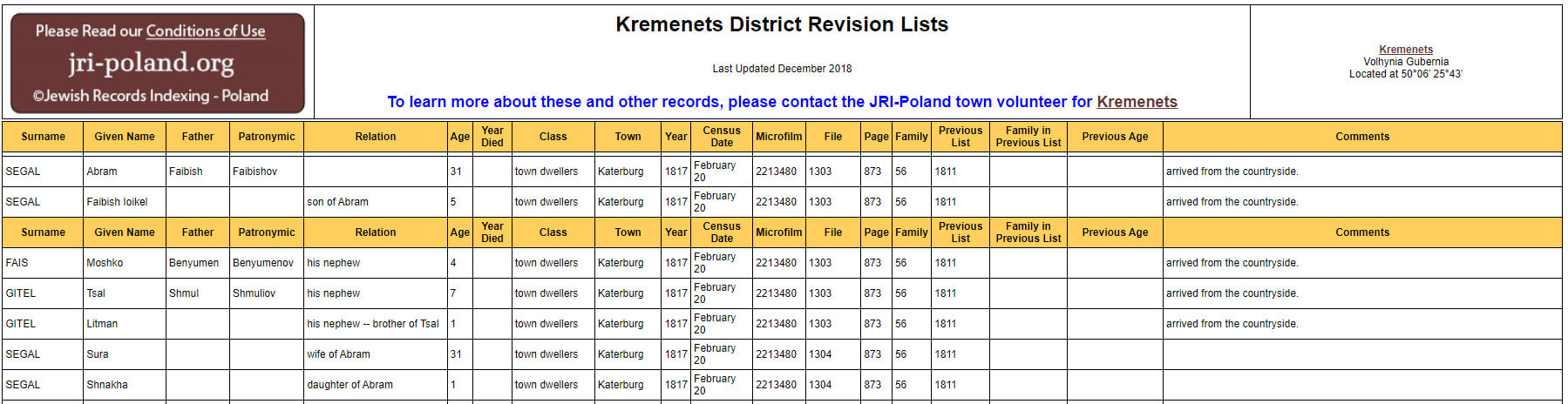

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich Segal, age 31, born in 1786, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's wife - Sura, age 31, born in 1786,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's son - Faibish-Yoikel, age 5, born in 1812,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's daughter - Shnakha, age 1, born in 1816.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1817.

In this document of 1817, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich Segal, age 31, born in 1786, who lived in the shtetl of Katerburg,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's wife - Sura, age 31, born in 1786,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's son - Faibish-Yoikel, age 5, born in 1812,

- Avrum-Itsko Faibishovich's daughter - Shnakha, age 1, born in 1816.

Family of Avrum Ovshievicha Segal (1798)( Sagalov tree, descendants of Itsko-Ayzik, Khaim Branch)

State Archive of the Ternopil region.

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Avrum Ovshievich Segal, age 18, born in 1798, who lived in the shtetl of Annopol,

- Avrum Ovshievich's wife - Livsha, age 16, born in 1800,

Revision tales about the Jews of the Volyn province. 1816

In this document of 1816, among the male Jews appears the family's of our relatives:

- Avrum Ovshievich Segal, age 18, born in 1798, who lived in the shtetl of Annopol,

- Avrum Ovshievich's wife - Livsha, age 16, born in 1800,

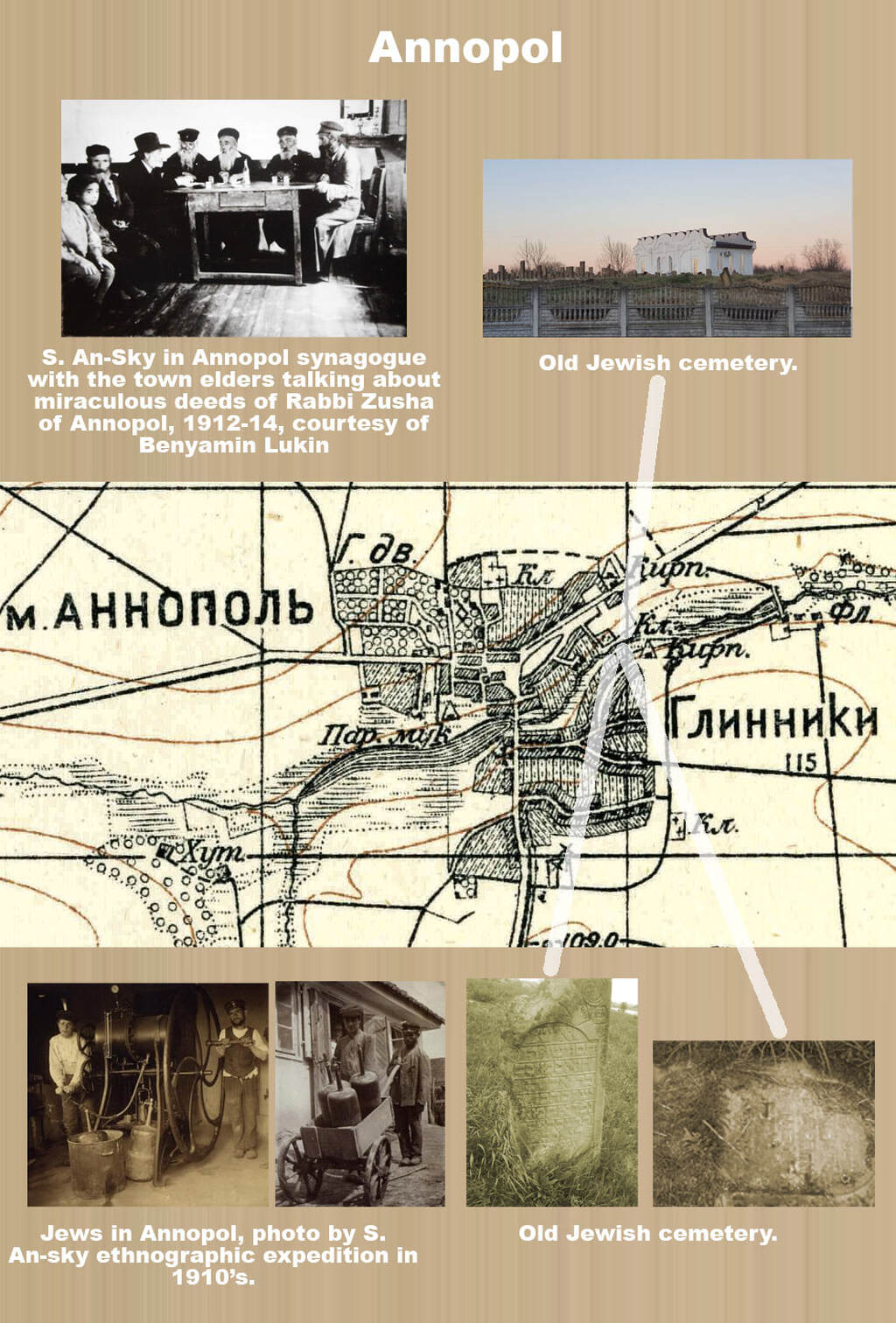

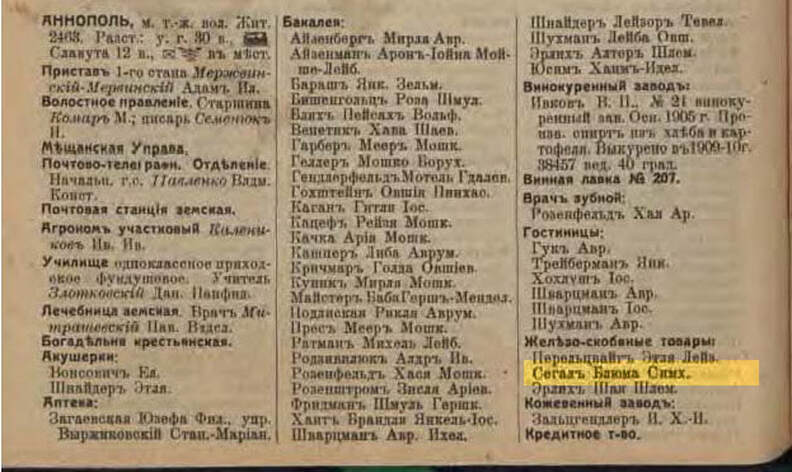

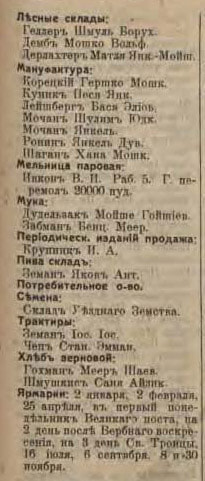

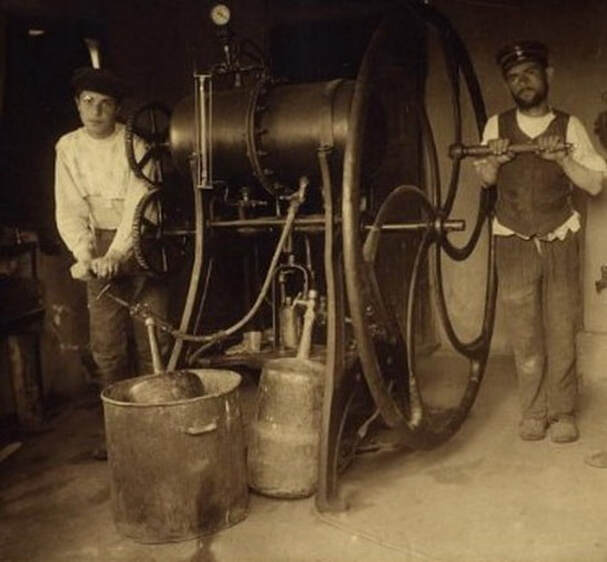

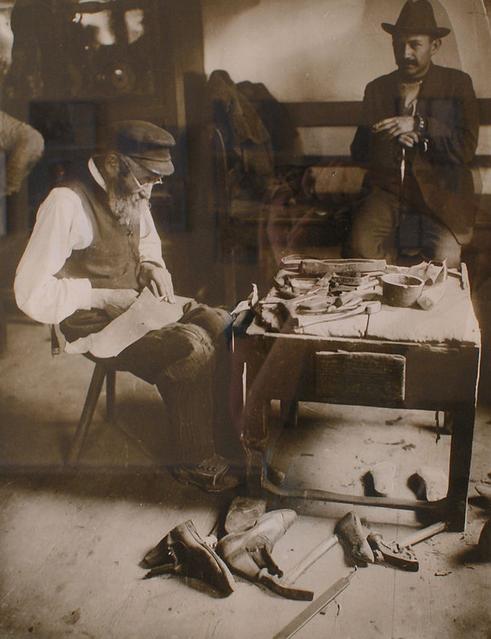

Segals from Annopol

Information from:

http://jewua.org/annopol/

ANNOPOL (before 1761 – Glinniki), a village in the Slavutsky district, Khmelnitsky region. Settlement is mentioned first time in 1602.

Since 1793 became a part of Russia. In the XIX – early XX it was a shtetl in Ostrog yezd, Volyn guberniya. In 1923-1930 Annopol was a center of a district.

Beginning

Jews settled there in the XVII century.

Since the 1770s Annopol played a prominent role in the Hasidism movement. In Annopol lived Dov-ber from Mezerich and his son Avrom “Ha-Malach” (“Angel”) (1741-1776, Fastov), who later became a Tzaddik in Fastov.

Dov Ber ruled in religious communities of Rivne and Mezhyrich, for which he received a title of Great Magid from Mezhirichi. For further spread of Hasidism to west tzadik Dov Ber chose Hannopil where lived a large Jewish community. He lived here 12 years, died and was buried in a Jewish cemetery.

In Annopol studied Schneur Zalman from Lyadi. After the death of Dov-Ber in Annopol settled his disciple and successor, Meshulam Zusya Annopolsky (? -1800), who did much to spread Hasidism in Volyn. Zusi’s son-Zvi Menachem Mendel (? -1814) was a Tzaddik in Annopol after his father’s death. In the 19th century Jews in Annopol were involved in wholesale and intermediary trade of agricultural products or were a craftsmen.

In 1845 the annual budget of Annopol Jewish community was 149 roubles. There were two synagogues (stone and wood) in 1858.

There were synagogues and an alms-house in 1890. Bund and the Zionist groups operated illegally between 1910-1916 in Annopol. On November 30, 1917 peasants who came to a fair organized a pogrom.

During the Civil War local German Vitcke organized Jewish pogrom. 8 Jews were killed. This man organized Jewish pogroms in Kilikiev, Slavuta, Berezdov and Velikiy Sknit too. These pogroms were investigated in 1937 and protocols are available in archive.

After Civil War

After WWI and the Civil War Jewish population began to decrease. Between 1920 and 1934 rabbi was Aron-Uri-Leib Klimnovich. There were 5 synagogues, four-year Yiddish school, in which children were not forced to write on Saturdays.

In May 1924 there was registered Jewish religious community, the head of community became Kogan Wolf Lvovich. The largest synagogue was brick with 8 copies of Torah.

Jewish population of Annopol:

1784 – 215 Jews

1847 – 1626 Jews

1897 – 1812 (82%)

1923 – 1008 Jews

1926 – 1278 (67,4%)

1931 – 1280 Jews

2000 – 0 Jews

In 1925 was founded the Union of Jewish craftsmen. In the middle of 1920’s among Jews in Annopol were – 175 workers, 45 employees, 123 craftsman, 232 poor peasant, 458 – peasants of average means, three affluent peasant, 22 clergymen. Members of OZET were 110 Jews. There was a Jewish library.Jewish collective farm was created in 1930.

At April 4, 1927 in Hannopol lived 1313 Jews and Poles, there were 241 Jewish households. In the same year in the 4-year Jewish school studied 102 children in 4 groups, worked two teachers.

In 1931 was created Annopol Jewish national village council. In this year Jewish population was 1280 people.

Since the beginning of collectivization in the shtetl was organized a Jewish collective farm. In 1930s there were Jewish Council, seven-year Hebrew School (closed in 1939) and Jewish Kindergarten. In 1940, in 9 grade of Hannopil School studied 43 students, only five of them were Ukrainian and Polish, the rest were Jewish children. Ukrainians, Poles and Jews lived in the shtetl in friendship and helping one another.

In 1932-1933 Annopol Jews suffered from Holodomor.

Description of pogroms in Annpol, 1919-1920:

To the Central Section for the Relief of Victims of Pogroms:

From Krupnik, a Citizen of the Town of Annopol

"From the very first day of the occupation of Ukraine by the Petlurist forces, small detachments of Petlurists began to arrive in the town of Annopol, who unmercifully looted the Jewish population, but did no killing. After one occurrence, when a Petlurist robbed a soldier who had just returned from captivity in Germany and who offered resistance, the Petlurists began beating people up, and in one day eight were killed and about sixty wounded. The wounded, afraid of being shot, did not show themselves on the street, and died for lack of treatment.

For about two months the Jews lay in cellars and bathhouses. They did not hide in synagogues, because there had been a case in which the Petlurists had plundered Jews who were hiding in a synagogue. The Jewish Community was functioning officially, but was not active, because on the first day of the arrival of the Petlurists its president, Holtzmann, was arrested and shot.

Small bands of five or ten men rode into the town, and, not finding the inhabitants, would look in cellars and in the cemetery and other places, and if they found inhabitants would take them home and demand that they show them the places where their property and money were hidden. If they were not shown and were not given money, they would kill them. Contributions were imposed almost every day. At first they would impose levies of a hundred or fifty thousand; but later, when the resources of the place ran out and many of the inhabitants had been killed, they took three thousand or even only one thousand each time. Besides money they took clothing, pillows, samovars. In a word, they robbed the town of a sum amounting to three or four millions. The dead amount to fifteen, among them a girl of sixteen, shot on the street without any reason.

The Petlurists ran around the streets shouting, “Kill the Jews, even the Jewish children.” At a meeting which took place in the town the Petlurist officers appeared and cried shame on each other because the Jews had driven them out of Berdichev. The Christian population did not move a finger to help the Jews. They took from the Jews not only money, but even fodder for the horses, and the Jews had to buy of the Christian population everything that the Petlurists needed, even tallow.

After the Peilurists left, the population looked to the bolsheviki as saviors, but were disappointed in their expectations, since the bolsheviki also made themselves felt. The units which came looted the population, and what the Petlurists didn’t take the bolshevik units took. The actions of the Taraschan regiment may serve as an example. When the Taraschan regiment was transported to Rovno, they stopped for the night in Annopol, and all night long plundered the place, so that on the next day they carried away the loot in carts.

But more than that, fifteen men of this same regiment remained as garrison. They opened the shops and scattered abroad the goods which the Petlurists had left. There was a case in which the head of the detachment imposed a levy of 15,000 rubles, of which 11,000 was paid. But in spite of the levies and improper requisitions without the issuance of revolutionary orders, nevertheless the population remained content with the bolshevist regiments, because at least they did not kill. The “Kombed” (Committee of the Poor), which was organized after the departure of the Petlurists, made every effort to aid the hundred and fifty families who had lost all. For this purpose it started a mill going, which belonged to a land-owner Ivkov, and it is distributing among the poorest population what is received for the grinding of flour. But this is a drop in the bucket. There is no clothing, and very little medical aid (there is a hospital), while in the town and the surrounding district typhus is raging, so that the situation is desperate. The Committee of the Poor also distributes salt to the population, but in very small quantities; a pound of salt costs 30 to 35 rubles and there is none to be had in town. Medicines are distributed free, but many drugs are not to be had in town. There are no longer either rich or poor, so that there are no means for furnishing medicines. The population is reckoned at 6,000, and of these 150 families are entirely without means, while the remaining six or seven hundred families are living from hand to mouth.

In attaching hereto the certificate issued by the Annopol Committee of the Poor, I beg you to grant aid in money to the extent of 500 rubles for each Jewish family, so that thereby at least for the time being the population may be relieved, until the formation in the canton of a Committee of Relief, and until the Committee of the Poor may be able to give more help. The prices in Annopol are frightful. A pound of bread costs seven or eight rubles, whereas two weeks ago it cost four rubles. Work of every sort is at a standstill, the shops are closed, so that even at seven rubles there is no bread. Therefore I, the emissary of the Committee of the Poor, beg you to supply aid for the physically and morally crushed population. For five years now, that is, since the beginning of the war, Annopol has been living on the basis of military activities, and at every change of government Annopol has borne on its shoulders all the weight of violence and destruction. Hence I beg you to hear the voice crying in the wilderness and send financial aid to the extent of 500 rubles for each family. The local Committee of the Poor will take upon itself the handling of the money and the furnishing of relief; it is acquainted with local conditions. If the section decides to grant money, I beg you to hand it over to me, personally, since money sent through various institutions is a long time in arriving.

Supplementary Report

The population was principally employed in the grain and lumber business. There are tanneries, and many workmen; it was a very wealthy town. It is proposed to use the money for the establishment of a dining-hall and hospital. The 150 families in want, mostly artisans, even if the instruments of production could be furnished them, would have no work to do and no orders. The amount requested is for first aid. Typhus is raging; there is a hospital, with inventory and list; but there are no supplies and hence it is not functioning.

http://jewua.org/annopol/

ANNOPOL (before 1761 – Glinniki), a village in the Slavutsky district, Khmelnitsky region. Settlement is mentioned first time in 1602.

Since 1793 became a part of Russia. In the XIX – early XX it was a shtetl in Ostrog yezd, Volyn guberniya. In 1923-1930 Annopol was a center of a district.

Beginning

Jews settled there in the XVII century.

Since the 1770s Annopol played a prominent role in the Hasidism movement. In Annopol lived Dov-ber from Mezerich and his son Avrom “Ha-Malach” (“Angel”) (1741-1776, Fastov), who later became a Tzaddik in Fastov.

Dov Ber ruled in religious communities of Rivne and Mezhyrich, for which he received a title of Great Magid from Mezhirichi. For further spread of Hasidism to west tzadik Dov Ber chose Hannopil where lived a large Jewish community. He lived here 12 years, died and was buried in a Jewish cemetery.

In Annopol studied Schneur Zalman from Lyadi. After the death of Dov-Ber in Annopol settled his disciple and successor, Meshulam Zusya Annopolsky (? -1800), who did much to spread Hasidism in Volyn. Zusi’s son-Zvi Menachem Mendel (? -1814) was a Tzaddik in Annopol after his father’s death. In the 19th century Jews in Annopol were involved in wholesale and intermediary trade of agricultural products or were a craftsmen.

In 1845 the annual budget of Annopol Jewish community was 149 roubles. There were two synagogues (stone and wood) in 1858.

There were synagogues and an alms-house in 1890. Bund and the Zionist groups operated illegally between 1910-1916 in Annopol. On November 30, 1917 peasants who came to a fair organized a pogrom.